Consequently, while the local Confederate militia was busy trying to conscript Henry and other young Franklin County men, Henry was busy hiding out from them in the Virginia hills. My grandfather Merl recounted stories of Henry's exploits that were shared with him by his mother, Henry's daughter, Susan Docia (Peters) Whitehead. At one point Henry and a dozen other local boys were captured after a church service at the Brick Church near Boones Mill and forced into service in a Rebel unit. The day before an impending battle Henry deserted with a large percentage of his company and returned to Franklin County. Every officer and many men of the unit were killed in the battle that followed.

At various times Henry and his friends narrowly escaped Rebel scouts, slipping out the back door as the Confederates entered the front, hiding out in a corn crib on Andrew Montgomery's farm and hunkering down in a cave and other secret hiding places in the hills. Eventually Henry and about seven of his cousins and friends (Abshire, Montgomery, Peters, Bowman and others) decided to make their way to Elkhart, Indiana where other folks of the Dunkard community had moved. They traveled at night and hid out during the day. When they reached one West Virginia town they were recognized as Virginian deserters and attacked by Confederate sympathizers. G'pa Henry, being the eldest, took the lead in their defense and was badly beaten. The party was separated but eventually found one another and continued on to Elkhart County.

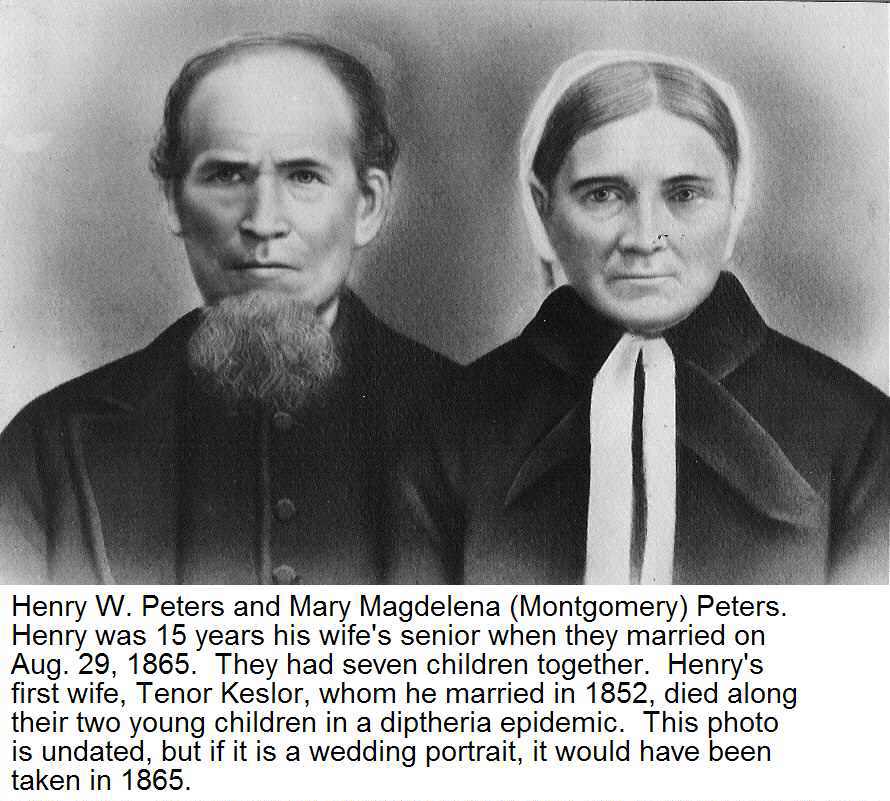

Just after the conclusion of the war thirty-seven year-old Henry married for a second time, to the twenty-two year-old daughter of his friend Andrew Montgomery, Mary Magdalena Montgomery. Henry had apparently struck up a courtship with Mary while hiding out with her brothers on their farm before fleeing for Indiana. On Apr. 9, 1865 Lee surrendered at Appamatox Courthouse. Henry wasted no time scratching gravel for home to marry his sweetheart once the war ended. He and Mary were wed on Aug. 29, 1865. But Henry liked Indiana and returned there with his new bride. They farmed and raised their seven children in Elkhart County, Indiana until his death. Mary never remarried.

Their union produced seven children including my great-grandmother, Docia, and her siblings, Janette, James Riley, Tabitha Jane, George, Ida and Daniel. My dad, who is now 87, remembers Uncle Jim and Uncle Dan, having worked on Uncle Jim's farm from time to time as a kid, during the Great Depression. G'pa Henry passed away in 1893, two years before my G'pa Merl was born.

Some people would argue that Henry and his Dunkard brothers were cowards for deserting and avoiding service. And perhaps that is true. But there is another point of view that is worthy of consideration. It is equally possible that Henry and his Brethren friends and family in Franklin County, Virginia bravely stood for what they had been taught in their homes and in their churches. While abhorring the atrocities of slavery, they also found that they must refuse to partake as the perpetrators of war. And as brave men must do, they acted upon their convictions and suffered the discomfort and indignities that came with doing so.

Consequently, while the local Confederate militia was busy trying to conscript Henry and other young Franklin County men, Henry was busy hiding out from them in the Virginia hills. My grandfather Merl recounted stories of Henry's exploits that were shared with him by his mother, Henry's daughter, Susan Docia (Peters) Whitehead. At one point Henry and a dozen other local boys were captured after a church service at the Brick Church near Boones Mill and forced into service in a Rebel unit. The day before an impending battle Henry deserted with a large percentage of his company and returned to Franklin County. Every officer and many men of the unit were killed in the battle that followed.

At various times Henry and his friends narrowly escaped Rebel scouts, slipping out the back door as the Confederates entered the front, hiding out in a corn crib on Andrew Montgomery's farm and hunkering down in a cave and other secret hiding places in the hills. Eventually Henry and about seven of his cousins and friends (Abshire, Montgomery, Peters, Bowman and others) decided to make their way to Elkhart, Indiana where other folks of the Dunkard community had moved. They traveled at night and hid out during the day. When they reached one West Virginia town they were recognized as Virginian deserters and attacked by Confederate sympathizers. G'pa Henry, being the eldest, took the lead in their defense and was badly beaten. The party was separated but eventually found one another and continued on to Elkhart County.

Just after the conclusion of the war thirty-seven year-old Henry married for a second time, to the twenty-two year-old daughter of his friend Andrew Montgomery, Mary Magdalena Montgomery. Henry had apparently struck up a courtship with Mary while hiding out with her brothers on their farm before fleeing for Indiana. On Apr. 9, 1865 Lee surrendered at Appamatox Courthouse. Henry wasted no time scratching gravel for home to marry his sweetheart once the war ended. He and Mary were wed on Aug. 29, 1865. But Henry liked Indiana and returned there with his new bride. They farmed and raised their seven children in Elkhart County, Indiana until his death. Mary never remarried.

Their union produced seven children including my great-grandmother, Docia, and her siblings, Janette, James Riley, Tabitha Jane, George, Ida and Daniel. My dad, who is now 87, remembers Uncle Jim and Uncle Dan, having worked on Uncle Jim's farm from time to time as a kid, during the Great Depression. G'pa Henry passed away in 1893, two years before my G'pa Merl was born.

Some people would argue that Henry and his Dunkard brothers were cowards for deserting and avoiding service. And perhaps that is true. But there is another point of view that is worthy of consideration. It is equally possible that Henry and his Brethren friends and family in Franklin County, Virginia bravely stood for what they had been taught in their homes and in their churches. While abhorring the atrocities of slavery, they also found that they must refuse to partake as the perpetrators of war. And as brave men must do, they acted upon their convictions and suffered the discomfort and indignities that came with doing so.

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement