Dad spoke of his Tucker relatives and the many doctors from that family (Newton G. Tucker, etc.). He loved Claudia Sainz Andrews and admired son John's brother-in-law Michael Mangan, but was unaware of doctors John Summerfield Andrews, Ephraim A. Andrews, Robert Cobb Andrews and Brockenbrough Andrews. He was proud of his heroic daughter Joan.

Dad, a gifted musician, is related to Tennessee Williams through his g-g grandmother, Lucy Lanier Andrews and through the Lanier side of the family, musicians to the Kings of France, then England and to Thomas Henry Malone founder and the first dean of the Vanderbilt Law School. He is also related to Sidney Lanier and undesirable relative John Andrews Murrell. His daughter-in-law Sue is related to Philip Arnold, son of Penelope, and John B. Slack, of diamond hoax fame.

Daddy's closest cousin, maybe even closer than Paul Harris, was Orlando Simpson. Dad said, "Orlando, Jr. ran the farm. He was my hero." Son David: "Funny, thinking back on those trips to Fairfield, IL. Orlando and his family clearly loved Daddy, and me by extension. It's only now that I see the smiles and attention so clearly as more than the kind of bounded affection we experienced with Aunt Sara and Grandmother, and even with Auntie Joan, maybe. Of course it was just a couple visits, but I remember very clearly being nonplused and unable to recognize the way all that family came to see Daddy and me, and with such interest. I spent more time with Larry. He may not have taught me to fish, but I'm pretty sure it was with him on his farm pond that I caught my first fish. I remember being incredible with excitement and didn't want to leave. I loved Larry, and he seemed especially genuine to me and willing to please a young kid--for a young teenager or in his early 20s."

At Hume Fogg HS, Dad was Vice-President of the Astronomy Club in which Dinah Shore was a member.

Father's legacy: A Love of nature and virtue

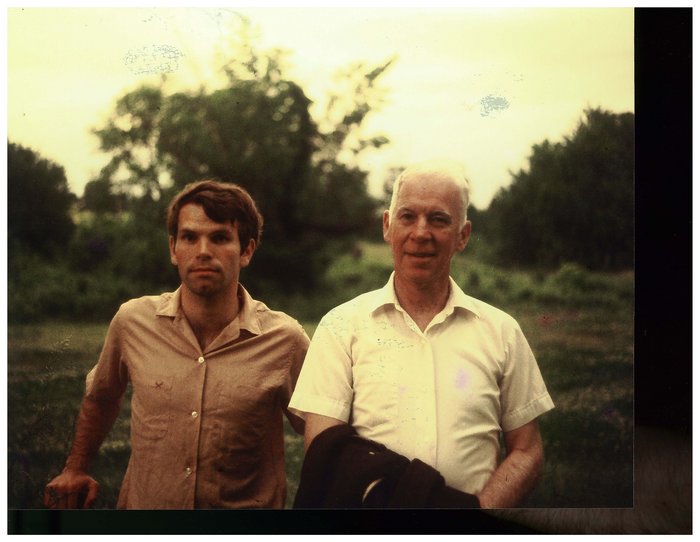

When my 88-year-old father died early last month, the event was not unexpected. A mild stroke last summer was followed this May by one more debilitating. By the standards of the departure, it was a peaceful passing -- on the Lewisburg family farm and in the company of loved ones.

Understanding that the end was near, most of my siblings came home to Lewisburg to be with our father in his last weeks, taking shifts to help our mother with Dad's needs and to assist the medical personnel who made periodic visits. My watch was generally in the early morning hours until sunrise when the atmosphere was peaceful and quiet.

I was there to talk to him, adjust his position and monitor his respiration and IV. When sunlight broke over the horizon each morning, we could see through his window the promise of a new day. In the rising mist deer and horses foraged on wet orchard grass, a pair of gray foxes cut through the field from their eastern lair to some breakfast in the west, and a cacophony of bird sounds filtered into the house.

Dad loved nature. On more than one occasion he told me that, though truth can be divined from sacred scripture, God's greatest revelations come from nature because "that text is written in His own hand." This affection for the beauty and mystery of natural life made him appreciate the natural sciences because they attempted to quantify the cosmos, the Romantic poets because they glorified nature, and the American transcendentalists because they linked the life of the mind to the lessons learned from the symmetry, design and immutable constancy of nature's laws.

One of his favorite writers was Ralph Waldo Emerson, the transcendental essayist whom Dad discovered while a student at Vanderbilt and who prompted in him a rather passionate and youthful flirtation with Unitarianism.

Dad was also fond of saying that honorable behavior in life was more valuable if it came from a love of virtue for its own sake than from a fear of hell. He admitted to me on numerous occasions that he had problems with the notion of hell. Ultimately he converted to Catholicism, but I am not at all sure whether he did it out of conviction or to please my mother. Knowing Dad, it was probably both. He was good at reconciling positions that others found irreconcilable.

My father was also something of a determinist. In one memorable conversation I had with him while looking for prehistoric flints in our Arrowhead Field, he said that he had the free will to buy an ice cream cone at Alford's Drug Store whenever he got the urge. But he couldn't explain why he liked chocolate over vanilla. He continued by admitting that he could not determine his IQ, his parents, his race or the epoch of his existence. Similarly, he felt that religious faith was not always an act of the will.

From my teenage years well into middle age, Dad would periodically give me a copy of John Cardinal Newman's 1852 tract "The Definition of a Gentleman," a beautiful piece of prose that perhaps is better suited to a less cynical age when thoughtful optimists genuinely believed in human perfectibility and in the efficacy of noblesse oblige.

A gentleman is tender towards the bashful, gentle toward the distant, and merciful towards the absurd. He is seldom prominent in conversation and never wearisome. He makes light of favors while he does them, and seems to be receiving when he is conferring...He submits to pain because it is inevitable, to bereavement because it is irreparable, and to death because it is his destiny."

Unknown to me before the family gathering for the funeral, Dad also gave copies of the Newman lecture to my brothers when they were ready for college and, more recently, to my three sons. This came as something of a shock to me because I always regarded myself, after my mother, as Dad's closest confidant. I thought myself the only recipient. If there was a needling suspicion that his handouts were to mitigate some disappointment in me, I am now reassured because, in all honesty, I regard my brothers and my sons as conspicuously more virtuous than I--and they got the handouts, too. It was not in Dad's nature to be judgmental.

Grief is very personal, and, as each of us dies individually, so too do we grieve. Between Dad's death and burial, I was too busy to grieve. My eyes were dry when I hoisted the gurney into the ambulance when death was pronounced. Likewise, I held it together at the cemetery during the 21-gun salute, the very moving rendition of taps by a Guard bugler and the presentation of the folded flag (Dad and Mom were both World War II officers). After the luncheon-reception at the Lewisburg church, I returned to Columbia with Claudia.

However, too much was left unsaid, the prayers were all too public and the fatigue from three weeks of little sleep was numbing. I decided to return to the cemetery for some private moments.

It was late in the afternoon when I arrived at the Andrews-Liggett Cemetery. No one was present. The sun had returned after a brief lightning storm during the internment and the heat and humidity were intense. At the grave, two things happened that were totally unanticipated.

First, as I looked down at the fresh dirt and read the headstone, the floodgates opened and I wept as I have not wept since I was a child. It was all too sad. It wasn't long before I regained my composure by saying some prayers and reciting a rosary.

Then, noticing that the four largest flower arrangements were somewhat distant, I decided to move them closer to the fresh dirt. My shirt was soaked from that labor. Then, before departing, I spoke audibly to my father. I told him that I hoped he was alright, that he was at peace, and that he was in heaven. I also remember saying that I wished there were some way I could know for sure that everything was alright.

At that precise moment, a breeze blew across the cemetery from the west and a dark red rose fell from the flower arrangement on the right of the headstone. I was about to return the flower to its stand when I noticed that a ribbon from the arrangement read "From Your Children." It was all over with that single gust of wind.

Yes, it may have been coincidence. In the process of dragging the stand to its new location, I may have disturbed the flower's footing. However, in the grand scheme of things, I prefer to believe that Dad was reassuring me that all was as it should be.

Bill Andrews is Chairman of the History Department at Columbia State.

LEWISBURG TRIBUNE- 6/2/2005

William L. Andrews, 88 years, died of heart failure peacefully at his home Thursday at 1:30 am on June 2, 2005. A World War II veteran, an attorney, an educator and a farmer, he regarded his greatest accomplishment being a father. His best times were those years spent with his wife of sixty years and his six children on the Lewisburg family farm he inherited from his parents: William L. and Stella Simpson Andrews.

In his last year of law school at Vanderbilt, he was conscripted in the first peacetime draft in U.S. history and served for five-and-one-half years.

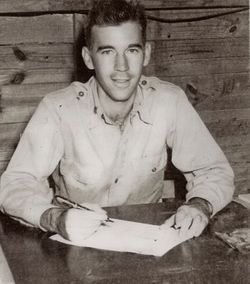

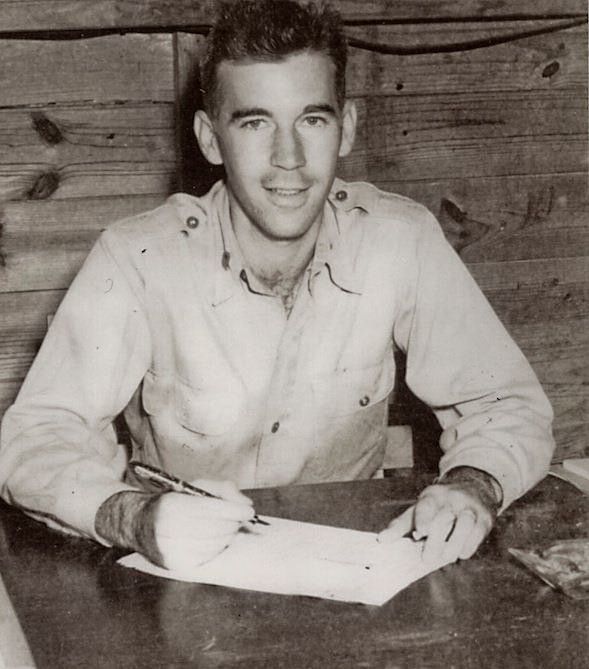

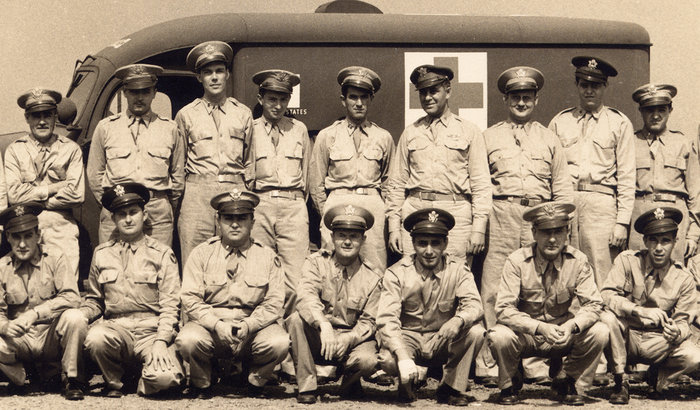

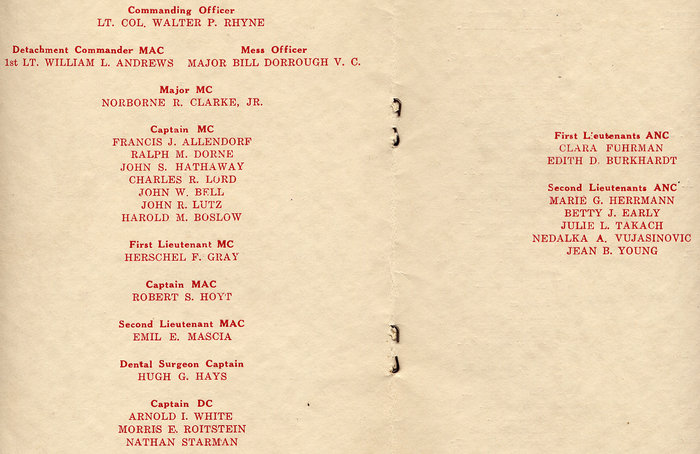

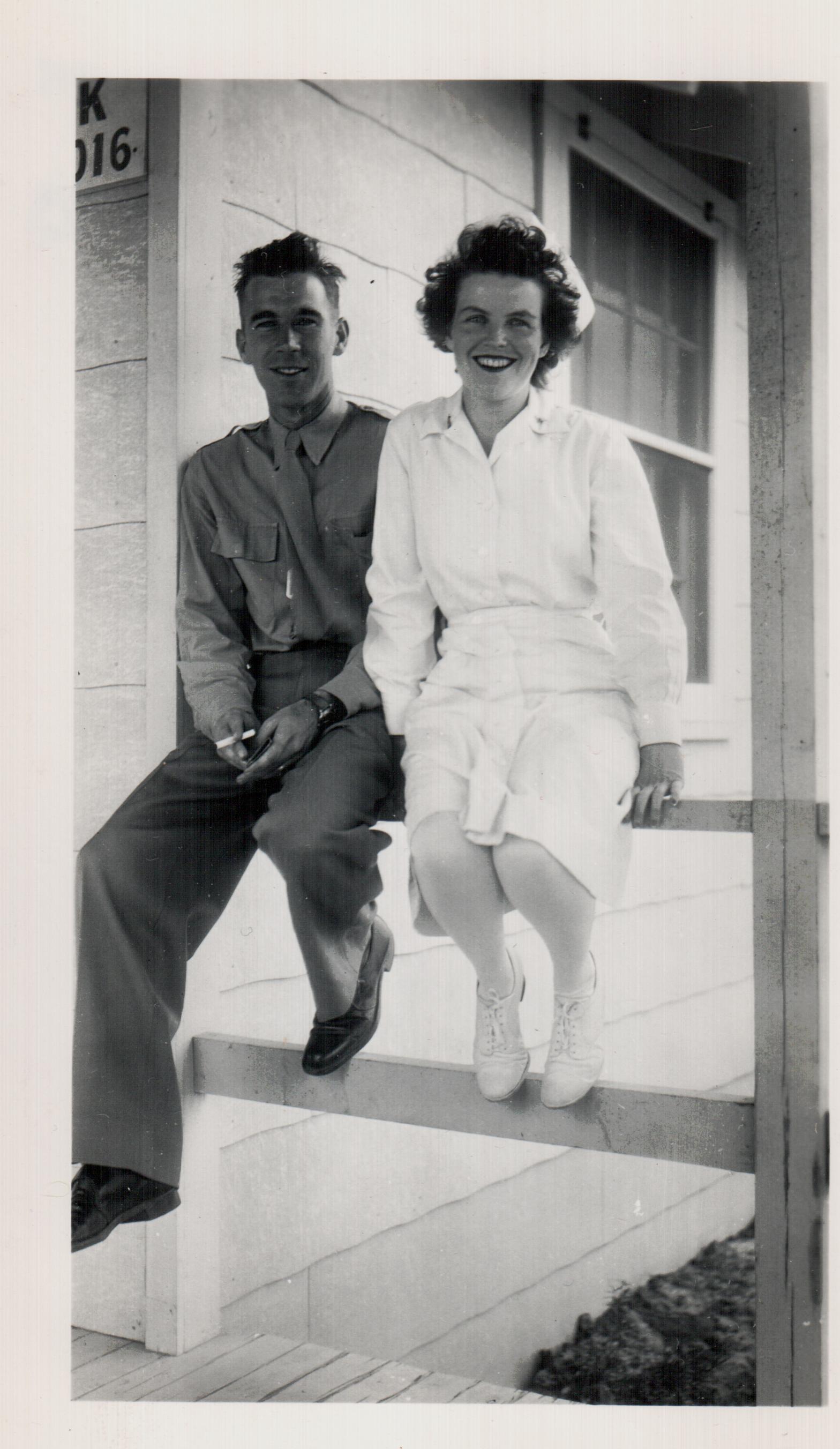

It was as an officer in the army medical corps at Stuttgart Army Airfield that he met and married Elizabeth Early, head surgical nurse at the base hospital. They both received the American Campaign Medal for service to their country in the Second World War.

After receiving his law degree, he and his wife moved to their 236 acre farm on the outskirts of Lewisburg where they raised their children. Mr. Andrews supplemented his farm income with a career in education as a teacher and principal. After retiring, he changed the farm operation from dairy to beef cattle.

A communicant at St. John's Catholic Church, he was the organist for forty years. In a recent salute to him by the local Knights of Columbus, he was described as a man "beloved by his life-long friends at St. John's and by all who know his soft-spoken manner and kindness. Very endearing is his love of people and his touch of shyness." Ever the educator, he gave to his sons for their instruction copies of his favorite essay by John Cardinal Newman - "The Definition of a Gentleman." All of his children regard the passages of this tract emblematic of their father's personality and values. They consider its words a fitting epitaph for a true Southern gentleman:(see quote above).

Mr. Andrews is survived by his wife Elizabeth, children William X. (Claudia Sainz) Andrews of Columbia, John Early (Sue Sullivan) Andrews of Colora, MD, David Edward Early (Judith Condon) Andrews of Chattanooga, Joan Andrews (Chris) Bell of Montague, New Jersey, Susan Andrews (Dave) Brindle of Lewisburg, and Miriam Andrews (John) Lademan of Annapolis, MD, and thirty-eight grandchildren.

A requiem mass was concelebrated by Rev. Thomas Perrin, pastor of St. John's, and Rev. Zacharias Payikat of Karala, India, at St. John's Catholic Church in Lewisburg at 11:00 am on Monday, June 6th. Burial followed in the Andrews-Liggett Cemetery with full military honors.Pallbearers were grandsons: Matthew, Will and Glennon Andrews, Joseph Andrews, and Andrew, Daniel, Michael, and Joey Brindle.

HIS SISTER SARA TALKING ABOUT HER BROTHER:

My brother growing up always had the best disposition. We were all very close together. I saw somebody Sunday and he said "Sara, I haven't seen you for years, but he has. And he said, "how's Willy?" Everybody called him Willy, the boys here that knew him. He said, "every time I go by Oakland, I say to this friend who's with me, "that's where Willy lived." Yes, my brother was a good student. He went to Lewisburg, I don't think he ever went to a public school; he went to a private school, Price-Webb, and I did too. I was quite a bit older and I had two or three years in the public school. And after my father died, he was eight and I was sixteen, we moved to Pulaski which was close by, and I went to high school there and he went to the grade school there and it was right after my father died and we were all sad, but we had more friends there and I run into them all the time now.

DAUGHTER JOAN:

My early memories of my brothers are wanting to be like them and play with them. I remember Bill as more the storyteller. I would say "bad boy" to Bill if he did anything. I remember Lake House and feeling that if wanting to go outside, John would go out with me when Bill and Susan wouldn't. John doing things like that more than the other kids.

DAUGHTER JOAN'S MEMORIES

I remember Daddy walking with us a lot in the woods and telling us stories. Daddy was sweet and quiet. He spanked me twice, once after we took corncobs out of John Ezel's old house in woods. I remember John getting in trouble with Daddy a lot, because he got the tractor stuck in the mud or because of electronics. I remember once John getting spanked and running into woods. I remember when Joel died. John and I planted cedar trees on either side of tomb near the clay pond. I remember Mama always singing to us, saying rosary with us and Mama saying that John was the only one who stayed awake for the entire rosary each night. I remember times when Mama would cry. I recall staying at Grandmother's and Aunt Sara's for two weeks while Mama was in Europe with Ganger and Aunt Sara holding up a newspaper article showing an oceanliner sinking while at sea saying that your mother was on that ship and she's dead. I remember trying to convince Susan that Aunt Sara was lying and running away with Susan that night.

"THE ARROWHEAD FIELD" BY SON BILL:

My favorite scene in the movie "Forrest Gump" is the soliloquy in which the protagonist, played by Tom Hanks, stands by the grave of his love, musing about fate and chance in life's dramas. He tells the recently departed Jenny that, while Lt. Dan believes in destiny, his mother believes in the random thunderbolts of chance, an existentialist's universe as unfathomable as a box of chocolates. And then he concedes that perhaps they are both right, that life is a mix of determinism and chance.

I thought it a profound statement and it reminded me of something my dad once said in the Arrowhead Field. We were canvassing the furrows of the recently disked field. I remember telling him that I felt lucky that morning because I had already found three broken or badly chipped flints and that the fourth find was nearly always a perfect stone. The word "lucky" elicited from him a bemused expression, similar to what he looked like before challenging John or me to a game of chess. He said he didn't believe in luck, that determinism best defined our lives. If I had the free will to spend hours each late spring day looking for arrowheads, he opined, then there was only the probability that I would find something over time. I had no control over the important things that influenced me–my family, my ethnicity, my intelligence quotient, my personality, my sex, or the epoch of my existence. He conceded that he could choose to buy ice cream at Alford's soda fountain on the Lewisburg Square whenever he had the urge but he had no choice in his preference for chocolate over vanilla.

Now four decades later I can't explain why I like Samoans over Thin Mints, tennis over golf, CNN over Fox, Spain over Germany, or Rock & Roll over Country. Like many ideas that have germinated in my mind over the years, I can trace the origins of this and other musings to conversations I had in the arrowhead field as a youngster. Many were with Dad. Many were with my siblings. The Arrowhead Field for me was a classroom. It was the education Jean Jacques Rousseau prescribed in Emile, learning from the observations of nature and asking the questions that spontaneously spring to mind from such contact with the physical world.

If our drives are forged in the crucible of genetic engines churning neurons into thoughts, then my fashioning has been fortuitous. For an overly protected child raised in the cacoon of rural Middle Tennessee in the bland 1950's, many of my little adventures of imagination have morphed into some of action. If as a child in Michigan I felt in sync with neighborhood peers, this was certainly not the case when we moved to Tennessee. There was culture shock. However, children can often adapt more readily than adults. It was easier for us kids than for Mom. We were now being raised as a family of Catholics in the WASP landscape of rural Middle Tennessee. Born in Detroit, I was the Yankee sibling. Our family didn't fit the mold. Dad received his law degree when I was a year old, his schooling interrupted by the war. He and my Mom were raising a brew of children in the protective sanctuary of a 236-acre farm. We lived simply. Dad gave up law for a profession less lucrative financially but, as he confides, more rewarding emotionally. He became a public school teacher and principal.

We lived a little like innocent hobbits on our farm, close to the earth, living simply, and robustly incubated. We drank milk so fresh from the cows that it arrived warm, Mom spoon-scooping off the creamy surface froth. When the cows foraged on onions, we could taste the bitter flavor in the milk. We swam in the Clay Pond, ate watermelons at the Spring, and climbed trees to such heights that we confirmed the spherical form of the earth. We raced horses bareback and hunted arrowheads barefoot. And because Mom wanted us educated as Catholics, Dad drove nearly forty miles daily so we could attend parochial school. Mom made sacrifices for our religious training and Dad made sacrifices to please Mom and to keep the family intact after years of religious strife.

The lives of all my siblings – John, Joan, Susan, David and Miriam – appear to alternate between adventure and discord. If these lives seem ordinary to some, to my biased mind they resonate with drama, adventure and not a little altruism. This appreciation I have not always had. As a child, lying down at night in the soft tilled earth of the Arrowhead Field under a canopy of a billion galaxies, I sensed our unimportance. However, when I reminisce with family members in an environment of frankness and candor, I am always stunned by the variety and depth of our collective and individual experiences, adventures that in no way appear ordinary.

My little adventures often came my way unsolicited, germinating in some culture-bed unknown to me. Collectively, I suppose, they acquired sufficient critical mass to register as worthy of note and friends keep urging me to write about them...I've hiked the Appalachian trail and regard it less an epiphany of sudden self-awareness than as a monumentally humdrum enterprise. Unlike Bryson, I celebrate my casual encounters with black bears. Perhaps my dismissive attitude toward the Bryson saunter is more the result of having been raised on a farm where we rode horses, climbed trees, shot guns, camped in musty-aromatic WWII pup tents, stepped on snakes, and encountered wildlife as a matter of course. These were rights of passage for my siblings and me. We were aware that we were transfiguring the landscape with our small feet, leaving footprints as indelibly recorded in memory as 200 million year old dinosaur tracks imbedded in fossil-encrusted magma.

Our little adventures of childhood have evolved into the adventures of adulthood. The recollections are burned into memory because they engaged all the senses. I've watched weaving streams of red ribbons emerge from hovering helicopter gunship in the night skies of Vietnam, the visual splendor enhanced by the smell of cordite, the shattering sounds of exploding ordnance, and the spasmodic whiffs of balmy breezes rushing wave-like upon us. On occasion when tribal yearning trumped discretion, I sprinted down Pamplona's Calle de San Jose, courage-fortified by the consumption of cheap Navarese wine, running in lock-step with a mass of red-bereted humanity before stampeding Andalucian bulls. I've climbed majestic peaks on four continents and looked down to see pretty much the same people at each base, all enjoying the same 99.9 percent of genetic makeup. I've camped in the moon shadows of Stonehenge and Avesberry, inspired by the former and terrified by the latter. I once followed an Afghan camel caravan of Pushtan nomads journeying to Hazarrastan and filmed Tajiik horsemen fighting for possession of a headless goat carcass. I've exchanged trade goods with the Lacondones of Chiapas and the descendants of the Inca in the Andes. I worked for the presidential candidacy of Eugene McCarthy and I attended the burial of his primary rival, Bobby Kennedy. In Morocco I was stoned by a coterie of angst-laden men for photographing a local woman without a chador and in Afghanistan for photographing the grave of some revered mullah.

On a train in Eastern Turkey I fought four local men who were assaulting an American girl and I prevailed because my cleated jungle boots better negotiated the frozen urine on the floor. I slept one night in the crest-comb vault of Tikal's Giant Jaguar Temple Number One, sharing my lodgings with howler monkeys who in manic chatter implored me to abandon my perch. Once in a violent lightning storm in the tropics of South America, I wrestled a massive boar hog for possession of a generator shed hoping to save a patient in surgery. In an adrenaline surge in my pre-pubertal youth, I swung with my siblings Frost-like in broad elliptical arches from young maples. I spent entire summers looking for atlantl points in the Arrowhead Field and years daydreaming about the affections of flirtatious women.

When friends were about to consign me to a jaded life of cynical self-absorption, an idealistic young doctor whose dream was to work among the Third World poor saved me. When attending the birth of my three sons, I acquired a renewed sense of the miraculous which skepticism and science have occasionally taken from me...I've gazed through frosty windowpanes upon the tire fires of Canadian ice fishermen and I've listened mesmerized to the plain chant of Benedictine monks in a millennium-old French cloister. With bare feet I've stomped grapes in Bordeaux for hourly wages and with blistered hands I've loaded produce as a day laborer in Barcelona. I once observed an exorcism in a tropical South American hamlet and conversed with an old Yucatani Maya priestess who chanted incantations for rain. In Ireland I kissed the Blarney Stone and in the dark reliquary of an Italian catacomb I stumbled upon the desiccated bones of Christian martyrs. As a child I was mesmerized by the pathos of Ann Frank and the altruism of Atticus Finch. In college the buzz came from the existentialism of Unamuno and the descriptive power of Dostoyevsky. I've section-hiked the Appalachian Trail, canoed stretches of the Lewis and Clark route, and ridden my horse through all the national forests along Hernando de Soto's 16th century odyssey. I've been frisked at gunpoint at so many Latin American roadblocks that the experience no longer elicits concern and I've flown on so many obsolete third-world aircraft that I constantly make little promises to God, promises that, with feet on the ground, I conveniently forget. I was interrogated by Afghan intelligence officers who thought me an American spy and I was examined for contraband by a burka-ensconced Iranian hag who held her hand to my heart. I've spent almost as much time playing tennis as looking for arrowheads and I have some small trophies to validate the bragging rights when I'm in the mood for arrogance.

People at home and abroad have extended me so many courtesies and favors that I could never repay their generosities in a single lifetime. I've been to places that challenge the notion that we were created in God's image and I've met people whose lives are monumental testaments to a divine spark within. By walking across a hundred battlefields, I have come to know that humanity loves war and that, in the divine schemata of evolution, we have as a species a long way to go before we behave as we were enjoined in the Sermon on the Mount.

If friends have succeeded in having me write about my small adventures, I'm realistic enough to know they pale in comparison to the life tales of many casual acquaintances about whom I write in this story. The experiences highlighted in this book should reaffirm for the discerning that it is not adventure and it is not wealth that give meaning to our lives. Life is a priori a gift and it is well lived if in the final account it is defined by the Stoics injunction to love family, defend friends, aspire to truth, show compassion, find joy in work, and make good one's allotted time in this world. The sublime truth of the matter is that our tenure here is brief and precarious.

THE ARROWHEAD FIELD CHAPTER ONE - ANTECEDENTS: Grandparents, German POW's and Turtle Eggs

I found my first arrowhead in the spring of 1954, less than a year after our return to Tennessee. I remember the event well not only because it began my obsession with collecting prehistoric projectile points but because it was sandwiched between other events which, if I didn't have the capacity to appreciate them at the time, were important to the history of my family.

That week Dad was glued to the television set watching Senator Joseph McCarthy haranguing the US army for its alleged links to communist cells in the Signal Corps. Although I've often witnessed emotion in my dad, I've seldom seen the kind of affective distain he reserved for McCarthy. Dad regarded the Wisconsin Republican as a self-promoting, headline-grabbing demagogue whose shoddy investigations were matched by what Dad regarded as a dangerous disregard for constitutional rights. Dad was still a liberal back in those days, not yet jettisoning his high enthusiasm for New Deal activism or the crusading idealism of his student days at Vanderbilt University.

Mom was in Europe at the time. She and my grandmother had left the week before on the Queen Mary to tour Europe and, the highlight for her, to have an audience with the Pope. The occasion was the canonization of Pope Pius X. My parents could not have been more different where religion was concerned. Dad is a native Tennessean who was raised Methodist but who discovered Emersonian transcendentalism in college and, to this day, carries on a lively flirtation with the Unitarian take on the world. My mother is a devout Irish Catholic of the pre-Vatican II school, believing in the efficacy of Lourdes water, festooning the old farmhouse walls with reproduced Renaissance iconography of Jesus and Mary, and lamenting the absence of a resident priest in Lewisburg so she can attend daily mass.

In fact, it was primarily the religious conflict between them that occasioned my parents' two-year separation and it was Dad's willingness to tactfully live with what he regarded as Mom's religious eccentricities that led to their reconciliation. It is one of the curious ironies in my family's life that Dad attends Sunday mass with Mom while my mother proudly considers him a convert to the faith, ignoring the fact that he has yet to embrace wholeheartedly the idea of Christ's divinity. To see them today holding hands and laughing together through sixty years of marriage is somewhat miraculous in itself. As the oldest of six children, I am the only one who can remember the traumatic and contentious early years when my parents fought their religious wars without taking prisoners.

Dad was born in 1916 to William Lafayette Andrews, Sr. and Stella Simpson in the small rural town of Lewisburg, about fifty miles south of Nashville. Named after his father, Dad was southern to the core, educated in private schools and raised under a chivalric ethic that esteemed civility and courteousness, reserve and restraint. By the time of my father's birth, Grandfather Andrews, a graduate of Macon Business College, was already a prominent entrepreneur who owned two general stores. Soon he would open a bank and buy up prime real estate on the Lewisburg Square. He was a hardworking, fastidious and socially conservative teetotaler who died in 1924 in his early forties. No one knows for sure the cause of death but his extremely jaundiced appearance during his last days suggests a form of hepatitis. Dad lost his father at the tender age of eight and was raised thereafter by his mother and a sister, my Aunt Sara, who was eight years his senior. More so than my Dad, it was Aunt Sara who acquired my grandfather's conspicuous talent for moneymaking through scrupulous frugality. Two years ago, Aunt Sara died, one month shy of ninety-four. To the end she reminisced about her wealthy friends in the Junior League and the prominent social elites of Nashville with whom she associated as a young woman in the twenties.

Left with a small fortune in savings and investments, my widowed paternal grandmother abandoned the small town of Lewisburg and moved to Nashville with her two children whom she enrolled in private schools. Aunt Sara graduated from Belmont Methodist College and later headed the children's section of the Nashville Public Library, a position she retained until retirement in 1973.

As a child, my father attended Duncan Latin Grammar School and Hume-Fogg in Nashville. In high school at Hume-Fogg, Dad's favorite course was an astronomy class in which the teacher encouraged the students to make their own reflector telescope. His instrument had a 6-inch mirror with lenses sufficiently powerful to reveal the rings of Saturn. His first year in college was at Davidson in North Carolina where the highlight of his spring semester was a trip he took with a friend hitch-hiking to South Carolina. There he met an old African-American woman who proudly informed him that, when she was a young girl, she stood in a crowd of people listening to a speech given by John C. Calhoun, the great southern fire-eating apologist for slavery whose stand on states rights portended secession and Civil War. In his sophomore year, Dad returned to Nashville where he attended Vanderbilt University. There he could often be found on the campus tennis courts where he brandished a Write-Didson racquet and sported a wicked backhand. Although much of his social life centered on his Vanderbilt fraternity, Sigma Nu, he took his studies seriously and reaped the rewards in stellar grades. In 1938, toward the end of the Great Depression, he entered Vanderbilt Law School where he displayed enthusiasm for FDR's New Deal programs and sympathized with the Loyalist cause in the Spanish Civil War. The world of the Andrews was thoroughly WASP and they moved in a social milieu that would have appeared alien to my mother.

Where my dad is laid back and soft spoken, Mom is a firecracker, a body constantly in motion whose outspoken candor and hardheadedness are perceived by many southerners as emblematic of Yankee assertiveness. She too came from a conservative background. She was the daughter of Edward J. Early and Jessica A. O'Keefe, themselves both grandchildren of Irish immigrants who settled in Wisconsin. To us children, they were Gampa and Ganger. Gampa was born in 1885, the son of John J. Early, and graduated with a civil engineering degree from Marquette University around 1907. One of his sisters [Ella] became a nun and the other [Margaret], a missionary nurse living in China, survived a grueling four years in a Japanese prison during the Second World War.

Mom's mother, Ganger, was the daughter of Patrick Joseph O'keefe, a physician who graduated from Montreal's McGill University Medical School and set up practice in the small Wisconsin lumber town of Oconto. Ganger was teaching at St. Joseph Academy, a girls finishing school in Green Bay, when she met my grandfather. There must have been in those days a social pecking order and some latent class-consciousness among the late 19th century immigrants from Erin because the O'Keefes regarded themselves as "lace-curtain" Irish and the Earlys as "shanty" Irish. Gampa and Ganger married in their late twenties and raised three children into adulthood. Their first child died when he was two weeks old from a pneumonia picked up in the Green Bay hospital at the time of his birth. My Uncle Ted was born in 1916, the year before the United States entered the Great War. In 1918 Gampa was serving in France as a captain in army ordnance when Ganger gave birth to my mother, Betty Jane Early. Mom was born in Washington DC, during the opening phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive that ended the Great War. Reunited at war's end and anticipating economic opportunities in the bourgeoning automobile Mecca of southeast Michigan, Gampa and Ganger moved their young family from Green Bay to Detroit. Two years later their third surviving child, my Aunt Joan, was born. There my grandfather founded the Michigan Drilling Company, an engineering firm that drilled and analyzed core soil samples to determine foundation strengths for the skyscrapers being built during the boom years of the Roaring Twenties. Gampa's rigorous work ethic built wealth for his family and his savvy investment sense spared him the great economic losses visited on so many other families during the depression.

During the late 1930's, Uncle Ted and Mom attended the University of Detroit, a Jesuit institution similar to Gampa's alma mater. Uncle Ted followed in Gampa's engineering footsteps and Mom majored in the liberal arts as had her mother. Although later there was some embarrassment in the revelation, it appears that Uncle Ted during his college days was something of a supporter of the controversial Father Charles Coughlin who, like Huey Long and Francis Townsend, helped organize the Union Party which threatened Roosevelt's New Deal agenda... Mom was enjoying an active social life at U of D where she was a popular coed, a class officer, and a sorority sister in --- ---. Twice her peers elected her Snowball Queen for the university's biggest social gala. In old black and white photos and newspaper clippings collected by Ganger, Mom is always shown with a coterie of young men flocking about. In these time-capsule portraitures, she reminds me of Vivian Leigh's rendition of Scarlett O'Hara in the opening scenes of Gone with the Wind, with potential beaus flittering around her, solicitous to the point of sycophancy. One of Mom's beaus was Otto Winzen, an anti-Nazi German student who remained in the United States during the war, became an American citizen, and later gained renown as the inventor of high altitude balloons for scientific exploration of the ionosphere.

In September of 1939 when World War II erupted in Europe, Mom was enjoying an active social life at UD and Dad was in law school at Vanderbilt. A year later, as part of a preparedness program, Franklin Roosevelt inaugurated the first peacetime draft in American History and Dad was the first young man conscripted from Vanderbilt. The army permitted him to finish out the academic year before entering military service. He was one year shy of finishing law school when he entered the army.

Unlike many of their generation, neither of my parents was much affected in the quality of their lives by the Great Depression. It was Pearl Harbor that transformed frivolous and carefree youngsters into serious and responsible adults. Uncle Ted, Mom's brother, joined the Army Air Corps and after training piloted a B-24 Mitchell bomber in the European Theatre. He fell for an English girl, Katherine Thomas, and named his plane "Kate." Eventually he married her and brought her back to Detroit where my grandmother, long an aficionada of English manners and customs, treated her like royalty. Mom dropped out of the University of Detroit at the end of the spring semester in 1942 and entered St. Joseph Hospital's nursing school where enrollment soared due to the war's demand for medical personnel. She was recruited by the army at her graduation in the summer of 1943 and began basic training at Montgomery Field in Alabama in January of 1944. Her first duty assignment in March of 1944 was to the main hospital at Stutgartt Army Air Corps Base in Arkansas' rice and duck hunting country.

The 1940 draft that snared my dad was the first peacetime draft in the nation's history. It was a war preparation measure because things looked so bleak for England. The Battle of Britain was not going well and England was running out of funds to pay for the Cash and Carry provisions of the 1939 US Neutrality Act. At the time Dad got his draft notice, Roosevelt was running for an unprecedented third term on a platform that called for loaning England our planes and tanks. To promote his Lend-Lease program, Roosevelt used the example of the neighbor asking to use the fire hose. Dad was inducted into the army on 16 July 1941, one year shy of graduating from law school and five months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

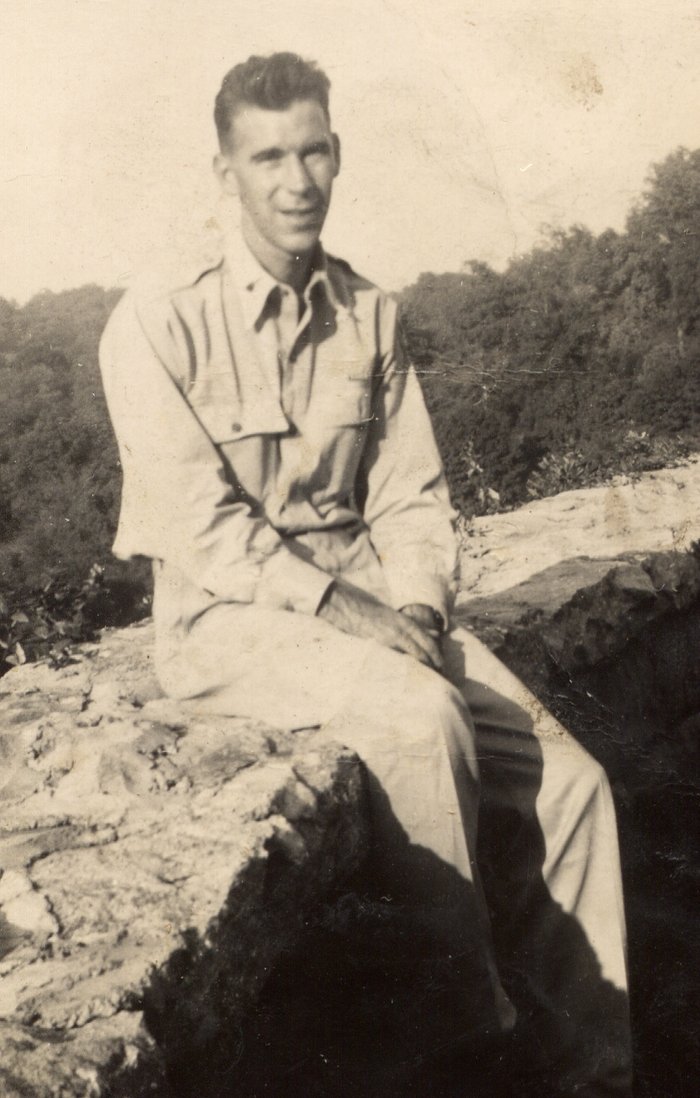

Mom was still a college student in Detroit when Dad entered the service. He received his basic training at Camp Lee, Virginia, and advanced training at Camp Barkley near the Texas town of Abilene. In mid 1942 he was sent to Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania for Officer Candidate School where he received his commission as an officer in medical administration. After a brief stint at the military hospital in Columbus, Ohio, Dad was transferred to Stuttgart Army Airfield in Arkansas where he spent most of the remainder of the war. However, in late 1943 he applied to aviation school and was sent on temporary duty to an airfield near the Davis Mountains of southern Texas to learn to pilot an aircraft. He trained in an old Fairchild biplane and was already flying solo when he experienced a near collision one day. The incident occurred when he was on a flight with an instructor whose job it was to certify him. Dad was in the front seat of the cockpit when he saw an approaching aircraft ahead of him. In the confusing sounds of rushing winds swirling around the open cockpit, the instructor yelled or signaled to Dad in a way to suggest that he was taking the controls. Apparently the teacher didn't see the plane and thought Dad had the controls. It was a near miss and such a traumatic moment for Dad that he washed out and, to this day, flies infrequently. In fact, over the past sixty-two years, Dad has only flown three times as a passenger on a commercial aircraft and then only with white knuckles gripping the armrest. I find it interesting to speculate that if my father had not washed out in February of 1944, he never would have returned to Stuttgart to meet my mother and to father the child who would be I.

Back in Arkansas doing medical administrative work, he was called upon once to assist in a special court martial case where he had to work as an assistant defense council for a homesick soldier who had gotten drunk and stolen a plane for a flight home. Although not a pilot, the young man took the plane up and actually manage to land it without much damage. It was a cut and dried case with a sentence of about six months in the brig. Because Dad was within a year of graduating from law school, officers in the judge advocate division prevailed upon him to help in the case.

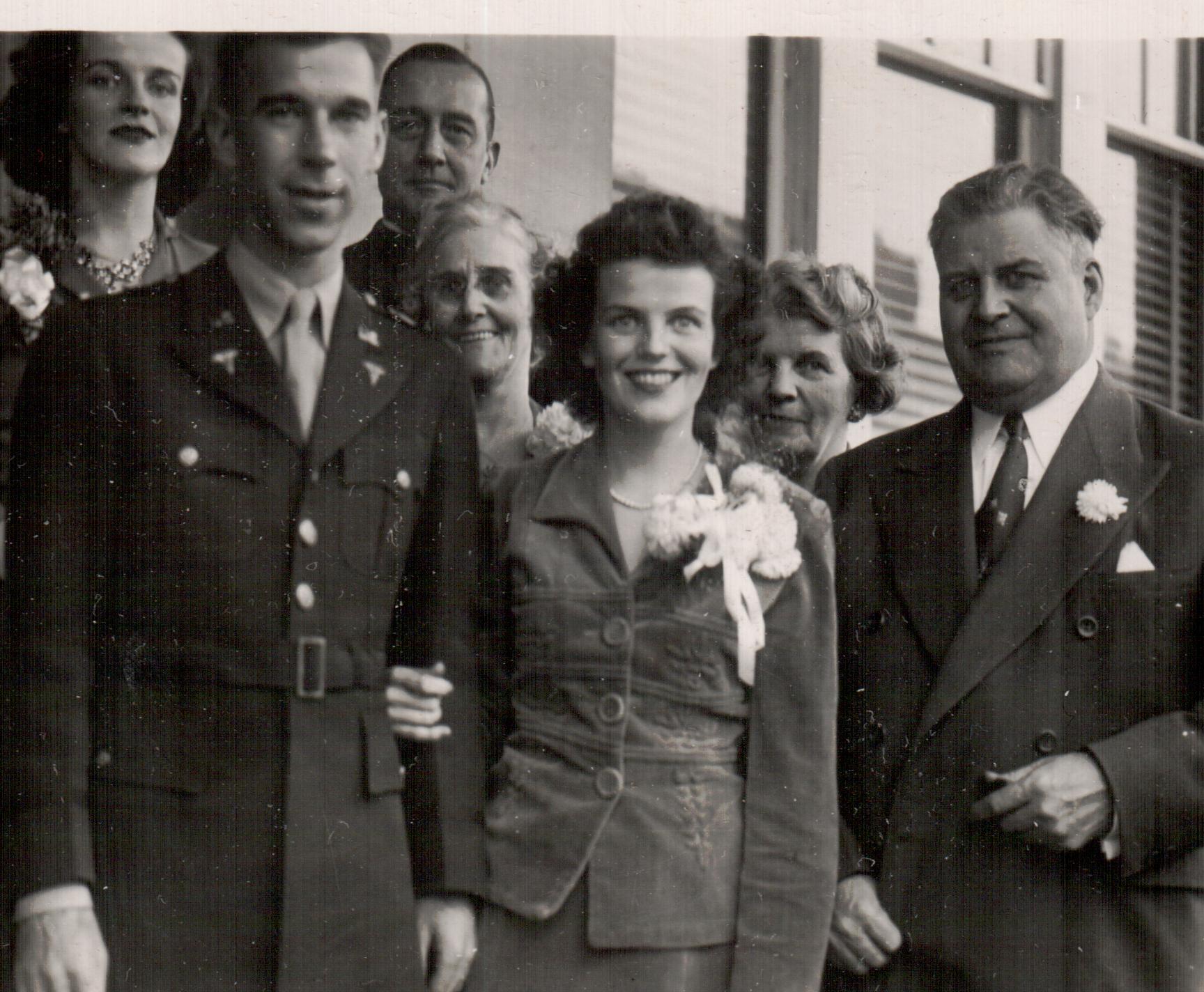

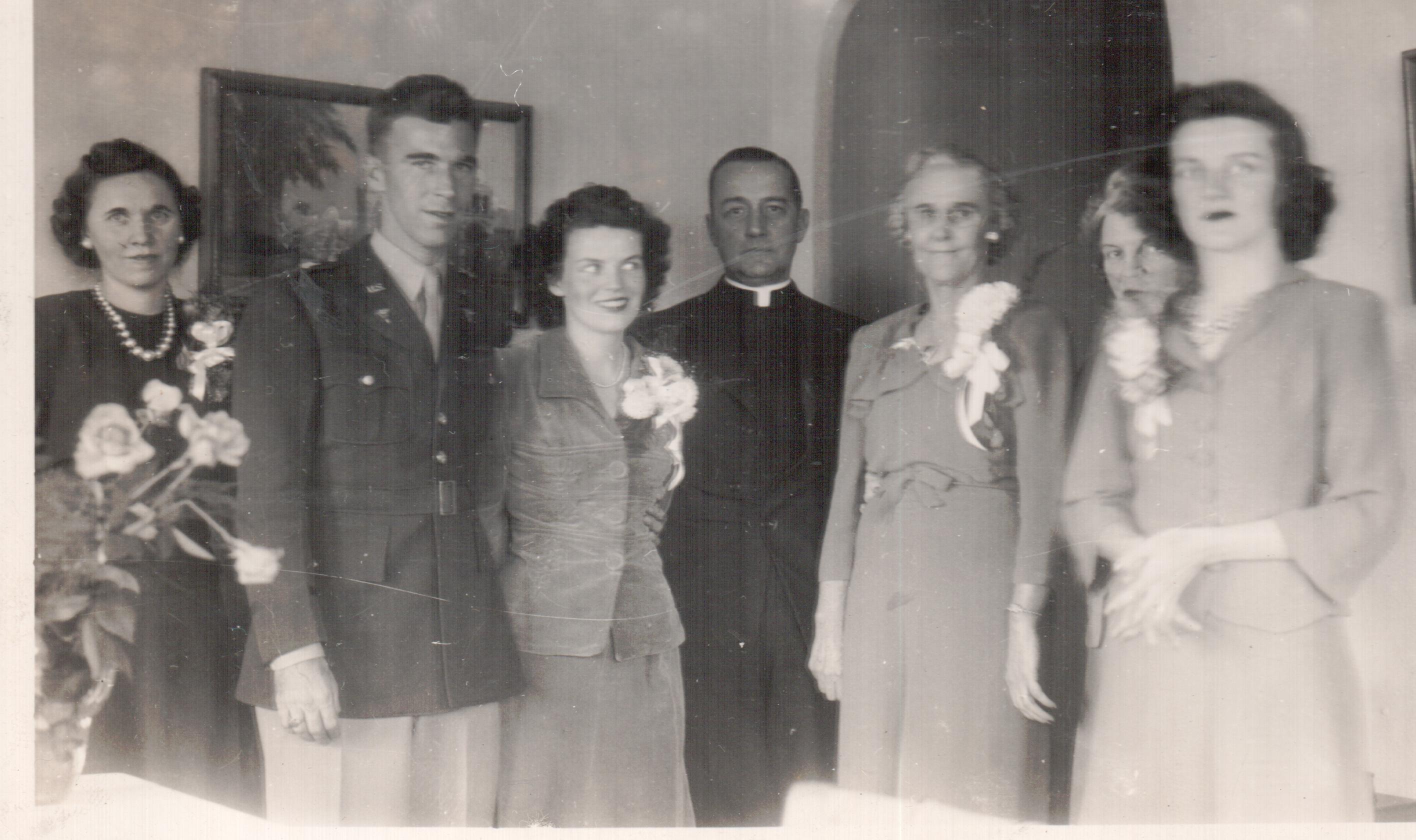

It was at Stuttgart that my parents met in the spring of 1944 when Mom was assigned to the post hospital as [chief] surgical nurse caring for the medical needs of young soldiers wounded in the Pacific Theatre. They met under circumstances not uncommon for men and women far from home in the midst of a global war. On the evening of her arrival at Stuttgart, she ate with the other base nurses in the Officer's mess where she was introduced to Dad and the other male officers at the hospital. The next day after work, she was walking around the base looking for the post office where she planned to mail letters home. She got lost because nearly all the buildings looked alike – the long, white, wood-framed one story structures characteristic of military structures during that war. At one point she noticed a large group of men in overalls on the other side of a fence and she approached them to ask for directions. They enthusiastically offered assistance, although in such heavy accents that she had trouble understanding them. About this time an officer approached her in a jeep and asked her if she needed assistance. The first lieutenant in the jeep was my Dad and he took her to her destination. He also explained to her that the group of men with whom she was fraternizing was a detachment of German prisoners-of-war. My mother was unaware that Stuttgart was not only an army air base but also a large POW facility. She was immediately struck by my Dad's easy, soft-spoken ways, his intelligence and his sense of humor. They were an attractive couple.

Not long after they began dating, an assembly was called for all hospital personnel where the commanding officer, Colonel Ryan, notified everyone that large crates of oranges were disappearing from the hospital at a prodigious rate. Dad informed on my mother, explaining that his girlfriend was manually squeezing the oranges into pulpy juice and serving the patients. She was a big believer in the efficacy of vitamins and none of the recovering patients on her ward lacked for Vitamin C. When Dad told me this story I was not surprised.

Throughout the childhood of me and my siblings, Mom had a propensity for filling our glasses to the brim with orange juice. For as long as I can remember, she force fed us this juice and justified the routine by citing health benefits. Interestingly she was doing the same thing in 1944 for those seriously wounded soldiers of the Pacific Theatre.

Photographs I have of my parents during their courtship at Stuttgart reveal of couple smitten by love. They met in March of 1944 and were married the following November at the Riceland Hotel in Stuttgart, in a private ceremony whose simplicity was in keeping with wartime restraint. When in February of 1945 Mom learned that she was pregnant, she applied for separation from the army. It took a month for her papers to be processed and in March she left for Detroit to live with her parents, to prepare for my birth, and to await my father's separation from the military. While my parents wrote love letters to each other and spoke of a bright future devoid of kaki and regimentation, world events were moving with inexorable momentum toward the conflict's finale. By the time Mom reached Detroit, American soldiers had just crossed the Rhine and were racing into the heart of Germany while Soviet troops were smashing into Germany from the East. Within weeks Franklin Roosevelt would be dead and two weeks later, at the end of May, Mussolini and Hitler would be history.

Soon after Mom left for Detroit, Dad was transferred to Exler Field outside of Alexandria, Louisiana, his final duty station. He was still in medical administration under the command of Major Ghatti, an army officer and a physician. Dad lived on base in a canvass-roofed hooch for about a month until Mom arrived by train from Detroit after which time they rented a room in a private home in nearby Alexandria and took their meals together in town. By the time she returned to Detroit a few months later, war news was bright and Dad could sense that he would soon be out of uniform. The war in Europe was already over and the conflict in the Pacific was nearing its conclusion. Dad knew that because he had been in service since July of 1941 – five months before Pearl Harbor, he would benefit from an expeditious demobilization.

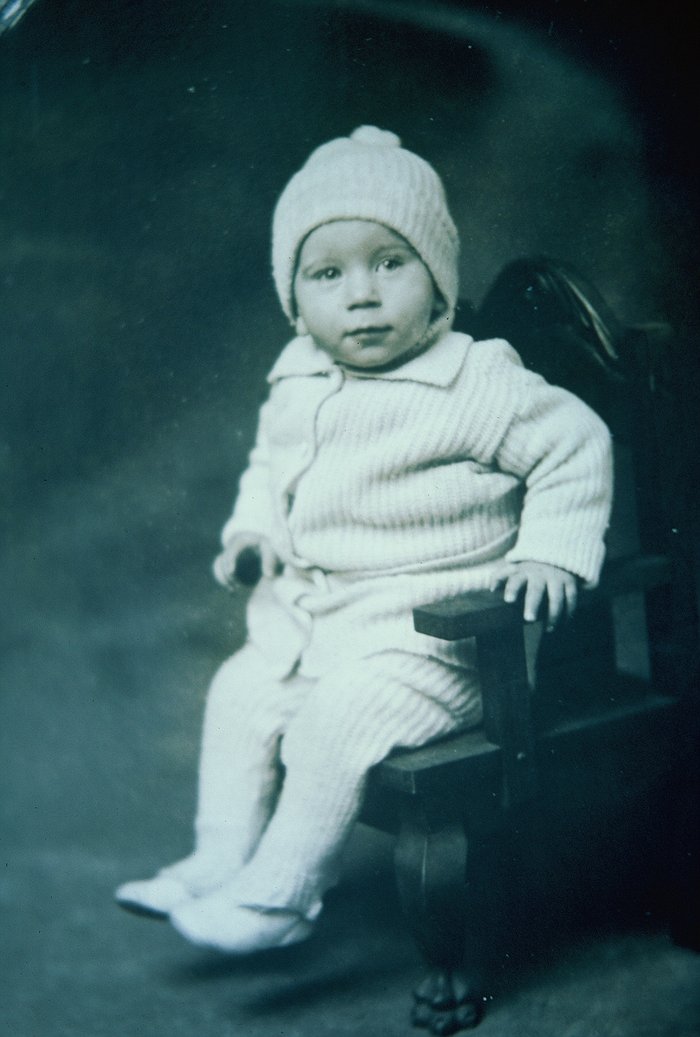

I was born at Grace Hospital in Detroit on 14 November 1945, three months after the end of World War II. Dad was visiting Mom in Detroit at the time of the birth and, while on leave, helped my maternal grandparents move into their new and imposing home on Oakman Blvd. Their previous dwelling on Monica, two blocks away, had been my grand-parents' residence since 1926. The new home was a large structure, a mix of Tudor and Gothic in architectural style, with a large garage that Gampa converted into an office for his Michigan Drilling Company. At the time of my birth, Dad had only one more month left in the army.

Dad left the army as a captain in early January of 1946. As he was in a hurry to complete law school, he reapplied to Vanderbilt only to discover that in the dislocation of war the law school was temporarily closed. He decided to finish his last year at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville and rented a room for us in a spacious private home that before the war was a Catholic retreat house. There were only two rooms available for rent and the other one went to a first year law student who lived with his new bride. Like Dad, he was a veteran taking advantage of a very generous GI Bill to pay for tuition, books and living assistance. I was only two months old at the time of our move to Tennessee and, of course, have no recollection of the eight months we lived in Knoxville. Mom's prodigious affection for photography, however, gives me a visual record of that time and, as always the case with the first-born, most of the pictures were of me. While Dad was in class, Mom carried me on walks into the fields behind our house to experience nature. On weekends there were picnics with cows grazing in the background. One photograph on the front porch swing shows me offering a graham cracker to my mother. To this day I still am in the habit of dunking graham crackers into milk. We lived in this bucolic setting of Knoxville until Dad got law degree. In a graduation photograph with Dad in cap and gown holding me and with Mom's hand on her husband's arm, my parents looked happy and contented.

It was obviously a time of optimism with the war over, couples getting married, a baby boom beginning, and feverish spending after four years of national thrift and rationing. A photograph of the University of Tennessee's incoming class of 1946 reveals something of this optimism in the expressions of male students registering for courses in coats and ties. Their dress and demeanor reflects a class of men who were older, more conservative and more serious than the typical incoming class of college students. They were, like my Dad, veterans returning to school on the GI Bill. This was the so-called Greatest Generation, young men who didn't complain about tough course loads and intimidating professors because life was now gravy for them. Just months earlier they were sleeping in fox holes, experiencing combat, and distant from families they loved.

With a law degree under his belt in September of 1946, Dad moved Mom and me to Nashville where he planned to study for the bar exam and look for a house. As was typical across the country, housing was in short supply after the war and we were forced to live with Grandmother Andrews and Aunt Sara for several months. Dad could not practice law until after he took the bar exam so he worked in management for Southern Bell at the company's Nashville office. Mom was pregnant with a second child, Dad was studying and working, and tensions began to grow between Mom and her in-laws.

Aunt Sara and Grandmother to an extent exhibited the stereotypical Southern WASP prejudice against Catholics. To make matters worse, Mom was a strong-willed Northerner who seldom let slights or barbs go unanswered. Aunt Sara and Grandmother let Mom know that they disapproved of her being pregnant again when Dad had not yet obtained a position in a Nashville law firm. They not only communicated their dissatisfactions to Dad, but in the subsequent decades they would also tell me and my siblings repeatedly that it was my mother who stifled Dad's ambitions and saddled him with too many children. The friction never ended. My earliest memories of Aunt Sara coalesced around the toy drawer she opened for me and her animated denunciations of my mother. Into adulthood I got along well with my aunt and grandmother because I generally didn't come to Mom's defense and simply remained silent during their denuncations. My more undiplomatic sisters, however, were much more willing to defend Mom and, in consequence, always remained emotionally at arms length from Aunt Sara and Grandmother.

January 1947 was a good month in the history of my family. My little brother John was born on the same day that Dad received word of his passing the bar exam. This was also the month that we moved into a home of our own on Stokes Lane. The house, in the Belmont area of South Nashville, was a convenient five minute walk to Christ the King Catholic Church where Mom attended daily mass with her children and about six blocks from Grandmother and Aunt Sara. During the three years we lived in our little yellow-stone home on Stokes Lane, two additional children were born to my parents. By the end of the decade, I was one of four children. My sister Joan was born in 1948 and my sister Susan was born the next year.

Because we were so close in age – only fourteen months apart – we were never lonely. Mom remained home to dote on us and Dad continued to work in management at Southern Bell. He never practiced law. To this day Mom claims that it was because Dad did not like the contentious nature of law practice and even Dad admits that his distaste for law stemmed much from its proclivity to win cases rather than to seek truth. To this day, I don't believe Dad regrets his decision to eschew law as a career.

Our little home on Stokes Lane was a protective wonderland for me and my three siblings. We enjoyed a tree-shaded fenced-in back yard that we called "Never-Never Land." It was a perfect life for children growing up and we were never in want for attention and adulation from our parents. There was stress whenever we visited Grandmother and Aunt Sara but it was not because we were sucked into the verbal crucible of denunciations against our mother. We were too young at that time. However, as the oldest of four children, I can remember by 1949 that Dad would often have to endure the diatribes against Mom – her Catholicism, her affection for having many children, and her hard-headed unwillingness to take advice. By the end of 1949 I can remember that after our weekly visits to Grandmother and Aunt Sara, loud and animated arguments would ensue at home. Mom refused to accompany us on these visits and Dad was torn between loyalty to his family and loyalty to his wife. We felt loved but we could also sense the tensions aroused by the animosities of our mother and her in-laws.

Chapter Five Uncle Sam and Viet Nam: First Draft

The summer of 1967 was one of the most fruitful when it came to arrowhead hunting. It was also the season of much reading. As was the custom inaugurated back in high school, I would take an hour or two looking for arrowheads and then, to cool off, head for the spring, kneel on the bedrock at the deepest end of the pool, and, as doctor fish and crawdads scurried for safety, dipped my upper torso into the cold water. Then I would grab a book and knock off a chapter or two before returning to the field. By this summer I began to use a golf iron to break up clumps of dirt while looking for arrowheads. Where I acquired this iron I cannot recall as no one in my family played golf.

No longer thinking about college, I was reading for fun and I went through the books with an earnestness which came from sheer pleasure. The entire family was on the farm that summer with the exception of John who was at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, finishing up his training in ground control radar. There was a great void that summer without John and the entire family seemed diminished in its collective vigor from a pervasive anxiety. Vietnam was on everyone's mind if not on their lips.

I also thought of our family vacation the previous summer. Dad had gone west on an ambitious camping trip with the four older children in our white '65 Impala. The heavy canvas umbrella tent and sleeping bags were strapped to the roof and cooking gear was in the trunk. We saw the Garden of the Gods near Colorado Springs, visited the Custer Battlefield in Montana, and hiked around Mt. Rushmore and Devil's Tower. Camping out each night in state or national parks, we followed a rudimentary agenda set by Dad to entertain and educate us. The majestic Rockies, in particular, stood in stark contrast to the older and more familiar Appalachians.

When Dad took us to Rocky Mountain National Park, John and I got the notion to scale Long's Peak, at 14,000 feet one of the highest in that cordillera. We began early in the morning, leaving Dad and the girls to watch the wedding of Lucy Baines Johnson, the president's older daughter, on the miniature B&W battery powered TV which Dad brought for his never-to-be-missed Huntley-Brinkley newscasts. John and I reached the mountain's boulder field by mid-afternoon and, although winded easily from the thin air, enjoyed a snowball fight at a slightly higher elevation. By dusk we stopped directly under the last leg of the climb realizing that without pitons and ropes, scaling the summit would be hazardous in the dark. We rested until darkness descended and viewed the distant lights of Denver. It was peaceful and serene up there, reminding me of the poem by World War II pilot _____ Campbell airing frequently on television like a soap commercial. " …I can "reach out and touch the face of God." This would prove to be the last summer in many years before John and I would share such a sublime moment.

So now a year later I was looking for arrowheads and finding them by the score each day. One of the books I devoured that summer was "The Arrogance of Power" by Arkansas Senator J. William Fullbright who had acquired the reputation of a hardhitting war critic in his role as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. I also read William Lederer's "A Nation of Sheep," Dostoesvski's "The Idiot," William Manchester's "Death of a President," and Thomas Hardy's "Return of the Native." I also finished William Shire's "Rise and Fall of the Third Reich," a book which I began early in my sophomore year at St. Louis [see friend Kurt von Schuschnigg] but which I had abandoned due to required assignments and Joan's request for it. She had the bulky volume read within weeks.

Although only a year away from graduating with a major in political science, my interest was increasingly moving toward history. I could see this change most dramatically a year earlier in my SLU political science classes with Drs. Legeay-Feueur and Daugherty. Now in the arrowhead field, I could remember the historical anecdotes they employed to illustrate the theories that had been long since forgotten.

We heard that John, as he was finishing up his training in New Jersey, would be reassigned soon and it was anyone's guess where. I spoke to Joan and Susan about a quick trip to see John, got the OK from Mom and Dad, loaded up the VW bug, and took off with Joan and Susan on another fine adventure, my last before leaving for the army myself.

Fort Monmouth provided family visitors with special quarters at a very reasonable rate so we did not have to break out the tent and camping gear. John was free after 4:00 each weekday and we had an entire weekend together. Once John invited me into his workstation and introduced me to some of his classmates. Without thinking, in a sector of the high tech satellite and communications center, I took a flash photo of John standing in front of some highly classified equipment. It didn't dawn on me until later that it was the Ft. Monmouth soldiers who came under investigation by Senator Joe McCarthy for treasonable espionage thirteen years earlier.

We spent the weekend with John at Asbury Park and its beaches. Susan had a little romantic fling with a young man by the name of Jeff Goldstein whose mother was proprietor of a shop on the boardwalk and Joan served as an invited chaperone. John and I flirted with two girls who looked great in their bathing suits but who were too young to take seriously. Interestingly, the girls spoke about how they supported the right of women to have an abortion. I had never considered the subject before and I frankly cannot recall the conversational tangent that conveyed us to this topic. I remember them telling us that they were Reformed Jews.

If it was an idyllic weekend at the beach, what I saw at the military installation gave me some reason for trepidation. For one thing, John hated his military service and was extremely homesick for family and St. Louis University friends. He had the sense that he was wasting time, not learning much, and constantly subject to the whims and machinations of superiors whose only claim to authority was an extra stripe or a little more time in service. It was an inauspicious introduction to the life that awaited me.

Looking back on it, I must confess that we were all aware of college deferments and we knew that all it would take was a letter from Father McGannon, Dean of Students, to verify our status as students in good standing at an accredited university. But we never went that route. Perhaps we should have but I speak from present prejudices and predilections. In fact, John and I had talked of this before. We felt that many people were flocking into colleges and universities all over the country for the wrong reasons. College had become a haven for many young men who, except for the fear of Nam, would otherwise have been content elsewhere. And conversely, many young men were fodder for the cannons with SAT scores too low for college admissions or, if sufficiently endowed with intelligence, with insufficient financial resources to afford a higher education. Of course, this was before the days of inexpensive and accessible community colleges or readily available tuition assistance. The irony was the Higher Education Act, a Johnson priority for his Great Society agenda, was being trumped by the president's increasing obsession with the war. As Johnson later said "The Great Society was the woman I really loved and the war was the..." -well you know the rest. In any case, we felt the draft was inherently unfair, favoring the rich and the well connected and victimizing the poor and academically unprepared.

There were other reasons for our unwillingness to seek deferment status. Admittedly John and I were both getting a little bored with school and we also knew that Mom and Dad were making some very real sacrifices for an education which we ourselves could not appreciate at the time. Perhaps we were ready for some travel and adventure which, in our naiveté, did not include combat zones. And there was another reason. Mom and Dad had both been officers in the Second World War and had served their country selflessly. I cannot speak for John but, as for myself, I did seek parental approval and thought that to make a dramatic appeal before the draft board in Nashville would look cowardly. Such are the concerns of uncynical youth and I suspect there were many others who enlisted in those years for reasons of parental or peer approval.

I entered the army on 21 September 1967 with little fanfare, waving goodbye to my family as my olive drab bus left the Nashville induction center for Fort Campbell near Clarksville, about an hour's drive north. I recall that there was little talking on the drive up. Few people knew each other and most, I suspect, were like me spending the time reflecting on an uncertain future. Most of the men were young draftees.

Basic training was not the culture I had anticipated. Living for two years in a men's dorm at college was an experience that imparted some important social and survival skills. There was a decided pecking order which was obviously based on physical prowess but there was also – and this came as a surprise to me – respect shown for intelligence and common sense. The shock for me was the extent to which boys in my company were physically unfit. Many had difficulty on the obstacle course. Many feared heights. Many were easily exhausted by the rigors of forced marches and bivouac. The fact that John and I during high school and college routinely ran ten to twenty miles cross country – and this was before jogging became a popular fashion – made the marches easy. On the mile race under full backpack, helmet, boots and M-14 rifle, I was always one of the first to reach the finish. I actually enjoyed the obstacle course and felt that my years playing tennis helped with balance and coordination. When we crawled through the mud at night, negotiating our way under concertina wire and machine gun tracers over head, it was no big deal. In fact, it was sort of fun.

On our first day at the rifle range, we were ordered to fire live rounds at a target just thirty meters away to scope in our M-14 rifles. I was told to fire three shots at the target and retrieve it. When the drill sergeant looked at mine he stopped and told me to put up another paper. I was told to fire three more shots. I did. After the third sequence, the DI took my paper targets and walked over to the other instructors. Whatever he told them, they all looked over at me. In each of my targets, the pattern of three shots all could fit within the size of a dime.

On our march back, the senior drill sergeant, always rather gruff with me, let slip out of the corner of his mouth in a barely audible report "good shooting, Andrews." I had assumed that most of the boys in our company had done as well.Mine was the tightest pattern of all shooters. One of the trainees told me that I was so good a shot that the DI's would surely recommend me for an infantry sniper MOS at graduation. I gulped hard at the thought.

During our first days in Basic, we had the proverbial buzz haircuts, we were issued our uniforms and field gear, and we were introduced to the high-pressure inoculation guns which replaced the syringe needles of my childhood fears. The blow from these pressure guns felt like a knuckled fist pounding the upper arm. After this experience, I learned to appreciate how little pain was associated with the old needle method. We were given our army ID numbers and ordered to memorize them upon penalty of death. Although I have trouble remembering the names of my college students from last year, I can still remember "US53908912," the number impressed on my dogtags along with my name, my faith and my blood type.

[Cont'd son Joel]

Our first workday was spent with our entire platoon on the barracks floor. All of us were in our olive drab boxer shorts and all of us were issued putty knives. We were ordered to scrape all the wax off a well-polished floor. The next day we waxed and buffed. The reason, I gathered, was to strip away our dignity in layers as we were stripping away the wax.

It was to instill in us a sense that we were an organic unit all working together for a common objective, building us up to be reflexively obedient, unquestioning instruments of war. And woe to the individual who asked for an explanation or who complained openly. It was a psychology that worked.

I got the impression that my drill sergeant knew I didn't buy it. Most of the boys in my unit were two to three years younger than I and few had anything more than a high school education. I suspected that some didn't even have that. The reason why the military preferred young and impressionable youths was made abundantly clear to me when we had a company assembly in an indoor arena during our third or fourth week of Basic.

Our platoon leader was a tall, skinny redheaded second lieutenant who seldom said anything to us and who just walked around returning salutes. He was probably fresh out of ROTC but he looked like he was eighteen and so bewildered by his new responsibilities (returning salutes) that our foul-mouthed, chiseled-faced, battle-hardened DI's could have waffled him down for breakfast.

In any case, at the assembly we heard the lieutenant speak publicly for the first time. It was a short address, probably meant to be motivational, but it faltered somewhat. He seemed somewhat diminished in the presence of all those beefy, leather-faced DI's. He was followed by one of the DI's who walked on the stage and began to cuss all the hippies and radicals who were badmouthing the war. Everyone was listening intently and I was trying to figure out where he was going. Then he said that during the previous year more than thirty thousand Americans had been killed in car accidents on our highways. He paused. Then he bellowed out "so what the hell are all those s___-faced pacifists complaining about when only ten-thousand American soldiers got killed in Vietnam last year? Why don't they complain about them what was killed on the highways?" With this the crowd of soldiers, almost to a man, yelled out their enthusiastic accord. "Yeah!!!" Looking around, I could not help the forlorn thought that it would be a long two years.

I was smart enough to keep my mouth shut about my antiwar sentiments in front of the DI's but in bull sessions in the field or at night in the barracks, the guys in my platoon began to talk to me about their anxieties. My nickname became "professor." My only serious confrontation with my drill sergeant occurred the day when we were fighting each other with pugil sticks and football helmets. I had befriended a couple of Puerto Rican recruits who were in our company but whose platoon was assigned to an adjacent barracks. After the fourth week, the discipline was relaxed enough where, after mess, we could fraternize with men of our company in other barracks. These Puerto Riquenos were teaching me some of their songs on the guitar and I was trying to improve my language skills after two semesters of Spanish in college. On the pugil course, our DI was unusually insulting to the Hispanics, calling them Spics, ____ and "__ for brains." What occasioned some of this animosity, beyond simple prejudice, was the fact that the Puerto Ricans were part of a reserve unit activated only for our eight-week basic training course after which time they would return to their civilian jobs back on their island paradise. At any rate, I got tired of the sergeant's tirade and called out to him "why don't you leave them alone." There was a dead silence. The DI turned and walked up to me and smiled. "Andrews," he said with an even voice, "I want you to be the first to demonstrate the pugil stick." He handed me a stick and ordered me to the center of the group. He handed the other stick to the biggest draftee in our unit, a giant of a man who had the physique of a serious bodybuilder. The sergeant handed him a football helmet and told him to beat the __ out of me. When I reached over for a helmet, he told me that my head was too big to fit any of those on the ground.

My opponent, whose name I can not remember, went on to become a friend and, when we graduated, told me he was assigned an MOS as a military policeman. As per instruction, he didn't hold back and I was on my back after just a couple well-laid-on blows. If I had some bruises and a headache that lasted several days, I also had a lot more friends among the Puerto Ricans and Mexican-Americans in my company. And the biggest surprise was that the sergeant seemed to ease up a bit more after the incident.

We went back to the rifle range several times and I always did well. In fact, after knocking down my human cut-out targets, I sometimes turned my M-14 to fire on the targets in the adjacent lanes. Most of the DI's from the other platoons saw some humor in this. They got together and suggested that I compete with the best shot in another company of two-hundred men. The next morning after our 5:00 am breakfast mess, the company marched out to the rifle range. When we arrived, we noticed that another company was on site milling around and waiting for us. My recollection is that many of them were on some bleachers. There was a steady drizzle this morning and, as we were now in early November, the light was low. The DI's ordered me and the other company's sharpshooter to take our positions and prepare to fire on our respective pop-up targets. I was ordered to fire first. We were the only two on the line to fire.

I had a pair of glasses issued me during the first week and I only used them when on the rifle range. The cold rain increased and my glasses began to fog up as soon as I put them on. After adjusting my rifle's rear sight for elevation, the targets popped up. The cold air and my expirations fogged up the glasses even more as I fired away. I missed many of the targets, particularly in the prone position which was usually my best position for firing. The sharpshooter from the other company bested me. Through the grapevine I learned that my DI had bet a bunch of money on me and had lost. Remembering how he had me disciplined in the pugil beating, I considered his lost money poetic justice.

In the last weeks of Basic we were given a few more privileges, the most prized of which were the visits from loved ones. On several occasions Dad and Joan drove up from Nashville to visit on Sunday afternoons when we were free from work or drilling (so long as we confined ourselves to the base). I considered myself particularly lucky with family so close. Few of my comrades enjoyed Sunday visitations. On the second trip they brought my youngest siblings, David and Miriam who had recently turned ten and eight respedctively. They would always bring my favorite treat, a carton of milk and a box of Keebler coconut chocolate chip cookies. I devoured them in ecstasy as Dad and Joan brought me up to date on family news. Although these visits were the only gifts I cherished during basic, they probably left me afterwards in an even greater state of demoralization. More than anything else I gained from my two years of military service, it was an appreciation for personal freedom.

My most anticipated visit came from John as my eight weeks of training were drawing to a close. He was a PFC stationed at Fort Carson, Colorado, and he told me about his adventures and adversities. He was taking classes part-time at the university there and he told me about how he ran into Olympic skater Peggy Flemming at the school library. In retrospect, I believe that John suffered much more than I did from the harassments and humiliations from the army's pecking order, and the arbitrary edicts of petty, small-minded men with a power they could never expect to exert in the fluid and freewheeling civilian world. When John and I shook hands as he was about to leave, I could not control it, hard as I tried, but my eyes watered up and I had to turn quickly away before I embarrassed myself more. I remember thinking what a good brother John was. He was the most sensitive of my siblings, the one who broke down and cried when Milton Evans, our black sharecropper, died. Years later when Ganger died, it was John who broke down and sobbed. The irony was that Ganger always showed more favoritism toward me, showered me with more gifts, and requested that I be the one to stay with her in Mobile. Of all my siblings, it seemed at the time that John had the greatest capacity for sentiment and yet, like Mom and my sisters, was also somewhat disinclined to compromise. These traits would make the regimentation of military life very difficult for him. He was eventually made a Chaplain's assistant.

On graduation day I learned that I had been assigned to Fort Polk, Louisiana for AIT (advanced infantry training). My assigned MOS (military occupational specialty) was 11 Bravo, the designation for an infantry rifleman. I began to think that my pride on the rifle range had trumped my common sense. On the other hand, in true paranoid fashion, I thought that perhaps my DI had gotten the final revenge. Once more familiar with the process of cutting orders, I later realized that a DI likely had little input in the decision.

In stark contrast to my graduation from Father Ryan High, my family was not present for the ceremony at Fort Campbell. In truth, I did not wish them to be present. As I walked back to my barracks for the final time with Fort Polk orders in hand, I noticed a new batch of recruits, all on the floor stripped to their shorts, with putty knives in hand, all quaking under the thunder of our ex-drill sergeant's demonic-sounding tirades.

In one of many fortuitous incidences in my life, I had a piece of good luck when I arrived at Fort Polk. Few recruits in an infantry MOS had any illusions about their future duty location after Louisiana. Nearly all would be shipped out to Vietnam at the end of their eight-week AIT session. One is not trained at Fort Polk's Jungle Warfare Training Center to be sent to Germany or Korea.

Our bus arrived at the sprawling infantry-training center about 10:00 in the evening and as we stepped from our vehicle I noticed a dramatic difference in the climate. It was late November. Just a week before during bivouac at Fort Campbell, we experience some very cold weather. The temperature in Louisiana was by contrast warm and humid despite the late hour of our arrival. After gathering our gear from the belly of the bus, we queued up for registration and assignment to our infantry training units and barracks. My line moved closer to the registration table and there was only one soldier in front of me when a staff sergeant stepped up to us and asked if anyone in our line could type. Several of us raised our hands. We were taken out of the original line and ordered to queue up in another line. We had our MOS's changed and, instead of the infantry, we were reassigned to an administrative training school at the same base. Although I didn't know it at the time, an incident had occurred to alter Uncle Sam's plans for me. The infantry barracks were filled to capacity and arrangements had to be found for additional quarters. Exacerbating the housing shortage was a recent outbreak of meningitis in which some young recruits in the infantry barracks had died and a quarantine temporarily closed down their buildings.

For the next two months I was trained in administration to be an army clerk and my MOS was changed to 70 Bravo. Mom had taught me to type on Dad's old portable Royal typewriter and more recently I had been typing term papers for myself and other students at SLU. I had also typed up reports and papers for other students. Even before the army's clerical school I was typing sixty words a minute.

Fort Polk was one of the bleakest military outposts imaginable north of Antarctica. The nearest town was Leesville and its only excitement was at the Greyhound Bus Station and a drab USO club. The fact that the surrounding counties were dry certainly added to the sense of desolation. The base was known for its jungle survival school and its training in counter-insurgency warfare. On marches into the swamps and bayous, soldiers made it a point to take the snakes they killed and hang them over fences on the side of the roads. Even though I was now in administration, some of our training overlapped with that of the infantry and we would sometimes go out on joint maneuvers. I will never forget the smell of decomposing reptiles, pungent swamp waters, and decaying vegetation that permeated the atmosphere. The only source of entertainment open to me, it seemed, was checking out books from the base library and meandering through the PX looking for creature comforts to buy. It was truly a dead base adjacent to a dead town. Lewisburg appeared like Greenwich Village by comparison.

In another fortuitous twist, my orders came down in early January 1968 for my first post-training duty assignment. It was not Vietnam as I had feared but rather the United States Military Academy Prep School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, just to the south of Alexandria and Washington, DC. To say that I was elated would be understatement. With only a stopover for a couple of days in Nashville to see the family, I flew to Washington and took military transport to Fort Belvoir, a major Corps of Engineers base on the Potomac.

The prep school functioned as a feeder institution for West Point where men already in the army with promising IQ's and high ACT or SAT scores could take military and academic courses which would get them up to speed for entry a year later to the Academy. My work was as an administrative clerk for Major Chandler, the vice commander of the school. It was a plush assignment by any army standard. When I arrived I was given a room much like what I had as a student in Clement Hall dormitory at SLU. My roommate was Frank Anselmo, another clerk from Spokane and a college graduate. I remember that he was a trekkie who could recount in detail every episode of the science fiction TV series. It came as no surprise that he loved Italian cuisine and music. On various weekend trips with him to Washington, we canvassed the city for restaurants and record shops that catered to his tastes. With a room to ourselves and with Washington just a half hour away, the Prep School with its Federal brick architecture exuded the atmosphere of a sleepy Ivy League college.