PANAMA, HONDURAS, EL SALVADOR

4-228th Battalion Commander, killed in El Salvador after his helicopter was shot down by rebels

Author Murry Engle, published in USA TODAY, Arlington, Virginia, on January 26, 1991:

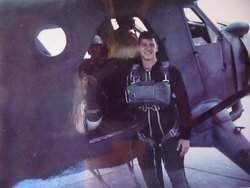

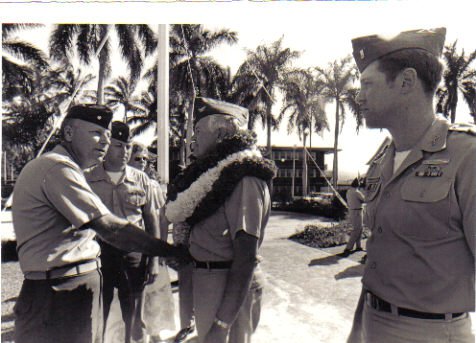

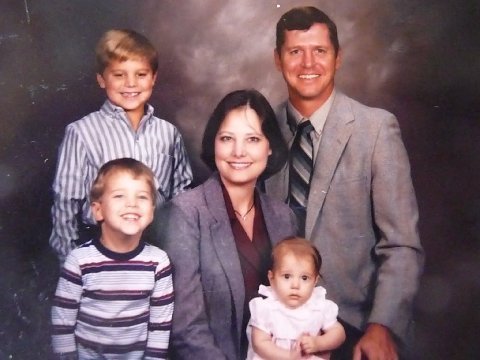

Edward and Grace Pickett go to Mass each morning. She swims in the ocean each day. He writes letters. As parents of eight children, they have many grandchildren around them. But Ed, a retired Army lieutenant colonel, and Grace are grieving. One of their eight "Army brats," Army Air Battalion Commander Lt. Col. David Pickett, was killed Jan. 2 by leftist rebels in El Salvador. His parents remember the bright days of David's life: sharing a secret language with his twin, Carol; 6-foot-5 Dave taking the oath from his 6-foot-2 dad at West Point graduation; flying with his sports parachute team; marrying Army nurse Lt. Col. Rosemary Griggs in Hawaii; having three children. But their strongest image now is the horror of David's last day, when rebels downed the helicopter he and two other military advisers were flying in eastern El Salvador. The navigator died on impact. David and the co-pilot were injured. Rebels claimed all three men died in the crash, but a U.S. forensic report said the rebels came up to the injured men and killed them "in cold blood," shooting them in their faces. The Picketts, who have lived in Honolulu 21 years, last talked to David, 40, by phone a couple of times on Christmas Day. "I'd been arranging to go to Honduras for his Jan. 16 change of command, to be his honorary platoon leader, like he was for me when I retired from the 25th Division at Fort Shafter in 1975," Ed Pickett said. David was scheduled to complete his tour as commander of the 4th Battalion, 228th Aviation Regiment, under the U.S. Army South in Panama. He was the senior Army aviation and safety officer for U.S. units in Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Belize and Nicaragua, and an adviser on aviation employment in those countries. "He was on the fast track," said the senior Pickett. After the change of command, David was to go on to Ft. Rucker, Ala., for aviation command combat development, then to War College, a major step in moving up the Army career ladder. His last efficiency report said Pickett's was the "most demanding battalion command in the Army" and that he and it have done "more for the image of the United States in the region than any other U.S. resource." "Although he achieved a lot, he was average, not exceptional, and had to work very hard," Ed Pickett said. "But he was very competitive." The change of command took place without either Pickett present. During the ceremonies, Camp Black Jack in Honduras was renamed Camp Pickett. The Picketts and other family members traveled to Fort Campbell, Ky., to be with Rosemary and the children and to attend memorial services Jan. 7. Two days later, David was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Not present was another son, Ed, an Air Force staff sergeant stationed in England, who is helping provide supplies to his unit in Saudi Arabia, where he expects to be sent. Shortly after the killings in El Salvador, the Bush administration, in support of the El Salvador government, said it would release $42.5 million in aid that it had frozen because of human rights complaints. Rebel leaders in El Salvador last week charged two of their men with "crimes of war and violating Geneva Protocol" for the Jan. 2 killings. What happens now is questionable, a military spokesman here said. The Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front won't turn over the suspects to the El Salvador government; a tribunal of rebels and independent representatives is supposed to try them. "We certainly are in hopes they would be brought to justice," said Ed Pickett. "If the FMLN does what it says it will, we could ask no more." Ed Pickett read from a letter David wrote to Rosemary after undergoing fire during the U.S. campaign to oust Panama's Manuel Noriega: "It reaffirms my belief that military people want war least of all, because we have the most to lose." "That's the way he was and the way I was" through three wars and 33 years of service, Pickett said. "If you have that dedication, it's the way things are supposed to be. That's what makes it so hard. "Some will say he shouldn't have been there (in El Salvador). People on the government side have committed wrong acts, like killing a priest. They should be punished the same as David's murderers. But the people of El Salvador have voted for the government there."

Published in the New Haven Register, New Haven, Connecticut, on January 10, 1991:

Salvadoran rebels admitted on Wednesday their forces may have executed two U.S. servicemen aboard a helicopter they shot down, and they pledged to punish anyone found to be responsible. The Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front said in a communique that two of its fighters had been arrested on suspicion of "having assassinated wounded prisoners of war." The downing of the helicopter Jan. 2 and charges that two of its crew had been executed apparently played a role in President Bush's decision this week to ask Congress to restore $42.5 million in withheld military assistance to El Salvador. The money had been frozen because of what the administration said was a lack of progress in solving several human rights cases in El Salvador. Other reasons for Bush's request included contentions that the rebels continue receiving weapons from outside the country, especially sophisticated surface-to-air missiles. The helicopter was on a flight from San Salvador to Honduras and was flying low to avoid surface-to-air missiles when it was shot down with small arms fire near the village of Lolotique, 80 miles east of San Salvador. A U.S. military investigation showed that Army Chief Warrant Officer Daniel S. Scott, 39, apparently was killed outright in the crash. Further autopsy reports showed, however, that Pfc. Earnest G. Dawson Jr., 20, and Lt. Col. David H. Pickett, 40, survived the crash but were later shot and killed at close range. The reports indicated both had several wounds from at least three weapons. At first the FMLN denied the killings, then said it would investigate them. The group also said the helicopter was shot down only after it fired on a local village - a claim denied by U.S. officials. On Wednesday, the rebels said a preliminary investigation showed there were "sufficient elements to presume that part of the crew, as wounded prisoners, could have been assassinated by one or several members of our military units." The FMLN said that shooting down the helicopter might have been justified, but shooting wounded prisoners was not. It said that if further investigation proves guilt, those responsible will be severely punished. The rebels did not specify what the punishment would be, but said it would be rigorous and in "accordance with our regulations for justice during wartime, which contemplate respect for human lives, for prisoners of war and for the civilian population." The statement said the action had "serious implications for the public image of the FMLN and its National (Rebel) Army."

PANAMA, HONDURAS, EL SALVADOR

4-228th Battalion Commander, killed in El Salvador after his helicopter was shot down by rebels

Author Murry Engle, published in USA TODAY, Arlington, Virginia, on January 26, 1991:

Edward and Grace Pickett go to Mass each morning. She swims in the ocean each day. He writes letters. As parents of eight children, they have many grandchildren around them. But Ed, a retired Army lieutenant colonel, and Grace are grieving. One of their eight "Army brats," Army Air Battalion Commander Lt. Col. David Pickett, was killed Jan. 2 by leftist rebels in El Salvador. His parents remember the bright days of David's life: sharing a secret language with his twin, Carol; 6-foot-5 Dave taking the oath from his 6-foot-2 dad at West Point graduation; flying with his sports parachute team; marrying Army nurse Lt. Col. Rosemary Griggs in Hawaii; having three children. But their strongest image now is the horror of David's last day, when rebels downed the helicopter he and two other military advisers were flying in eastern El Salvador. The navigator died on impact. David and the co-pilot were injured. Rebels claimed all three men died in the crash, but a U.S. forensic report said the rebels came up to the injured men and killed them "in cold blood," shooting them in their faces. The Picketts, who have lived in Honolulu 21 years, last talked to David, 40, by phone a couple of times on Christmas Day. "I'd been arranging to go to Honduras for his Jan. 16 change of command, to be his honorary platoon leader, like he was for me when I retired from the 25th Division at Fort Shafter in 1975," Ed Pickett said. David was scheduled to complete his tour as commander of the 4th Battalion, 228th Aviation Regiment, under the U.S. Army South in Panama. He was the senior Army aviation and safety officer for U.S. units in Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Belize and Nicaragua, and an adviser on aviation employment in those countries. "He was on the fast track," said the senior Pickett. After the change of command, David was to go on to Ft. Rucker, Ala., for aviation command combat development, then to War College, a major step in moving up the Army career ladder. His last efficiency report said Pickett's was the "most demanding battalion command in the Army" and that he and it have done "more for the image of the United States in the region than any other U.S. resource." "Although he achieved a lot, he was average, not exceptional, and had to work very hard," Ed Pickett said. "But he was very competitive." The change of command took place without either Pickett present. During the ceremonies, Camp Black Jack in Honduras was renamed Camp Pickett. The Picketts and other family members traveled to Fort Campbell, Ky., to be with Rosemary and the children and to attend memorial services Jan. 7. Two days later, David was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Not present was another son, Ed, an Air Force staff sergeant stationed in England, who is helping provide supplies to his unit in Saudi Arabia, where he expects to be sent. Shortly after the killings in El Salvador, the Bush administration, in support of the El Salvador government, said it would release $42.5 million in aid that it had frozen because of human rights complaints. Rebel leaders in El Salvador last week charged two of their men with "crimes of war and violating Geneva Protocol" for the Jan. 2 killings. What happens now is questionable, a military spokesman here said. The Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front won't turn over the suspects to the El Salvador government; a tribunal of rebels and independent representatives is supposed to try them. "We certainly are in hopes they would be brought to justice," said Ed Pickett. "If the FMLN does what it says it will, we could ask no more." Ed Pickett read from a letter David wrote to Rosemary after undergoing fire during the U.S. campaign to oust Panama's Manuel Noriega: "It reaffirms my belief that military people want war least of all, because we have the most to lose." "That's the way he was and the way I was" through three wars and 33 years of service, Pickett said. "If you have that dedication, it's the way things are supposed to be. That's what makes it so hard. "Some will say he shouldn't have been there (in El Salvador). People on the government side have committed wrong acts, like killing a priest. They should be punished the same as David's murderers. But the people of El Salvador have voted for the government there."

Published in the New Haven Register, New Haven, Connecticut, on January 10, 1991:

Salvadoran rebels admitted on Wednesday their forces may have executed two U.S. servicemen aboard a helicopter they shot down, and they pledged to punish anyone found to be responsible. The Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front said in a communique that two of its fighters had been arrested on suspicion of "having assassinated wounded prisoners of war." The downing of the helicopter Jan. 2 and charges that two of its crew had been executed apparently played a role in President Bush's decision this week to ask Congress to restore $42.5 million in withheld military assistance to El Salvador. The money had been frozen because of what the administration said was a lack of progress in solving several human rights cases in El Salvador. Other reasons for Bush's request included contentions that the rebels continue receiving weapons from outside the country, especially sophisticated surface-to-air missiles. The helicopter was on a flight from San Salvador to Honduras and was flying low to avoid surface-to-air missiles when it was shot down with small arms fire near the village of Lolotique, 80 miles east of San Salvador. A U.S. military investigation showed that Army Chief Warrant Officer Daniel S. Scott, 39, apparently was killed outright in the crash. Further autopsy reports showed, however, that Pfc. Earnest G. Dawson Jr., 20, and Lt. Col. David H. Pickett, 40, survived the crash but were later shot and killed at close range. The reports indicated both had several wounds from at least three weapons. At first the FMLN denied the killings, then said it would investigate them. The group also said the helicopter was shot down only after it fired on a local village - a claim denied by U.S. officials. On Wednesday, the rebels said a preliminary investigation showed there were "sufficient elements to presume that part of the crew, as wounded prisoners, could have been assassinated by one or several members of our military units." The FMLN said that shooting down the helicopter might have been justified, but shooting wounded prisoners was not. It said that if further investigation proves guilt, those responsible will be severely punished. The rebels did not specify what the punishment would be, but said it would be rigorous and in "accordance with our regulations for justice during wartime, which contemplate respect for human lives, for prisoners of war and for the civilian population." The statement said the action had "serious implications for the public image of the FMLN and its National (Rebel) Army."

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement