The tale of "Granny Dollar," one of the most colorful characters and rugged individualists who ever lived in the Fort Payne area, has long captured the imagination of those who have heard of this Cherokee Indian's century of varied experiences. Assuming that all the information given by Granny Dollar in an interview in 1928 is factual, these absorbing tales of her strange life certainly bear repeating; indeed, the legend of such a rare person should never die.

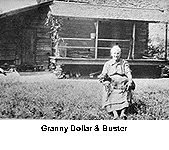

According to an article which appeared in the January 28, 1928 issue of the Progressive Farmer, this friendly old woman, who lived on Lookout Mountain about nine miles from Fort Payne enjoyed reminiscing and talking to visitors. She was Nancy Callahan Dollar, affectionately called "Granny" or "Grandma," though her many experiences never included that of motherhood. She said she was 101 at the time of the interview, but she remembered the early days of childhood well.

Born on Sand Mountain in Buck's Pocket eight miles east of Coffeetown, Nancy was the daughter of a Cherokee father named William Callahan and a half Cherokee Indian, half Irish mother. She enjoyed the games played by Indian children, including one called "dog and fox" and liked to pitch quoits, an activity similar to pitching horseshoes. She never attended any kind of school.

Nancy's father hunted game while the rest of the family raised corn and potatoes. On one occasion after having killed a very large deer, her father appeared to be very sad and unable to eat. The concerned mother, after persistent questioning finally elicited the reason for his distress. "I cannot eat my meat," he said. "I fear my three poor little children in South Carolina are hungry. I have a wife and three children in South Carolina and I was forced to leave them there." Nancy's mother replied, "Go and fetch them. There is room and plenty to eat."

Thus it was, that the family soon included another mother and sister and two more brothers. The Cherokees were allowed to have more than one wife and in Nancy's family, at least, there appeared to be no dissension or jealousy. She remembered that her mother appeared as happy over the new arrivals as did the children and had her big dirt oven full of baked potatoes and venison ready for the ravenous children. The two women labored together in raising the crops and caring for the family. Together, they had a total of 26 children, including three sets of triplets born to Nancy's mother.

This large family ate wild turkey, deer and fish with vegetables, which included cabbage, pumpkin and corn. Their corn was roasted with the shuck on. Johnnie cake, sweetened with molasses and hominy were also common foods. The oven used for cooking their meals was made of red clay and was used under a shed outside the home.

When most Indians left this area to join the forced march over the "Trail of Tears," William Callahan avoided moving his family from their beloved mountain home by hiding in a cave. He did leave later, however, after an altercation with a white man named Jukes, during which the Indian, his violent temper aroused by curses and a false accusation, bit off Jukes' nose and one ear. Fearing that the Jukes family might retaliate by burning his home, Callahan moved to Georgia and settled near Atlanta, which was then, called Marthaville.

When Nancy was about 21 years old she sought a way to make money in order to help provide food for her many younger brothers and sisters. One of the mothers was now dead. Granny did not specify which one.

She began hauling goods from the village of Marthaville to the country stores near her home, a distance of 30 miles. Her long trips over rough roads were made in a covered, or tar-pole wagon drawn by two mules. The wagon axles were greased and the mules hitched, unhitched and fed by Nancy herself. Slaves helped her load the goods at Kyle Brothers Wholesalers and storekeepers helped her unload the cases of molasses, meat, salt, powder, lead, gun caps, shoes, dishes and wagon tires which she hauled for some 15 or 20 years. She was never robbed or molested in any way during the many trips she made alone. During this period she became engaged to one storekeeper's son, named Thomas Porter but the Civil War ended this romance. The younger Porter joined the Confederate Army and was killed in battle. Nancy remained single for over 40 more years. The war also brought death to Nancy's father, killed during the battle of Atlanta, after having fought for the Confederacy for several years.

When the Union forces first reached Atlanta, Callahan sent his daughter word not to go in for more goods, but to stay home with the children. From 30 miles away the loud roar of cannon could be clearly heard. She declared in 1928 that she would never forget the battle sound. After the burning of Atlanta, Sherman's march took him through the Indian family's cornfields, which were "in roasting ear," and Nancy assumed full responsibility for providing food for the other fatherless children. The indomitable Nancy did care for the younger children, an accomplishment, which probably gave her a great deal of satisfaction as she remembered them so many years later. "Yes, child", she told her interviewer, "my brothers and sisters are all dead." She finally married, when about 79 years old, a white man named Nelson Dollar. When he died 20 years later, this remarkable woman, who had cared for so many others, was left with no one to love and care for her.

The Strong constitution that had provided the vigor and great capacity for long endurance and hard physical work in her youth had left her alert and erect in her old age. As she reflected upon her many experiences and hardships, including three poisonous snake bites, by two copperheads and a rattler, she probably felt fully capable of caring for herself, whatever her age.

Any sadness she felt appeared to be caused by observing the changes around her. She remembered the happy days of her early childhood and the casually paced Indian ways. "My father's hut was enjoyed by all," she recalled but she noted, "Another race has taken our fields, our forests and our game. Their children now play where we once were so happy."

She also expressed her opinion about the white man's ways. "The trouble with the white race," she mused, is that they lay up so much for old age that they quit work at 50 or 60 years. When they stop working, they get out of touch with nature; all wear shoes in summer which keeps them from God's good earth; then they begin to fail, and soon they are dead."

Three years to the day from the publication date of the Progressive Farmer article about Granny Dollar, the January 28, 1931 issue of the Fort Payne Journal announced her death. A unique burial service was held at the foot of a giant mountain boulder near the cabin where Granny had spent the last years of her life.

Her only companion had been a mongrel dog she called "Buster", very old himself by animal standards, having reached the age of 20. Buster had long served as Granny's faithful guardian, ever ready to attack anyone who approached either him or his mistress. He had frightened so many people and had even bitten several children, Buster was despised by the neighbors as a mean, vicious beast but Granny had loved him.

After Granny's funeral no one wanted Buster and he was equally unwilling to have anything to do with any prospective new master or protector. When neighbors went to check on the old dog, they found him gnawing the door, his angry snarl revealing the gums which once had held dangerous teeth. After he refused to be coaxed or driven from his vigil, the mountaineers decided it would be more humane to chloroform Buster than to allow him to grieve himself to death or slowly starve. When Buster's body was buried alongside that of his master, another funeral was held with Col. Milford W. Howard, famous lawyer, congressman and author, eulogizing Granny Dollar's faithful mongrel dog.

"The Legend of Granny Dollar" is a publication of the Fort Payne Depot Museum

and can be purchased at the Museum for $3.00.

The tale of "Granny Dollar," one of the most colorful characters and rugged individualists who ever lived in the Fort Payne area, has long captured the imagination of those who have heard of this Cherokee Indian's century of varied experiences. Assuming that all the information given by Granny Dollar in an interview in 1928 is factual, these absorbing tales of her strange life certainly bear repeating; indeed, the legend of such a rare person should never die.

According to an article which appeared in the January 28, 1928 issue of the Progressive Farmer, this friendly old woman, who lived on Lookout Mountain about nine miles from Fort Payne enjoyed reminiscing and talking to visitors. She was Nancy Callahan Dollar, affectionately called "Granny" or "Grandma," though her many experiences never included that of motherhood. She said she was 101 at the time of the interview, but she remembered the early days of childhood well.

Born on Sand Mountain in Buck's Pocket eight miles east of Coffeetown, Nancy was the daughter of a Cherokee father named William Callahan and a half Cherokee Indian, half Irish mother. She enjoyed the games played by Indian children, including one called "dog and fox" and liked to pitch quoits, an activity similar to pitching horseshoes. She never attended any kind of school.

Nancy's father hunted game while the rest of the family raised corn and potatoes. On one occasion after having killed a very large deer, her father appeared to be very sad and unable to eat. The concerned mother, after persistent questioning finally elicited the reason for his distress. "I cannot eat my meat," he said. "I fear my three poor little children in South Carolina are hungry. I have a wife and three children in South Carolina and I was forced to leave them there." Nancy's mother replied, "Go and fetch them. There is room and plenty to eat."

Thus it was, that the family soon included another mother and sister and two more brothers. The Cherokees were allowed to have more than one wife and in Nancy's family, at least, there appeared to be no dissension or jealousy. She remembered that her mother appeared as happy over the new arrivals as did the children and had her big dirt oven full of baked potatoes and venison ready for the ravenous children. The two women labored together in raising the crops and caring for the family. Together, they had a total of 26 children, including three sets of triplets born to Nancy's mother.

This large family ate wild turkey, deer and fish with vegetables, which included cabbage, pumpkin and corn. Their corn was roasted with the shuck on. Johnnie cake, sweetened with molasses and hominy were also common foods. The oven used for cooking their meals was made of red clay and was used under a shed outside the home.

When most Indians left this area to join the forced march over the "Trail of Tears," William Callahan avoided moving his family from their beloved mountain home by hiding in a cave. He did leave later, however, after an altercation with a white man named Jukes, during which the Indian, his violent temper aroused by curses and a false accusation, bit off Jukes' nose and one ear. Fearing that the Jukes family might retaliate by burning his home, Callahan moved to Georgia and settled near Atlanta, which was then, called Marthaville.

When Nancy was about 21 years old she sought a way to make money in order to help provide food for her many younger brothers and sisters. One of the mothers was now dead. Granny did not specify which one.

She began hauling goods from the village of Marthaville to the country stores near her home, a distance of 30 miles. Her long trips over rough roads were made in a covered, or tar-pole wagon drawn by two mules. The wagon axles were greased and the mules hitched, unhitched and fed by Nancy herself. Slaves helped her load the goods at Kyle Brothers Wholesalers and storekeepers helped her unload the cases of molasses, meat, salt, powder, lead, gun caps, shoes, dishes and wagon tires which she hauled for some 15 or 20 years. She was never robbed or molested in any way during the many trips she made alone. During this period she became engaged to one storekeeper's son, named Thomas Porter but the Civil War ended this romance. The younger Porter joined the Confederate Army and was killed in battle. Nancy remained single for over 40 more years. The war also brought death to Nancy's father, killed during the battle of Atlanta, after having fought for the Confederacy for several years.

When the Union forces first reached Atlanta, Callahan sent his daughter word not to go in for more goods, but to stay home with the children. From 30 miles away the loud roar of cannon could be clearly heard. She declared in 1928 that she would never forget the battle sound. After the burning of Atlanta, Sherman's march took him through the Indian family's cornfields, which were "in roasting ear," and Nancy assumed full responsibility for providing food for the other fatherless children. The indomitable Nancy did care for the younger children, an accomplishment, which probably gave her a great deal of satisfaction as she remembered them so many years later. "Yes, child", she told her interviewer, "my brothers and sisters are all dead." She finally married, when about 79 years old, a white man named Nelson Dollar. When he died 20 years later, this remarkable woman, who had cared for so many others, was left with no one to love and care for her.

The Strong constitution that had provided the vigor and great capacity for long endurance and hard physical work in her youth had left her alert and erect in her old age. As she reflected upon her many experiences and hardships, including three poisonous snake bites, by two copperheads and a rattler, she probably felt fully capable of caring for herself, whatever her age.

Any sadness she felt appeared to be caused by observing the changes around her. She remembered the happy days of her early childhood and the casually paced Indian ways. "My father's hut was enjoyed by all," she recalled but she noted, "Another race has taken our fields, our forests and our game. Their children now play where we once were so happy."

She also expressed her opinion about the white man's ways. "The trouble with the white race," she mused, is that they lay up so much for old age that they quit work at 50 or 60 years. When they stop working, they get out of touch with nature; all wear shoes in summer which keeps them from God's good earth; then they begin to fail, and soon they are dead."

Three years to the day from the publication date of the Progressive Farmer article about Granny Dollar, the January 28, 1931 issue of the Fort Payne Journal announced her death. A unique burial service was held at the foot of a giant mountain boulder near the cabin where Granny had spent the last years of her life.

Her only companion had been a mongrel dog she called "Buster", very old himself by animal standards, having reached the age of 20. Buster had long served as Granny's faithful guardian, ever ready to attack anyone who approached either him or his mistress. He had frightened so many people and had even bitten several children, Buster was despised by the neighbors as a mean, vicious beast but Granny had loved him.

After Granny's funeral no one wanted Buster and he was equally unwilling to have anything to do with any prospective new master or protector. When neighbors went to check on the old dog, they found him gnawing the door, his angry snarl revealing the gums which once had held dangerous teeth. After he refused to be coaxed or driven from his vigil, the mountaineers decided it would be more humane to chloroform Buster than to allow him to grieve himself to death or slowly starve. When Buster's body was buried alongside that of his master, another funeral was held with Col. Milford W. Howard, famous lawyer, congressman and author, eulogizing Granny Dollar's faithful mongrel dog.

"The Legend of Granny Dollar" is a publication of the Fort Payne Depot Museum

and can be purchased at the Museum for $3.00.

Inscription

Erected Dec. 31, 1973