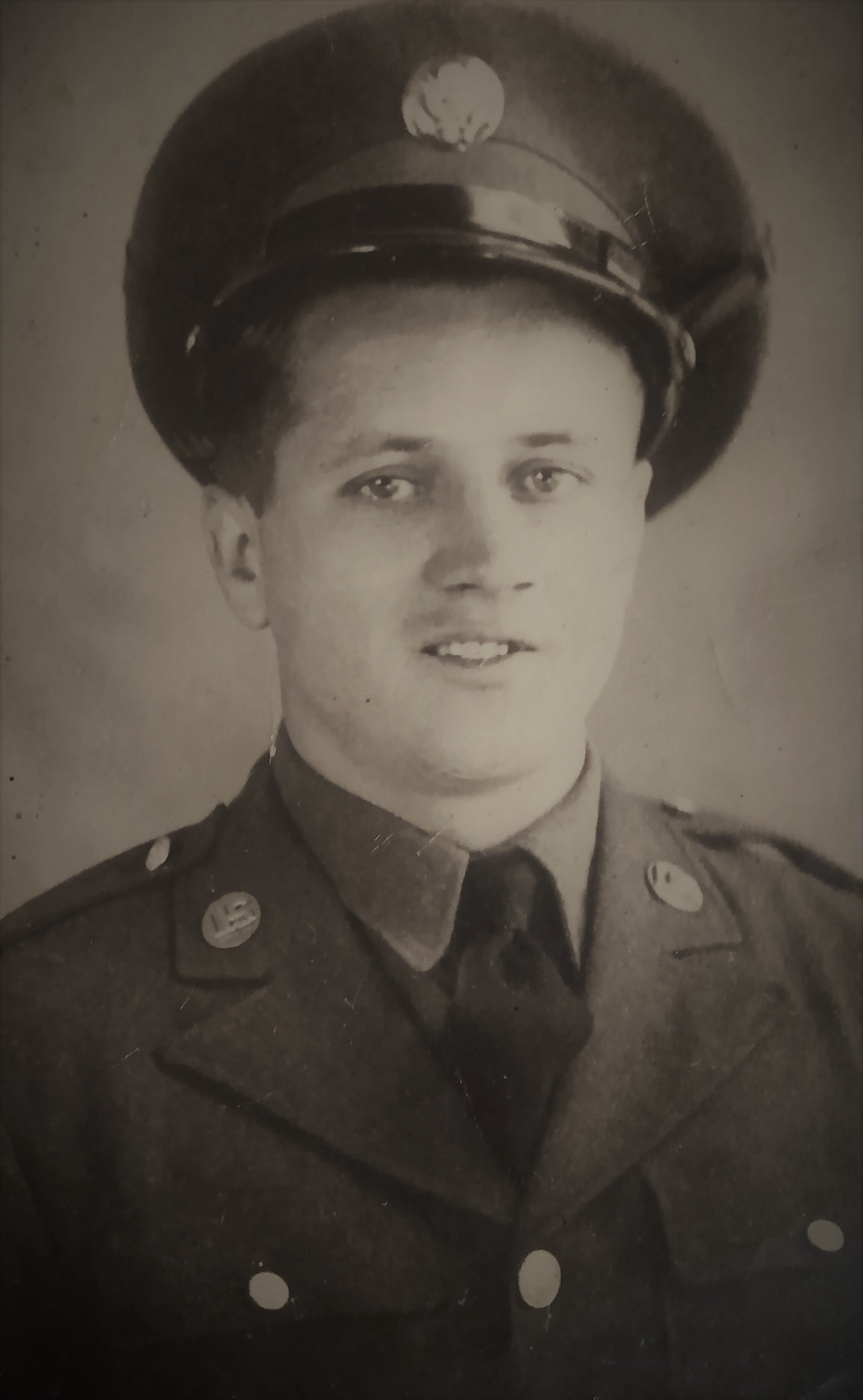

PVT, US ARMY WORLD WAR II - POW

Survivor Endured the "Unthinkable"

By Candy Long

Eighteen months before the United States declared war on Japan, Coy Daugherty left his home at the foot of Fort Lewis Mountain for Staunton to enlist in the army, telling his parents, "It looks like I'll have to help fight this war that's coming." When his country sent him to the Philippines, he had no idea that his fight would be for mere survival in unthinkable conditions. Nor did he know he would be considered by many at home an unsung war hero. Some of his experiences have been recorded here as he remembers them.

The Japanese bombed Clark Field in the Philippines on December 8, 1941 and dropped propaganda over Corregidor assuring the American forces there that they were not forgotten. True to their word, Japanese high altitude bombers and dive bombers attacked Corregidor several weeks later. These heavy air raids persisted until May when Corregidor fell to the Japanese.

"On May 2, 1942, we had taken cover in the gun emplacement. The Japanese got a direct hit with a 240 mm howitzer shells on the powder room. The concussion was so severe that a 20 ton 12 inch mortar was blasted off its mount and 10 feet of the barrel penetrated into the concrete and steel wall. The concussion threw me against a concrete wall and I was knocked unconscious and buried in the rubble. When I finally came to, someone was calling my name and asking if I was hurt. I had a big knot on my forehead and dirt and foreign matter were embedded in my forehead. The blast was so terrific that we all were in a state of shock."

Corregidor was surrendered to the Japanese that day with destruction so severe that not a single tree was left standing on the fortress.

"We were all lined up while the Japs took over. I'm telling you, you don't know what your country's flag means to you until you've seen it hauled down by an enemy you don't like one bit. As Old Glory came down that mast, I don't think there was a dry eye in the whole group. It was a day or so afterwards that we were lined up near an overpass when the Japs drove General Wainwright by. As his car sped under the overpass, we all took our hats off – ‘cause he was a swell guy – and he saluted us smartly."

Approximately 14,000 soldiers from all branches of service were captured and detained at the 92nd Garage Area, an airplane hanger about the size of a football field. For more than seven days these men were held without food and only the water they had in their canteens at the time of their capture. American soldiers were ordered to pick up the Japanese dead, stack them into piles, and burn them, an unbearable stench unforgotten by Sgt. Daugherty.

"From Corregidor we were taken by small fishing vessels to Manila, marched down Dewey Boulevard through Manila to the railroad station. We were packed like animals in the boxcars and the doors were locked shut. The odor was terrible and the heat so terrific that we almost suffocated – some did. We were taken to Cabanatuan POW camp where conditions were deplorable – 40 to 50 men were dying per day. There was one young man out of my outfit in this camp – a boy I had put through boot camp. He came to me and told me that he could not eat the filthy rice. I pointed to a hill where men were being carried to mass graves and told him that if he didn't eat that rice, he would end up on that hill. Less than a week later that boy died of starvation. I saw three POW's forced to dig their own graves then stand by them – the Japanese shot them and they fell into the graves they had dug. I knew that I had to get out of this camp. The Japs asked for a 150 man detail and I volunteered. We did not know what we were volunteering for, but nothing could be worse than the Cabanatuan POW camp. We were taken to Bilibid Prison in Manila then on to Palawan. Conditions were poor but we did get a little rice (barely enough to keep us alive) and on occasions we would get sweet potato vine soup."

The Japanese's plan was for this detail of American POW's to build an airstrip in the jungle. It was sometime later when another 150 man detail arrived to help with the task. Using only picks, shovels, chisels, and wheelbarrows, these men had to level land, dig around coconut trees and cut the roots, and chisel coral rock even with ground level. "We built a fairly good air strip considering we had barely nothing to work with."

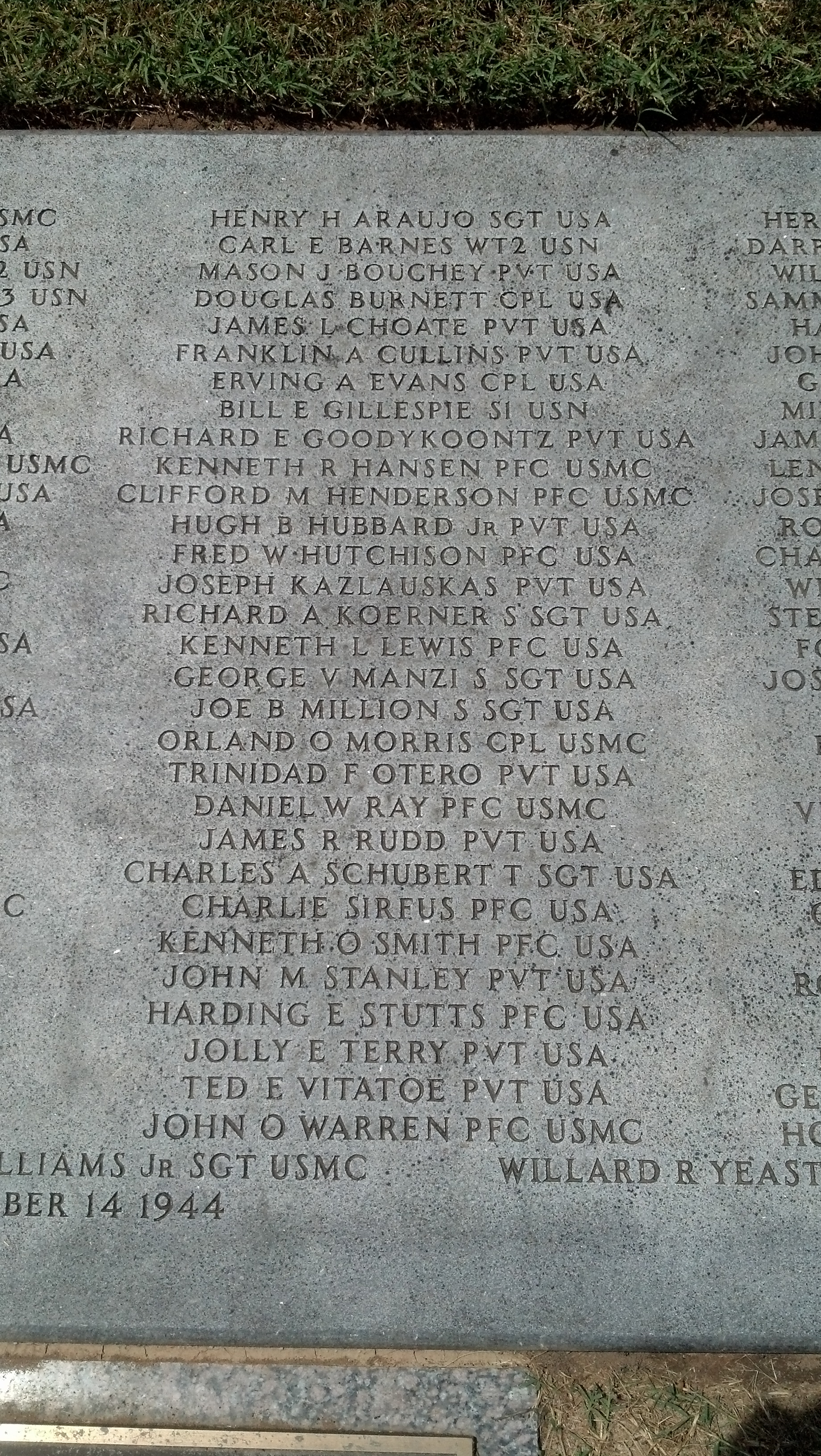

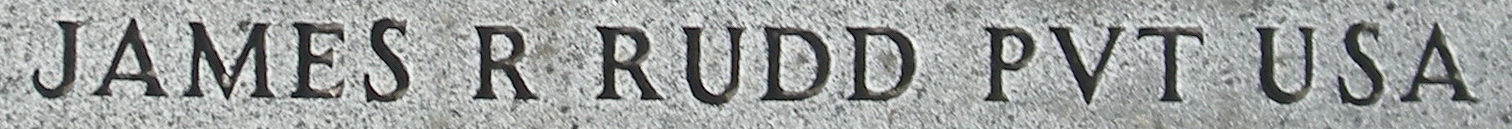

American forces began bombing the Philippines in preparation to retake the islands. In September 1944, 150 men were loaded onto "Hell Ships" en route to Japan while the others remained on Palawan including Rollie Rudd, Sgt. Daugherty's best friend.

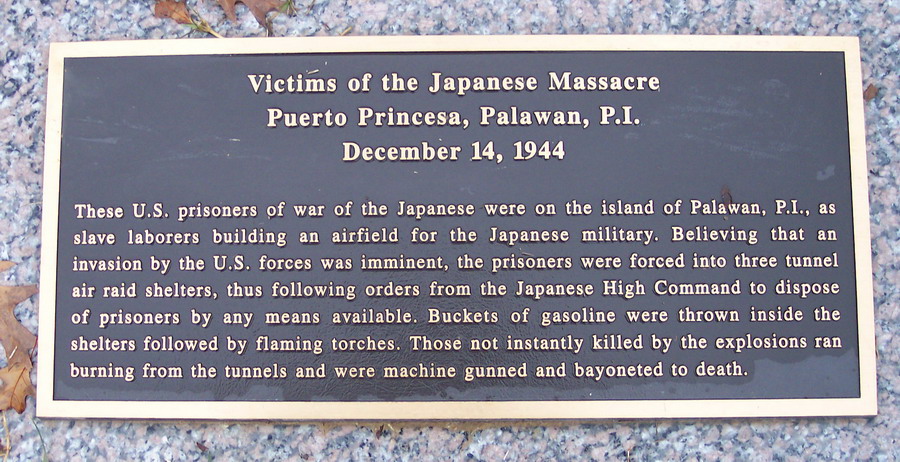

"There is something I need to tell you about Palawan," Sgt. Daugherty said in almost a whisper. "On December 14th 1944, the detail went out to work but was recalled and given the explanation that an air raid was expected. The POW's were herded into bomb shelters and strictly ordered that no matter what happened they were not to even lift their heads out of these trenches. Gasoline was poured in the shelters and ignited. Those men who tried to escape the inferno were either shot or bayoneted to death. Rollie Rudd was one of those men."

Of the 150 American POW's that remained on Palawan, 139 men died in that massacre. One of Sgt. Daugherty's buddies was one of the eleven men able to escape and swim the five miles to survival. He told him later, "As I was swimming, I was praying; not for myself but for one man to survive to be able to tell the story." A detailed account of the story indeed was told in the national bestseller Ghost Soldiers researched and written by Hampton Sides.

On or about September 30th, 700 men including Sgt. Daugherty were ordered into the hole of an unmarked, filthy cargo ship previously used to transport cattle. Some of the prisoners made hammocks out of blankets tied to the bulkheads which made enough room for those remaining below to sit or squat.

"As night drew on, I dropped into a sleep and was awakened by a nightmare – I felt as if I were suffocating. I did not go back to sleep that night as I was afraid to. When morning dawned, I was leaning against a dead man. I did not know him nor what caused his death. After this incident, I tied my blanket up on the ribs of the ship and this is where I stayed for the remainder of the 39 day voyage."

"I received about a handful of unseasoned rice, once a day. It was dirty and

contained bugs but I was so hungry that I ate it. I may have received a gallon of water during the entire trip. For three days, I had no water until a buddy gave me a drink of his. There were no toilet facilities for the POW's on this ship; a bucket was passed down on a rope and there was never one available when needed. When the bucket was pulled up, the POW's were splattered with its contents. The conditions were so deplorable that it is hard for anyone to believe what actually happened."

A haunting "pinging sound" could be heard occasionally during the voyage. It was of little concern until one of the POW's, a submarine technician, explained just what they were hearing. American subs had detected the convoy of about 10 Japanese vessels and were "pinging" them with radar to determine how large the ships were and what was being carried.

"It was so hot in the hold of that ship that at times I wished the ship would be blown to pieces so I could feel the water and get a breath of fresh air before I died."

Whether or not the American subs knew the ship carried American POW's was never determined. However, eight of the ten Japanese vessels were lost and the two remaining turned and headed for Hong Kong, China. From there, they were taken to Formosa.

"When I tried to walk I could see what those 39 days of hanging in a hammock did to me. I lost over 50 pounds on this trip and was so weak I could hardly walk. When I tried to run, I would fall.

"Once again, I worked as a slave laborer for two months loading rocks on freight cars. I contracted malaria on Formosa. Some POW's contracted a disease which caused severe headaches that almost run them crazy. Some died from this disease. I also had beriberi. My feet and legs swelled so bad, I could not walk on them. We received no medication for our illnesses."

After two months at Formosa, Sgt. Daugherty and other POW's were put on another ship, the Sanko Maru, and sent to Japan.

"The living conditions aboard this ship were slightly better though the rats and lice were terrible. I was awakened at night by rats scampering over me. We picked lice off of each other."

The ship landed in Moji, Japan on February 11, 1945 and the men were taken to a prison camp in Northern Honshu where they stayed for only a few days before being sent to Sendai POW 111-B Hosokura. The men were once again forced to do slave labor at the Mitsubishi Mine and Metal Company.

"We were issued no clothes up to this time and when we arrived in Japan in summer khakis, the temperature was below freezing – we almost froze! In Moju, Japan, I was issued an old brown overcoat that looked like burlap with no lining. All we had for shoes was old Japanese tennis shoes. We worked in water sometimes up to our knees in these mines. The Japs would blast while we were in the tunnels. We breathed all that dust and dirt from the lead and zinc ore. One POW lost a leg to lead poisoning. The ground was so frozen that we couldn't even dig a grave for a fellow POW who died. We slept on the floor in a wooden building with no heat. If anyone picked up a chip of wood on the way back to the building from the mines, they got hit over the head with a stick. The only way to keep from freezing was to sleep close to each other. We thought we would surely freeze."

On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Hiroshima, Japan destroying five square miles of the city and killing approximately 100,000 people. After no response came from the Japanese, a second bomb was dropped over Nagasaki killing nearly 40,000 people.

"We knew that something had happened, we just didn't know what. A Japanese officer came in and pulled up a box – the Japs always spoke to us POW's on a box on account that most of them were shorter than we were – and he began to speak. This is what he said, ‘The American's dropped big bomb on a town. No more town. We thinking. The Americans dropped another big bomb on another town. No more town. We surrender'. Just before we were liberated, I had boils all over me. Colonel Gaskill, our camp doctor gave me six shots of penicillin that had been dropped by the Americans into our POW camp. I had also come down with Malaria in this camp. I don't think I could have lived another six months in a Japanese POW camp."

Sgt. Daugherty was flown from Okinawa to the Philippines where a hospital ship awaited to take the surviving POW's back to the states.

"All that time I was a Japanese POW, I received one letter and it was from her," Coy Daugherty said pointing to his wife. She shrugged and sweetly replied, "We wrote to everybody." Six months after he stepped off the train onto hometown soil, he married the younger sister of the girls he courted in his youth.

After the war, Coy Daugherty and his wife visited the parents of Rollie Rudd. "I needed to tell them what happened to their son – my best friend.

"I still have nightmares. They will follow me to my grave. I often wonder why I was spared and some of my best friends were killed or died in prison camps. I think of the guys we left on Palawan – we were closer than brothers – they were within several months of being liberated when they were massacred."

PVT, US ARMY WORLD WAR II - POW

Survivor Endured the "Unthinkable"

By Candy Long

Eighteen months before the United States declared war on Japan, Coy Daugherty left his home at the foot of Fort Lewis Mountain for Staunton to enlist in the army, telling his parents, "It looks like I'll have to help fight this war that's coming." When his country sent him to the Philippines, he had no idea that his fight would be for mere survival in unthinkable conditions. Nor did he know he would be considered by many at home an unsung war hero. Some of his experiences have been recorded here as he remembers them.

The Japanese bombed Clark Field in the Philippines on December 8, 1941 and dropped propaganda over Corregidor assuring the American forces there that they were not forgotten. True to their word, Japanese high altitude bombers and dive bombers attacked Corregidor several weeks later. These heavy air raids persisted until May when Corregidor fell to the Japanese.

"On May 2, 1942, we had taken cover in the gun emplacement. The Japanese got a direct hit with a 240 mm howitzer shells on the powder room. The concussion was so severe that a 20 ton 12 inch mortar was blasted off its mount and 10 feet of the barrel penetrated into the concrete and steel wall. The concussion threw me against a concrete wall and I was knocked unconscious and buried in the rubble. When I finally came to, someone was calling my name and asking if I was hurt. I had a big knot on my forehead and dirt and foreign matter were embedded in my forehead. The blast was so terrific that we all were in a state of shock."

Corregidor was surrendered to the Japanese that day with destruction so severe that not a single tree was left standing on the fortress.

"We were all lined up while the Japs took over. I'm telling you, you don't know what your country's flag means to you until you've seen it hauled down by an enemy you don't like one bit. As Old Glory came down that mast, I don't think there was a dry eye in the whole group. It was a day or so afterwards that we were lined up near an overpass when the Japs drove General Wainwright by. As his car sped under the overpass, we all took our hats off – ‘cause he was a swell guy – and he saluted us smartly."

Approximately 14,000 soldiers from all branches of service were captured and detained at the 92nd Garage Area, an airplane hanger about the size of a football field. For more than seven days these men were held without food and only the water they had in their canteens at the time of their capture. American soldiers were ordered to pick up the Japanese dead, stack them into piles, and burn them, an unbearable stench unforgotten by Sgt. Daugherty.

"From Corregidor we were taken by small fishing vessels to Manila, marched down Dewey Boulevard through Manila to the railroad station. We were packed like animals in the boxcars and the doors were locked shut. The odor was terrible and the heat so terrific that we almost suffocated – some did. We were taken to Cabanatuan POW camp where conditions were deplorable – 40 to 50 men were dying per day. There was one young man out of my outfit in this camp – a boy I had put through boot camp. He came to me and told me that he could not eat the filthy rice. I pointed to a hill where men were being carried to mass graves and told him that if he didn't eat that rice, he would end up on that hill. Less than a week later that boy died of starvation. I saw three POW's forced to dig their own graves then stand by them – the Japanese shot them and they fell into the graves they had dug. I knew that I had to get out of this camp. The Japs asked for a 150 man detail and I volunteered. We did not know what we were volunteering for, but nothing could be worse than the Cabanatuan POW camp. We were taken to Bilibid Prison in Manila then on to Palawan. Conditions were poor but we did get a little rice (barely enough to keep us alive) and on occasions we would get sweet potato vine soup."

The Japanese's plan was for this detail of American POW's to build an airstrip in the jungle. It was sometime later when another 150 man detail arrived to help with the task. Using only picks, shovels, chisels, and wheelbarrows, these men had to level land, dig around coconut trees and cut the roots, and chisel coral rock even with ground level. "We built a fairly good air strip considering we had barely nothing to work with."

American forces began bombing the Philippines in preparation to retake the islands. In September 1944, 150 men were loaded onto "Hell Ships" en route to Japan while the others remained on Palawan including Rollie Rudd, Sgt. Daugherty's best friend.

"There is something I need to tell you about Palawan," Sgt. Daugherty said in almost a whisper. "On December 14th 1944, the detail went out to work but was recalled and given the explanation that an air raid was expected. The POW's were herded into bomb shelters and strictly ordered that no matter what happened they were not to even lift their heads out of these trenches. Gasoline was poured in the shelters and ignited. Those men who tried to escape the inferno were either shot or bayoneted to death. Rollie Rudd was one of those men."

Of the 150 American POW's that remained on Palawan, 139 men died in that massacre. One of Sgt. Daugherty's buddies was one of the eleven men able to escape and swim the five miles to survival. He told him later, "As I was swimming, I was praying; not for myself but for one man to survive to be able to tell the story." A detailed account of the story indeed was told in the national bestseller Ghost Soldiers researched and written by Hampton Sides.

On or about September 30th, 700 men including Sgt. Daugherty were ordered into the hole of an unmarked, filthy cargo ship previously used to transport cattle. Some of the prisoners made hammocks out of blankets tied to the bulkheads which made enough room for those remaining below to sit or squat.

"As night drew on, I dropped into a sleep and was awakened by a nightmare – I felt as if I were suffocating. I did not go back to sleep that night as I was afraid to. When morning dawned, I was leaning against a dead man. I did not know him nor what caused his death. After this incident, I tied my blanket up on the ribs of the ship and this is where I stayed for the remainder of the 39 day voyage."

"I received about a handful of unseasoned rice, once a day. It was dirty and

contained bugs but I was so hungry that I ate it. I may have received a gallon of water during the entire trip. For three days, I had no water until a buddy gave me a drink of his. There were no toilet facilities for the POW's on this ship; a bucket was passed down on a rope and there was never one available when needed. When the bucket was pulled up, the POW's were splattered with its contents. The conditions were so deplorable that it is hard for anyone to believe what actually happened."

A haunting "pinging sound" could be heard occasionally during the voyage. It was of little concern until one of the POW's, a submarine technician, explained just what they were hearing. American subs had detected the convoy of about 10 Japanese vessels and were "pinging" them with radar to determine how large the ships were and what was being carried.

"It was so hot in the hold of that ship that at times I wished the ship would be blown to pieces so I could feel the water and get a breath of fresh air before I died."

Whether or not the American subs knew the ship carried American POW's was never determined. However, eight of the ten Japanese vessels were lost and the two remaining turned and headed for Hong Kong, China. From there, they were taken to Formosa.

"When I tried to walk I could see what those 39 days of hanging in a hammock did to me. I lost over 50 pounds on this trip and was so weak I could hardly walk. When I tried to run, I would fall.

"Once again, I worked as a slave laborer for two months loading rocks on freight cars. I contracted malaria on Formosa. Some POW's contracted a disease which caused severe headaches that almost run them crazy. Some died from this disease. I also had beriberi. My feet and legs swelled so bad, I could not walk on them. We received no medication for our illnesses."

After two months at Formosa, Sgt. Daugherty and other POW's were put on another ship, the Sanko Maru, and sent to Japan.

"The living conditions aboard this ship were slightly better though the rats and lice were terrible. I was awakened at night by rats scampering over me. We picked lice off of each other."

The ship landed in Moji, Japan on February 11, 1945 and the men were taken to a prison camp in Northern Honshu where they stayed for only a few days before being sent to Sendai POW 111-B Hosokura. The men were once again forced to do slave labor at the Mitsubishi Mine and Metal Company.

"We were issued no clothes up to this time and when we arrived in Japan in summer khakis, the temperature was below freezing – we almost froze! In Moju, Japan, I was issued an old brown overcoat that looked like burlap with no lining. All we had for shoes was old Japanese tennis shoes. We worked in water sometimes up to our knees in these mines. The Japs would blast while we were in the tunnels. We breathed all that dust and dirt from the lead and zinc ore. One POW lost a leg to lead poisoning. The ground was so frozen that we couldn't even dig a grave for a fellow POW who died. We slept on the floor in a wooden building with no heat. If anyone picked up a chip of wood on the way back to the building from the mines, they got hit over the head with a stick. The only way to keep from freezing was to sleep close to each other. We thought we would surely freeze."

On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Hiroshima, Japan destroying five square miles of the city and killing approximately 100,000 people. After no response came from the Japanese, a second bomb was dropped over Nagasaki killing nearly 40,000 people.

"We knew that something had happened, we just didn't know what. A Japanese officer came in and pulled up a box – the Japs always spoke to us POW's on a box on account that most of them were shorter than we were – and he began to speak. This is what he said, ‘The American's dropped big bomb on a town. No more town. We thinking. The Americans dropped another big bomb on another town. No more town. We surrender'. Just before we were liberated, I had boils all over me. Colonel Gaskill, our camp doctor gave me six shots of penicillin that had been dropped by the Americans into our POW camp. I had also come down with Malaria in this camp. I don't think I could have lived another six months in a Japanese POW camp."

Sgt. Daugherty was flown from Okinawa to the Philippines where a hospital ship awaited to take the surviving POW's back to the states.

"All that time I was a Japanese POW, I received one letter and it was from her," Coy Daugherty said pointing to his wife. She shrugged and sweetly replied, "We wrote to everybody." Six months after he stepped off the train onto hometown soil, he married the younger sister of the girls he courted in his youth.

After the war, Coy Daugherty and his wife visited the parents of Rollie Rudd. "I needed to tell them what happened to their son – my best friend.

"I still have nightmares. They will follow me to my grave. I often wonder why I was spared and some of my best friends were killed or died in prison camps. I think of the guys we left on Palawan – we were closer than brothers – they were within several months of being liberated when they were massacred."

Inscription

PVT, US ARMY WORLD WAR II

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement