Death Claims Aged Resident After Illness Of Four Hours Duration

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

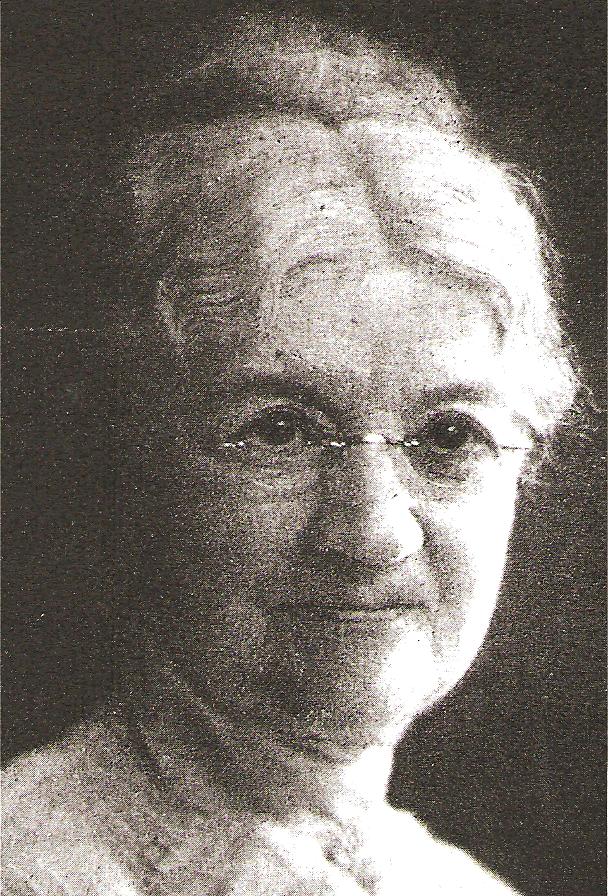

Mrs. Liberty Augustus Clutz, widow of Dr. Jacob A. Clutz, formerly a professor of the Lutheran Theological seminary here, died at 12:30 o'clock this afternoon at the home of her son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. Mark K. Eckert, Springs avenue. She was 82 years of age.

Mrs. Clutz arouse this morning in usual health, and was taken ill about 9 o'clock, failing rapidly until the end this afternoon. Death was caused by cerebral hemorrhage.

NATIVE OF COUNTY

A daughter of the late Jacob S. and Sara (Diehl) Hollinger, Mrs. Clutz was born in Heidlersburg, but spent the greater part of life in Gettysburg.

She was living in Gettysburg in a house on the site of the Lincoln school building, York street, during the battles here in 1863, and two years ago, she had published her personal recollections of those stirring times.

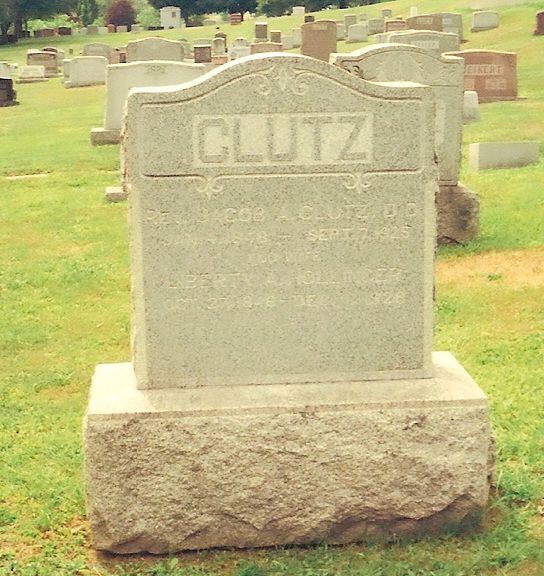

She was married to Doctor Clutz in 1872. He died at Stockholm, Sweden, September 7, 1925, while attending a Lutheran convention, after being run down by an automobile truck.

ACTIVE CHURCH WORKER

Mrs. Clutz was a life-long member of Christ Lutheran Church, and always took an active part in work there.

Surviving are two daughters, Mrs. Eckert, with whom she resided since the death of her husband; Mrs. Julia T. Peters, New Cumberland; three sons, Dr. Frank H. Clutz, Broadway; Ralph R. Clutz Bendena, Kansas; and one brother, J.A. Hollinger, Hagerstown; one sister, Mrs. Annie H. Nelson, Chambersburg, and by ten grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements will be announced later.

The Gettysburg Times

{Gettysburg, Pennsylvania}

December 1 1928

MRS. CLUTZ IS BURIED TODAY

Funeral services for Mrs. Liberty Augustus Clutz, widow of Dr. Jacob A. Clutz, who died last Saturday afternoon, were held this afternoon at the home of her son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. Mark K. Eckert, Springs avennue. The services were in charge of the pastor Rev. Dr. Luther Kulhman, acting pastor of Christ Lutheran church, assisted by the Rev. Dr. A.R. Wentz, of the seminary. The sermon was preached by the Rev. Dr. A.E. Wagner, Hallam, former pastor at Christ Lutheran. Internment was private in Evergreen cemetery.

Pallbearers were, Dr. Albert Billheimer, J.L. Burgoon, Harry Snyder, Dr. J. E. Musselman, Dr. Raymond Stamm and James Cairns.

The Gettysburg Times

{Gettysburg, Pennsylvania}

December 5 1928

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

www3.gettysburg.edu/~jrudy/History/The Battle of...

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG (pg. 166-178)

By Mrs. Jacob A. Clutz

(Liberty Augustus Hollinger)

Edited by Elsie Singmaster, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

LIBERTY AUGUSTUS HOLLINGER was sixteen years old at the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, the eldest of a family of four girls and one boy, living with their parents at the eastern end of the pleasant, tree-shaded town. Besides the Lutheran Theological Seminary and Pennsylvania (now Gettysburg) College, the town contained an academy for boys and two private schools for girls. Its chief industry was the manufacture of carriages in which about two hundred men were engaged.

Mrs. Clutz speaks with naive admiration of the beauty of her young sister. She herself retained until her death at the age of eighty-one the characteristic charm of her family. She was married to graduate of the seminary, Jacob A. Clutz, who, after serving various parishes and being president of Midland College at Atchinson, Kansas, returned to Gettysburg as pastor of St. James Lutheran Church. He was afterwards a professor at the Lutheran Theological Seminary. In Gettysburg, her large family married and gone, Mrs. Glutz was happy in her garden, her friends and her books. She never ceased to believe the Civil War was a sad necessity; she always revered Abraham Lincoln.

In attendance at a religious convocation in Sweden, Dr. Clutz was struck by a car are fatally injured. With the same fortitude with which she had ministered to the wounded in her girlhood, Mrs. Clutz endured this overwhelming shock during the few years of life which remained.

Her reminiscences were written in 1925, sixty-two years after the battle. They are remarkable only as any simple, vivid narrative is remarkable. They are especially interesting because they show calmness and efficiency with which the citizens of Gettysburg, even children, met the most terrible of disasters.

{Elsie Singmaster}

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

My Children, and other members of our family, have often expressed a wish that I would make some permanent record of any recollections of the Battle of Gettyburg. So many years have passed that many things have entirely escaped my memory. But this year, 1925, the anniversary of the battle has happened to fall again on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. In imagination I live it all over almost as though it were just occurring. So many vivid pictures crowd my mind and fill my soul, that I hesitate to try to describe them as they occurred. But I will do the best I can.

At the time of the battle I was a young girl of sixteen. We were living on York street where the present high school building stands. Our house, a roomy brick one, stood in the center of a large plot of ground between the York Pike, which was the continuation of York Street, and what was known as the Bonneauvville, or Hanover Road, now Hanover Street. there were two roads, and a few opposite on the other side.

There was excitement in Gettysburg for some days before the battle, especially during the preceeding week when a detachment of Confederate cavalry entered the town and passed on down the Baltimore Pike. There was great commotion on the morning of Wednesday, July 1st, when the report spread from door to door that the enemy was coming in force. We could also hear an occasional boom of cannon west of town. My father was at the warehouse down along the railroad, on the corner of Stratton Street, where he was engaged in the grain and produce business. My brother Gussie, then a little lad of about 5 years, was eager to go to see father because he wanted to show him his first waist and breeches. I decided to go with him to please him, and also to hear what father thought about the situation. He did not seem in the least excited, and advised a little calm waiting for further developments. When I got home and turned into our gate I knew that the excitement was increasing. Many of our neighbors left their homes only to encounter greater danger elsewhere. Meanwhile, their houses were ransacked by the Confederates who took possession of most of the houses they found deserted and helped themselves to whatever they wanted, especially food.

While we were deliberating what would be best to do, two wounded Union officers came up, and a captain with a bullet in his neck, and the other a lieutenant with a bullet in his wrist. Both were suffering greatly. We appealed to them for advice, and they immediately asked about the cellar. The heartily agreed that it would be a safe place during the battle. We found mother lying in a faint from the excitment, and the officers first carried a rocking chair to the cellar, then mother herself. They then said that they must hurry off or they would be taken prisoners by "Johnny Reb."

In a little while General Howard's troops of the Eleventh Corps retreated through the town to Cemetery Hill past our house. They were closely followed by the Confederate troops and as e saw the gray uniforms, we thought with fear of the two kind officers who had delayed their departure in order to give us help and advice. We were very happy to hear from them after the battle that they had reached the Union lines safely, and later that they had recovered from their wounds. As the two lines of soldiers ran past, firing as they went, we watched them through the cellar windows. Oh! What horror filled our breasts as we gazed upon their bayonets glistening in the sun, and heard the deafening roar of musketry! Mother was roused to consciousness by the terrific explosions and murmured over and over, "have they shot at the town?"

Soon we heard that General Reynolds had fallen in the grove west o the seminary, now known as "Reynolds Woods." We felt then that we were indeed in the midst of a serious stife. General Howard's men had sought the hills south of the town, both for greater safety and to prepare for further battle in a stronger position. The Confederates filled the town. They were appearing everywhere on the streets and taking possession of our neighbor's houses that had been abandoned. After making biscuits in a house across the street several called to Julia, my sister, who was on our balcony, and asked for butter for their biscuits. She saucily answered, "If you are hungry you can eat them as they are." They laughed and went back into the house.

Some of them rode into our yard and demanded the keys to the warehouse from father, who had locked it and come home when our men retreated. He refused to give them up, and they said calmly that of course they would get in. "Well," said father, "if you do I cannot prevent it, but I am not inviting you by giving you my keys." They then requested father to allow them to come into the house, and asked whether we would not cook and bake for them. Father again said "No," and when they insisted Julia came to the rescue. When she stepped out of the cellar and said that is would be impossible for us to do so, it was as though a vision had appeared. Without another word they quickly rode out of the yard. She was at that time between fourteen and fifteen years old, a very attractive child, with dark brown eyes and beautiful brown curls, who always seemed to attract and impress strangers.

The same men came a number of times and wanted to take our horse and cow. Father always told them that the horse was too old to be of any use to them, and for the time being they left the horse and the cow. There was a flourishing patch of corn back of the house near the barn. This was a temptation for their horses, but father simply told them that they could not use it, and wonderful to tell they never did. I do not why they maintained such a gentlemanly demeanor unless it was father's silvery head that awakened their respect. He was not yet forty-three years old, but his hair and beard had turned gray early and were as white as snow, making him look quite venerable. Of course the Confederates, forced the locks of the warehouse and took what they wanted and then ruined everything else. They opened the spigots of the molasses barrels and allowed the molasses to run over the floor. They scattered the salt and sugar on the floor also, and everything else that was accessible.

Finally the also took our horse when they retreated on Saturday, but I suppose they soon discovered that father had told them the truth when he said it was too old for service. At any rate they did not take it very far, and a few days later we heard that it was at Hanover. Father went and proved his property and brought it home no worse for the capture and little trip. The animal had been used many years as a draft horse at the warehouse, and was well known all over the town and through the surrounding country.

We stayed in our cellar most of the time during thee three days of battle. How glad we were for such a safe retreat from all harm and danger! A few bullets struck the cellar doors, and occasionally we could hear them strike the brick walls of the house, but we felt perfectly safe. There was a large wheat-field south of our house on the Culp farm, ripe and ready for harvest, and it seemed to be full of Union sharpshooters. We could see them pop up and fire when any of the Confederates, especially officers rode by. We could see them in the trees and beyond also. When father left the cellar to feed the chickens or to milk the cow, the bullets

flew about him. Finally , he spoke to the sharpshooters about it. An officer said, "Why man, take off that gray suit; they think you are "Johnny Reb". He put on a black suit and had no further trouble. We ate cold dinners in the cellar, and sometimes breakfast too. One morning the cannon planted around our house began to shake the house with their unearthly explosions before we were ready to descend. In the evenings, after the firing ceased, we ventured up into the kitchen to cook a hot meal, and we slept upstairs every night.

Such was our life for three days, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. On Saturday morning we went downstairs to try to get a little breakfast and soon realized that all was quiet there. We ventured out to look around. The few Confederates seemed to be either wounded or were stragglers. The battle was ended and it was not long before our own Union soldiers began to appear. A number of them came to the house, so tired and hungry that mother invited them in, and began to cut bread for them. She spread he bread with butter and then set out a crock of apple-butter, telling them to help themselves. They did so in a hurry and declared that is was "the best stuff they ever ate." Later in the day father found a number of worn and bedraggled Union soldiers in the barn. We fed them also, and they became very friendly. Among them was a German who fell in love with Julia. He would say to her, "Now, Yulie, you say Chorge, no more drink, and Chorge no more drink. He would also repeat the saying that was common among the Germans of the Eleventh Corps. "I fight mit Sigel, nut I runs mit Howard." There were two young soldiers among these who came to visit us a number of times after the war was over. One was a Dr. Agnew, and the other a Mfr. Wallace.

There was a great deal of rain after the battle. Some thought that is was because of the heavy cannonading and the explosion of so much ammunition. How we suffered from the awful, awful stench coming from the dead horses and even the dead and wounded soldiers from both armies who were still unburied or uncared for! Father felt that he must help out on the field. Hearsick and soul-sick and with aching back he served the terribly wounded with the one thing they clamored for-water, water, until he was ready to drop from exhaustion.

One of the most interesting incidents in our experiences was the appearance of General Lee and his staff in front of our house on the evening of the first day of the battle. I very well remember his face and striking appearance as he sat on his splendid was-horse, "Traveller." they were in front of our house for sometime, while General Lee was observing, through his field glasses the hills south of the town on which General Howard had taken refuge, and where now the whole Army if the Potomac was taking its stand to give further battle to the Army of Northern Virginia. After a long and careful examination he took his glasses down and I heard him say to the officers near him something like this: "Those hills all around are natural fortresses. Wonderful! Wonderful! It will be very difficult to capture them or dislodge the troops holding them."

There was a handsome young officer on GeneraL lee's staff who backed his horse up quite close to the gate where Julia and I were standing. He presented a very striking figure, mounted on a beautiful sorrel with a red sash passed over his right shoulder and fastened at his waist in a knot from which the fringe fell over his knee. I think his name was Breckenridge. He seemed to give no heed to what his commander was saying about the wonderful hills on which our men were entrenched. I heard much of what they were saying.

I also heard much that was being discussed right by me. Julia was telling the young officer how our troops were coming to Gettysburg from all points, and that soon there would be a formidable army gathered which they could not withstand. He looked at her quizzically and seemed amused, but he made no unkind or harsh reply. How much he believed we could not tell. Father kept telling the Confederates on every opportunity that they would soon be wiped out, as our men were coming in great numbers from all directions. What seemed to dishearten them more than anything else was that there seemed to be so large a number of able-bodied men left on the farms and in the towns for service in any emergency. All their men, young and old, were in the ranks, with no reserves left. They realized that the North could continue the war indefinitely,while they had about exhausted their resources.

The second day of the battle many wounded were carried through our yard on stretchers. Sometimes blood dripping through the stretchers, and their faces were pale as death. Once in a while a man was entirely covered, too badly wounded to be seen. Some were able to help themselves and came limping through with the blood oozing from their wounds. One very youthful soldier in a blue uniform hobbled into the yard with a wound in his foot. The blood soaking his shoe, and mother urged him to go to a hospital and have his shoe removed and the wound dressed as soon as possible, as his foot would swell so that the show could not be removed. We could not tell whether those on the stretchers were Confederate or Union soldiers, but I suppose that most of them were Confederates, as they would likely care for their own wounded first.

On the evening of Thursday, the second day, a number of Confederates came into the yard and asked father to get them supper. He said he did not think that we could feed them. Just then Julia came out of the cellar and stood on the ssteps which led up into the yard outside the house. The minute they saw her their attitude entirely changed. They became very courteous and politely asked us girls to sing for them. Julia was very patriotic and told them we would not sing to please Confederates, but that possibly our boys in blue might hear us and be cheered. So we sang a number of our own Union war songs with which we were familiar. Each time the Confederates would respond with one of their songs. Presently an officer rode into the yard and said to one of the men, "Cap, you'd better be careful about these songs." The captain answered, "Why thats all right. They sing their battle songs, and hen we sing ours." They asked us whether we had an instrument, and they wanted to come into the house and have a pleasant social time. But father and mother would not consent.

On Saturday afternoon a Confederate surgeon came into the yard and lifting his hat very politely, asked mother if he might sit on the porch and rest. He was very tall and fine-looking, a perfect gentleman both in appearance and manners. He appeared tired and worn. My sister Annie, who was then about nine years old, was standing near him and he took her hand and asked mother if he might hold her on his knee. Mother and I were busy getting supper, and when i was ready she invited him to eat with us. He declined, very polietly, saying that he could not possibly eat anything as he was too weary and heartsick from amputating limbs all day. We could see blood-stains on his boots. There was an emergency hospital in a carpenter's shop not far from our house. The carpenter's bench was used as a operating table, and my sister Bertie, who had gone there several times said that there was a big pile of legs and arms outside the window. She was about seven at this time. No doubt it was in this shop that he had been operating. We did not learn his name.

When hospitals were better established we carried dainties to the wounded and dying of both armies, nearly every day. Mother, especially, was tireless in her willingness to bake and work and to carry cheer and comfort to the suffering soldiers. Of course other women were similarly engaged, both women of Gettysburg and many visitors who cam to minister to the wounded. One of the familiar figures on the streets in those days that interested us very much was Dr. Mary Walker. Her low silk hat, with bloomers, and a man's coat and collar, seemed invariably to call forth a laugh or a yell from the young boys, and many a smile and shrug from the older people.

In one of my mother's visits to the hospitals she found a very young Confederate soldier, a mere boy, who was fatally wounded. He seemed so happy to see her, and begged her to come again. He said he loved to look at her because she reminded him of his mother. But, alas! The next time she went to see him she found his cot empty. Mother also visited a young Union soldier by the name of Ira Sparry who lay badly wounded in the Reformed Church. She was much pleased with his general appearance and manners. He seemed to be getting along all right, and when he learned that his wife was coming to see him he was happy. Their home was in Portland, Maine. She finally arrived and came to our house, but too late to see her husband. He had suddenly taken a turn for the worse, and had died and was buried the day before she reached Gettysburg.

This woman came to Gettysburg with the father of a wounded boy who was at our house. The boy's first name was Paul; I do not remember his other name. His right arm had been amputated at the shoulder, and it was my duty to dress the wound every morning and evening. How still he used to hold while I thoroughly cleaned it! His father took him home, and we heard later that though the wound had healed he died from the effects of it. While he was at our house he was so painfully nervous from the pain and shock that he had to have an anodyne every evening on retiring so as to get some sleep and rest.

Still another interesting case was that of a young soldier whom we used to visit in the general hospital which was established in a grove along the York Pike, now the Lincoln Highway. The boy's left foot had been amputated, but he was always very jolly. Three or four years ago he came back to see the battlefield for the first time and he came out to our house at the seminary with Mr. Taughinbaugh, at whose house he was lodging. He asked whether my name had been Liberty Hollinger, and he recalled my visits to the hospital. At first I could not remember him, but after a little conversation it all came back to me again very clearly.

On the afternoon of the first day's fight, when our men were falling back, a very young Union soldier came into our yard, and asked mother to keep his blanket and knapsack for him. He said he was not well and that they were too heavy for him to carry. He told her that if he never got back for them she should keep them. We never heard from him again.

One day Julia and I went out to the seminary's building to see a wounded Confederate officer, Major General Trimble. I do not know how we came to do this, but I remember that we gave him a bouquet of flowers, and that he and his orderly were very polite and kind to us. I little thought then that my husband would be a professor at the seminary and that I would spend so many years on the campus. I think General Trimble made his escape later through the assistance of some southern women who came to Gettysburg after the battle purposely to help Confederate officers to get away'

+General Trimble was removed to Fort Wayne, and detained there until February 1865. He had been in railroad service for years and his acquaintance with northern as well as southern railroad systems made him," a dangerous man" in the eyes of Union leaders.-{E.S.}

Four such ladies from Baltimore were at our house for a few days. They were brought to us and introduced by Dr. John A. Swope who was then living in the town. One was Mrs. Banks and the name of the other was Mrs. Warrington. I do not remember the name of the other two, a lady and her daughter, and am not sure that we ever knew. They were very delightful ladies and were supplied with money. They spent the whole day out on the field and in hospitals where the Confederate wounded were. We did not suspect their intestions at first, but when they tried to buy up men's civilian clothes, and even women's clothing, we began to understand what they were about. As soon as my father learned what their real mission was, he insisted that mother must send them away. He would not tolerate any Confederate sympathizers in our house. He had seen too much of what our brave men had suffered because of the war, especially in the Battle of Gettysburg.

The ladies begged very earnestly to be allowed to stay, saying that they were much pleased with their accommodations. They especially liked mother's tea and hot biscuits, and in fact everything she put on the table. Mother was sorry to send them away as they were willing to pay well for every attention. They even offered to increase the amount, but father was relentless. He was not willing to sacrifice his principals, even though the losses he had suffered during the war made ready money very desirable. The four ladies left our home very reluctantly and we could not help wondering whether they found another place they liked.

Sunday, the second day after the battle, and the fifth day of July was a day long to be remembered. It was so different from any other Sunday we had ever known. It had rained very hard Saturday night and the atmosphere was stifling and extremely impure from the many unburied horses and human being scattered over the vast field. The cavalry field alone covered sixteen square miles and the entire battlefield, forty. On this Sunday morning after the weather had cleared, father, a little rested from the strenuous work of the day before-that terrible Saturday of which I have already written-felt that he must continue to care for the poor wounded and dying men who had fought so bravely. He hitched the horse to the spring wagon, put in plenty of straw to make it as comfortable as possible, and drive out over the battlefield. he brought many loads of wounded to the emergency hospitals in the churches, the college and seminary. In these buildings and later tents put up by the government in the woods east of town,the women and girls of Gettysburg ministered to the sick and wounded. Many of the temporary nurses laid aside their full hoop-skirts and donned hospital garb so that they might perform their tasks more efficiently.

The young people from the different choirs delighted to sing at the hospitals. Many romances developed. One of our most intimate friends married a southerner whom her mother had nursed back to health.

The Sister of Charity from Emmitsburg made their appearance very soon after the battle. I recall many instances of their kindness and usefulness as I watched them sit by the hospital cots, moistening the parched lips, fanning the heated brow, writing a letter to the loved home-folks or reading and praying with the wounded and dying. No wonder the men learned to admire and love them!

Soon the town began to fill with friends and strangers, some intent on satisfying their curiosity and others, shame to say, to pick up articles of value. Blankets, sabers, guns and many other things were thus obtained and smuggled away or secreted, Some time after the battle when the government began to count up the losses, houses in Gettysburg were searched and some yielded sound and well preserved government supply.

Among the visitors who came to Gettysburg were friends and acquaintances of our family, many of whom we were glad to welcome. But we could not help being amused, saddened as we were, by some who claimed acquaintance in order to have a stopping-place. As I was the only member of the family who was not suffering from biliousness and illness, I was deputed to receive most of the visitors.

Being occupied in this way and in caring for the other members of the family, I did not get out on the battlefield for some time, but when I did find time to go, there was still much to horrify. many trenches in which soldiers were buried were necessarily very shallow and gruesome sights greeted those who came near. It was not unusual to see a hand or foot or other part of the body protruding from the ground. When my sister Annie was walking over the field, several weeks after the battle, she picked up a hand, dried to parchment so that it looked as though covered with a kid glove. There was nothing repulsive about the relic, and we all remarked about the smallness of the fingers. We guessed that it must have belonged to a very young soldier or a southerner who had never worked with his hands. To conceal skeletons from view, I would collect army coats lying about the place them over the bones.

Many of our neighbors who had left their homes at the first alarm did not return until everything was quiet. Of course they found their once orderly houses in confusion; beds had been occupied, bureaus ransacked and contents scattered over the house. The larders had been searched for eatables and nothing remained that the soldiers could find use for. We felt indignant, after our terrible experiences to have some of our neighbors blame us because we did not watch over their homes and protect their property which we had been powerless to prevent, They did not seem to realize that to save lives was the sole concern of those frightful days-property and material things faded into the background. We were ready to use ourselves and all we had in service for the men who saved our town and people. How we studied to save them in every possible way! WE cooked and baked and invited them into our homes and to our tables loaded with all the food we could collect and prepare. Most of our citizens were occupied as we were, helping whenever opportunity offered. True, we had a few people in our town who were dubbed "copperheads" because they did not ring true blue.

Father acquired a reputation among the soldiers by his ability to cure felons. many of the men were afflicted in this way and suffered keenly, so that they could not sleep. He would hold the afflicted finger or thumb tightly in his closed hand until the throbbing ceased and the fever left. This was very painful to the sufferers and often tears would pour down their cheeks during the curing process. Father also suffered, feeling the pain sharply in his own hand and arm. But he never failed to effect a cure. The men were so grateful, and they would beg him to let them pay him for the cure, but he would never accept any remuneration from them.

Many years after the Battle of Gettysburg, when we had moved to Kansas, we were sometimes reminded of the events of those by-gone days. Mr. Hursh, the father of one of the students at Midland College, of which my husband was president, invited us to visit his home in Lancaster, Kansas, he had been in Gettysburg after the battle serving in the Quartermaster's Department. He told us of various people he had met and mentioned among others a "fine gray-haired gentleman who had a grain and lumber yard." He said he never saw anyone so devoted to Bible reading. Much pleased, I told him who the man was-my father.

The time I have spent in recalling to mind and writing out these memories of the Battle of Gettysburg has been of mingled pleasure and pain. Living over the days when our family was an unbroken circle has brought back the joy of childhood and youth; but I cannot help feeling again some of the mental and physical strain under which we passed our days and nights. This very tenseness served to fix impressions in my young mind so indelibly that now when I have grown old, I find them clear and undimmed.

Death Claims Aged Resident After Illness Of Four Hours Duration

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mrs. Liberty Augustus Clutz, widow of Dr. Jacob A. Clutz, formerly a professor of the Lutheran Theological seminary here, died at 12:30 o'clock this afternoon at the home of her son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. Mark K. Eckert, Springs avenue. She was 82 years of age.

Mrs. Clutz arouse this morning in usual health, and was taken ill about 9 o'clock, failing rapidly until the end this afternoon. Death was caused by cerebral hemorrhage.

NATIVE OF COUNTY

A daughter of the late Jacob S. and Sara (Diehl) Hollinger, Mrs. Clutz was born in Heidlersburg, but spent the greater part of life in Gettysburg.

She was living in Gettysburg in a house on the site of the Lincoln school building, York street, during the battles here in 1863, and two years ago, she had published her personal recollections of those stirring times.

She was married to Doctor Clutz in 1872. He died at Stockholm, Sweden, September 7, 1925, while attending a Lutheran convention, after being run down by an automobile truck.

ACTIVE CHURCH WORKER

Mrs. Clutz was a life-long member of Christ Lutheran Church, and always took an active part in work there.

Surviving are two daughters, Mrs. Eckert, with whom she resided since the death of her husband; Mrs. Julia T. Peters, New Cumberland; three sons, Dr. Frank H. Clutz, Broadway; Ralph R. Clutz Bendena, Kansas; and one brother, J.A. Hollinger, Hagerstown; one sister, Mrs. Annie H. Nelson, Chambersburg, and by ten grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements will be announced later.

The Gettysburg Times

{Gettysburg, Pennsylvania}

December 1 1928

MRS. CLUTZ IS BURIED TODAY

Funeral services for Mrs. Liberty Augustus Clutz, widow of Dr. Jacob A. Clutz, who died last Saturday afternoon, were held this afternoon at the home of her son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. Mark K. Eckert, Springs avennue. The services were in charge of the pastor Rev. Dr. Luther Kulhman, acting pastor of Christ Lutheran church, assisted by the Rev. Dr. A.R. Wentz, of the seminary. The sermon was preached by the Rev. Dr. A.E. Wagner, Hallam, former pastor at Christ Lutheran. Internment was private in Evergreen cemetery.

Pallbearers were, Dr. Albert Billheimer, J.L. Burgoon, Harry Snyder, Dr. J. E. Musselman, Dr. Raymond Stamm and James Cairns.

The Gettysburg Times

{Gettysburg, Pennsylvania}

December 5 1928

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

www3.gettysburg.edu/~jrudy/History/The Battle of...

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG (pg. 166-178)

By Mrs. Jacob A. Clutz

(Liberty Augustus Hollinger)

Edited by Elsie Singmaster, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

LIBERTY AUGUSTUS HOLLINGER was sixteen years old at the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, the eldest of a family of four girls and one boy, living with their parents at the eastern end of the pleasant, tree-shaded town. Besides the Lutheran Theological Seminary and Pennsylvania (now Gettysburg) College, the town contained an academy for boys and two private schools for girls. Its chief industry was the manufacture of carriages in which about two hundred men were engaged.

Mrs. Clutz speaks with naive admiration of the beauty of her young sister. She herself retained until her death at the age of eighty-one the characteristic charm of her family. She was married to graduate of the seminary, Jacob A. Clutz, who, after serving various parishes and being president of Midland College at Atchinson, Kansas, returned to Gettysburg as pastor of St. James Lutheran Church. He was afterwards a professor at the Lutheran Theological Seminary. In Gettysburg, her large family married and gone, Mrs. Glutz was happy in her garden, her friends and her books. She never ceased to believe the Civil War was a sad necessity; she always revered Abraham Lincoln.

In attendance at a religious convocation in Sweden, Dr. Clutz was struck by a car are fatally injured. With the same fortitude with which she had ministered to the wounded in her girlhood, Mrs. Clutz endured this overwhelming shock during the few years of life which remained.

Her reminiscences were written in 1925, sixty-two years after the battle. They are remarkable only as any simple, vivid narrative is remarkable. They are especially interesting because they show calmness and efficiency with which the citizens of Gettysburg, even children, met the most terrible of disasters.

{Elsie Singmaster}

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

My Children, and other members of our family, have often expressed a wish that I would make some permanent record of any recollections of the Battle of Gettyburg. So many years have passed that many things have entirely escaped my memory. But this year, 1925, the anniversary of the battle has happened to fall again on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. In imagination I live it all over almost as though it were just occurring. So many vivid pictures crowd my mind and fill my soul, that I hesitate to try to describe them as they occurred. But I will do the best I can.

At the time of the battle I was a young girl of sixteen. We were living on York street where the present high school building stands. Our house, a roomy brick one, stood in the center of a large plot of ground between the York Pike, which was the continuation of York Street, and what was known as the Bonneauvville, or Hanover Road, now Hanover Street. there were two roads, and a few opposite on the other side.

There was excitement in Gettysburg for some days before the battle, especially during the preceeding week when a detachment of Confederate cavalry entered the town and passed on down the Baltimore Pike. There was great commotion on the morning of Wednesday, July 1st, when the report spread from door to door that the enemy was coming in force. We could also hear an occasional boom of cannon west of town. My father was at the warehouse down along the railroad, on the corner of Stratton Street, where he was engaged in the grain and produce business. My brother Gussie, then a little lad of about 5 years, was eager to go to see father because he wanted to show him his first waist and breeches. I decided to go with him to please him, and also to hear what father thought about the situation. He did not seem in the least excited, and advised a little calm waiting for further developments. When I got home and turned into our gate I knew that the excitement was increasing. Many of our neighbors left their homes only to encounter greater danger elsewhere. Meanwhile, their houses were ransacked by the Confederates who took possession of most of the houses they found deserted and helped themselves to whatever they wanted, especially food.

While we were deliberating what would be best to do, two wounded Union officers came up, and a captain with a bullet in his neck, and the other a lieutenant with a bullet in his wrist. Both were suffering greatly. We appealed to them for advice, and they immediately asked about the cellar. The heartily agreed that it would be a safe place during the battle. We found mother lying in a faint from the excitment, and the officers first carried a rocking chair to the cellar, then mother herself. They then said that they must hurry off or they would be taken prisoners by "Johnny Reb."

In a little while General Howard's troops of the Eleventh Corps retreated through the town to Cemetery Hill past our house. They were closely followed by the Confederate troops and as e saw the gray uniforms, we thought with fear of the two kind officers who had delayed their departure in order to give us help and advice. We were very happy to hear from them after the battle that they had reached the Union lines safely, and later that they had recovered from their wounds. As the two lines of soldiers ran past, firing as they went, we watched them through the cellar windows. Oh! What horror filled our breasts as we gazed upon their bayonets glistening in the sun, and heard the deafening roar of musketry! Mother was roused to consciousness by the terrific explosions and murmured over and over, "have they shot at the town?"

Soon we heard that General Reynolds had fallen in the grove west o the seminary, now known as "Reynolds Woods." We felt then that we were indeed in the midst of a serious stife. General Howard's men had sought the hills south of the town, both for greater safety and to prepare for further battle in a stronger position. The Confederates filled the town. They were appearing everywhere on the streets and taking possession of our neighbor's houses that had been abandoned. After making biscuits in a house across the street several called to Julia, my sister, who was on our balcony, and asked for butter for their biscuits. She saucily answered, "If you are hungry you can eat them as they are." They laughed and went back into the house.

Some of them rode into our yard and demanded the keys to the warehouse from father, who had locked it and come home when our men retreated. He refused to give them up, and they said calmly that of course they would get in. "Well," said father, "if you do I cannot prevent it, but I am not inviting you by giving you my keys." They then requested father to allow them to come into the house, and asked whether we would not cook and bake for them. Father again said "No," and when they insisted Julia came to the rescue. When she stepped out of the cellar and said that is would be impossible for us to do so, it was as though a vision had appeared. Without another word they quickly rode out of the yard. She was at that time between fourteen and fifteen years old, a very attractive child, with dark brown eyes and beautiful brown curls, who always seemed to attract and impress strangers.

The same men came a number of times and wanted to take our horse and cow. Father always told them that the horse was too old to be of any use to them, and for the time being they left the horse and the cow. There was a flourishing patch of corn back of the house near the barn. This was a temptation for their horses, but father simply told them that they could not use it, and wonderful to tell they never did. I do not why they maintained such a gentlemanly demeanor unless it was father's silvery head that awakened their respect. He was not yet forty-three years old, but his hair and beard had turned gray early and were as white as snow, making him look quite venerable. Of course the Confederates, forced the locks of the warehouse and took what they wanted and then ruined everything else. They opened the spigots of the molasses barrels and allowed the molasses to run over the floor. They scattered the salt and sugar on the floor also, and everything else that was accessible.

Finally the also took our horse when they retreated on Saturday, but I suppose they soon discovered that father had told them the truth when he said it was too old for service. At any rate they did not take it very far, and a few days later we heard that it was at Hanover. Father went and proved his property and brought it home no worse for the capture and little trip. The animal had been used many years as a draft horse at the warehouse, and was well known all over the town and through the surrounding country.

We stayed in our cellar most of the time during thee three days of battle. How glad we were for such a safe retreat from all harm and danger! A few bullets struck the cellar doors, and occasionally we could hear them strike the brick walls of the house, but we felt perfectly safe. There was a large wheat-field south of our house on the Culp farm, ripe and ready for harvest, and it seemed to be full of Union sharpshooters. We could see them pop up and fire when any of the Confederates, especially officers rode by. We could see them in the trees and beyond also. When father left the cellar to feed the chickens or to milk the cow, the bullets

flew about him. Finally , he spoke to the sharpshooters about it. An officer said, "Why man, take off that gray suit; they think you are "Johnny Reb". He put on a black suit and had no further trouble. We ate cold dinners in the cellar, and sometimes breakfast too. One morning the cannon planted around our house began to shake the house with their unearthly explosions before we were ready to descend. In the evenings, after the firing ceased, we ventured up into the kitchen to cook a hot meal, and we slept upstairs every night.

Such was our life for three days, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. On Saturday morning we went downstairs to try to get a little breakfast and soon realized that all was quiet there. We ventured out to look around. The few Confederates seemed to be either wounded or were stragglers. The battle was ended and it was not long before our own Union soldiers began to appear. A number of them came to the house, so tired and hungry that mother invited them in, and began to cut bread for them. She spread he bread with butter and then set out a crock of apple-butter, telling them to help themselves. They did so in a hurry and declared that is was "the best stuff they ever ate." Later in the day father found a number of worn and bedraggled Union soldiers in the barn. We fed them also, and they became very friendly. Among them was a German who fell in love with Julia. He would say to her, "Now, Yulie, you say Chorge, no more drink, and Chorge no more drink. He would also repeat the saying that was common among the Germans of the Eleventh Corps. "I fight mit Sigel, nut I runs mit Howard." There were two young soldiers among these who came to visit us a number of times after the war was over. One was a Dr. Agnew, and the other a Mfr. Wallace.

There was a great deal of rain after the battle. Some thought that is was because of the heavy cannonading and the explosion of so much ammunition. How we suffered from the awful, awful stench coming from the dead horses and even the dead and wounded soldiers from both armies who were still unburied or uncared for! Father felt that he must help out on the field. Hearsick and soul-sick and with aching back he served the terribly wounded with the one thing they clamored for-water, water, until he was ready to drop from exhaustion.

One of the most interesting incidents in our experiences was the appearance of General Lee and his staff in front of our house on the evening of the first day of the battle. I very well remember his face and striking appearance as he sat on his splendid was-horse, "Traveller." they were in front of our house for sometime, while General Lee was observing, through his field glasses the hills south of the town on which General Howard had taken refuge, and where now the whole Army if the Potomac was taking its stand to give further battle to the Army of Northern Virginia. After a long and careful examination he took his glasses down and I heard him say to the officers near him something like this: "Those hills all around are natural fortresses. Wonderful! Wonderful! It will be very difficult to capture them or dislodge the troops holding them."

There was a handsome young officer on GeneraL lee's staff who backed his horse up quite close to the gate where Julia and I were standing. He presented a very striking figure, mounted on a beautiful sorrel with a red sash passed over his right shoulder and fastened at his waist in a knot from which the fringe fell over his knee. I think his name was Breckenridge. He seemed to give no heed to what his commander was saying about the wonderful hills on which our men were entrenched. I heard much of what they were saying.

I also heard much that was being discussed right by me. Julia was telling the young officer how our troops were coming to Gettysburg from all points, and that soon there would be a formidable army gathered which they could not withstand. He looked at her quizzically and seemed amused, but he made no unkind or harsh reply. How much he believed we could not tell. Father kept telling the Confederates on every opportunity that they would soon be wiped out, as our men were coming in great numbers from all directions. What seemed to dishearten them more than anything else was that there seemed to be so large a number of able-bodied men left on the farms and in the towns for service in any emergency. All their men, young and old, were in the ranks, with no reserves left. They realized that the North could continue the war indefinitely,while they had about exhausted their resources.

The second day of the battle many wounded were carried through our yard on stretchers. Sometimes blood dripping through the stretchers, and their faces were pale as death. Once in a while a man was entirely covered, too badly wounded to be seen. Some were able to help themselves and came limping through with the blood oozing from their wounds. One very youthful soldier in a blue uniform hobbled into the yard with a wound in his foot. The blood soaking his shoe, and mother urged him to go to a hospital and have his shoe removed and the wound dressed as soon as possible, as his foot would swell so that the show could not be removed. We could not tell whether those on the stretchers were Confederate or Union soldiers, but I suppose that most of them were Confederates, as they would likely care for their own wounded first.

On the evening of Thursday, the second day, a number of Confederates came into the yard and asked father to get them supper. He said he did not think that we could feed them. Just then Julia came out of the cellar and stood on the ssteps which led up into the yard outside the house. The minute they saw her their attitude entirely changed. They became very courteous and politely asked us girls to sing for them. Julia was very patriotic and told them we would not sing to please Confederates, but that possibly our boys in blue might hear us and be cheered. So we sang a number of our own Union war songs with which we were familiar. Each time the Confederates would respond with one of their songs. Presently an officer rode into the yard and said to one of the men, "Cap, you'd better be careful about these songs." The captain answered, "Why thats all right. They sing their battle songs, and hen we sing ours." They asked us whether we had an instrument, and they wanted to come into the house and have a pleasant social time. But father and mother would not consent.

On Saturday afternoon a Confederate surgeon came into the yard and lifting his hat very politely, asked mother if he might sit on the porch and rest. He was very tall and fine-looking, a perfect gentleman both in appearance and manners. He appeared tired and worn. My sister Annie, who was then about nine years old, was standing near him and he took her hand and asked mother if he might hold her on his knee. Mother and I were busy getting supper, and when i was ready she invited him to eat with us. He declined, very polietly, saying that he could not possibly eat anything as he was too weary and heartsick from amputating limbs all day. We could see blood-stains on his boots. There was an emergency hospital in a carpenter's shop not far from our house. The carpenter's bench was used as a operating table, and my sister Bertie, who had gone there several times said that there was a big pile of legs and arms outside the window. She was about seven at this time. No doubt it was in this shop that he had been operating. We did not learn his name.

When hospitals were better established we carried dainties to the wounded and dying of both armies, nearly every day. Mother, especially, was tireless in her willingness to bake and work and to carry cheer and comfort to the suffering soldiers. Of course other women were similarly engaged, both women of Gettysburg and many visitors who cam to minister to the wounded. One of the familiar figures on the streets in those days that interested us very much was Dr. Mary Walker. Her low silk hat, with bloomers, and a man's coat and collar, seemed invariably to call forth a laugh or a yell from the young boys, and many a smile and shrug from the older people.

In one of my mother's visits to the hospitals she found a very young Confederate soldier, a mere boy, who was fatally wounded. He seemed so happy to see her, and begged her to come again. He said he loved to look at her because she reminded him of his mother. But, alas! The next time she went to see him she found his cot empty. Mother also visited a young Union soldier by the name of Ira Sparry who lay badly wounded in the Reformed Church. She was much pleased with his general appearance and manners. He seemed to be getting along all right, and when he learned that his wife was coming to see him he was happy. Their home was in Portland, Maine. She finally arrived and came to our house, but too late to see her husband. He had suddenly taken a turn for the worse, and had died and was buried the day before she reached Gettysburg.

This woman came to Gettysburg with the father of a wounded boy who was at our house. The boy's first name was Paul; I do not remember his other name. His right arm had been amputated at the shoulder, and it was my duty to dress the wound every morning and evening. How still he used to hold while I thoroughly cleaned it! His father took him home, and we heard later that though the wound had healed he died from the effects of it. While he was at our house he was so painfully nervous from the pain and shock that he had to have an anodyne every evening on retiring so as to get some sleep and rest.

Still another interesting case was that of a young soldier whom we used to visit in the general hospital which was established in a grove along the York Pike, now the Lincoln Highway. The boy's left foot had been amputated, but he was always very jolly. Three or four years ago he came back to see the battlefield for the first time and he came out to our house at the seminary with Mr. Taughinbaugh, at whose house he was lodging. He asked whether my name had been Liberty Hollinger, and he recalled my visits to the hospital. At first I could not remember him, but after a little conversation it all came back to me again very clearly.

On the afternoon of the first day's fight, when our men were falling back, a very young Union soldier came into our yard, and asked mother to keep his blanket and knapsack for him. He said he was not well and that they were too heavy for him to carry. He told her that if he never got back for them she should keep them. We never heard from him again.

One day Julia and I went out to the seminary's building to see a wounded Confederate officer, Major General Trimble. I do not know how we came to do this, but I remember that we gave him a bouquet of flowers, and that he and his orderly were very polite and kind to us. I little thought then that my husband would be a professor at the seminary and that I would spend so many years on the campus. I think General Trimble made his escape later through the assistance of some southern women who came to Gettysburg after the battle purposely to help Confederate officers to get away'

+General Trimble was removed to Fort Wayne, and detained there until February 1865. He had been in railroad service for years and his acquaintance with northern as well as southern railroad systems made him," a dangerous man" in the eyes of Union leaders.-{E.S.}

Four such ladies from Baltimore were at our house for a few days. They were brought to us and introduced by Dr. John A. Swope who was then living in the town. One was Mrs. Banks and the name of the other was Mrs. Warrington. I do not remember the name of the other two, a lady and her daughter, and am not sure that we ever knew. They were very delightful ladies and were supplied with money. They spent the whole day out on the field and in hospitals where the Confederate wounded were. We did not suspect their intestions at first, but when they tried to buy up men's civilian clothes, and even women's clothing, we began to understand what they were about. As soon as my father learned what their real mission was, he insisted that mother must send them away. He would not tolerate any Confederate sympathizers in our house. He had seen too much of what our brave men had suffered because of the war, especially in the Battle of Gettysburg.

The ladies begged very earnestly to be allowed to stay, saying that they were much pleased with their accommodations. They especially liked mother's tea and hot biscuits, and in fact everything she put on the table. Mother was sorry to send them away as they were willing to pay well for every attention. They even offered to increase the amount, but father was relentless. He was not willing to sacrifice his principals, even though the losses he had suffered during the war made ready money very desirable. The four ladies left our home very reluctantly and we could not help wondering whether they found another place they liked.

Sunday, the second day after the battle, and the fifth day of July was a day long to be remembered. It was so different from any other Sunday we had ever known. It had rained very hard Saturday night and the atmosphere was stifling and extremely impure from the many unburied horses and human being scattered over the vast field. The cavalry field alone covered sixteen square miles and the entire battlefield, forty. On this Sunday morning after the weather had cleared, father, a little rested from the strenuous work of the day before-that terrible Saturday of which I have already written-felt that he must continue to care for the poor wounded and dying men who had fought so bravely. He hitched the horse to the spring wagon, put in plenty of straw to make it as comfortable as possible, and drive out over the battlefield. he brought many loads of wounded to the emergency hospitals in the churches, the college and seminary. In these buildings and later tents put up by the government in the woods east of town,the women and girls of Gettysburg ministered to the sick and wounded. Many of the temporary nurses laid aside their full hoop-skirts and donned hospital garb so that they might perform their tasks more efficiently.

The young people from the different choirs delighted to sing at the hospitals. Many romances developed. One of our most intimate friends married a southerner whom her mother had nursed back to health.

The Sister of Charity from Emmitsburg made their appearance very soon after the battle. I recall many instances of their kindness and usefulness as I watched them sit by the hospital cots, moistening the parched lips, fanning the heated brow, writing a letter to the loved home-folks or reading and praying with the wounded and dying. No wonder the men learned to admire and love them!

Soon the town began to fill with friends and strangers, some intent on satisfying their curiosity and others, shame to say, to pick up articles of value. Blankets, sabers, guns and many other things were thus obtained and smuggled away or secreted, Some time after the battle when the government began to count up the losses, houses in Gettysburg were searched and some yielded sound and well preserved government supply.

Among the visitors who came to Gettysburg were friends and acquaintances of our family, many of whom we were glad to welcome. But we could not help being amused, saddened as we were, by some who claimed acquaintance in order to have a stopping-place. As I was the only member of the family who was not suffering from biliousness and illness, I was deputed to receive most of the visitors.

Being occupied in this way and in caring for the other members of the family, I did not get out on the battlefield for some time, but when I did find time to go, there was still much to horrify. many trenches in which soldiers were buried were necessarily very shallow and gruesome sights greeted those who came near. It was not unusual to see a hand or foot or other part of the body protruding from the ground. When my sister Annie was walking over the field, several weeks after the battle, she picked up a hand, dried to parchment so that it looked as though covered with a kid glove. There was nothing repulsive about the relic, and we all remarked about the smallness of the fingers. We guessed that it must have belonged to a very young soldier or a southerner who had never worked with his hands. To conceal skeletons from view, I would collect army coats lying about the place them over the bones.

Many of our neighbors who had left their homes at the first alarm did not return until everything was quiet. Of course they found their once orderly houses in confusion; beds had been occupied, bureaus ransacked and contents scattered over the house. The larders had been searched for eatables and nothing remained that the soldiers could find use for. We felt indignant, after our terrible experiences to have some of our neighbors blame us because we did not watch over their homes and protect their property which we had been powerless to prevent, They did not seem to realize that to save lives was the sole concern of those frightful days-property and material things faded into the background. We were ready to use ourselves and all we had in service for the men who saved our town and people. How we studied to save them in every possible way! WE cooked and baked and invited them into our homes and to our tables loaded with all the food we could collect and prepare. Most of our citizens were occupied as we were, helping whenever opportunity offered. True, we had a few people in our town who were dubbed "copperheads" because they did not ring true blue.

Father acquired a reputation among the soldiers by his ability to cure felons. many of the men were afflicted in this way and suffered keenly, so that they could not sleep. He would hold the afflicted finger or thumb tightly in his closed hand until the throbbing ceased and the fever left. This was very painful to the sufferers and often tears would pour down their cheeks during the curing process. Father also suffered, feeling the pain sharply in his own hand and arm. But he never failed to effect a cure. The men were so grateful, and they would beg him to let them pay him for the cure, but he would never accept any remuneration from them.

Many years after the Battle of Gettysburg, when we had moved to Kansas, we were sometimes reminded of the events of those by-gone days. Mr. Hursh, the father of one of the students at Midland College, of which my husband was president, invited us to visit his home in Lancaster, Kansas, he had been in Gettysburg after the battle serving in the Quartermaster's Department. He told us of various people he had met and mentioned among others a "fine gray-haired gentleman who had a grain and lumber yard." He said he never saw anyone so devoted to Bible reading. Much pleased, I told him who the man was-my father.

The time I have spent in recalling to mind and writing out these memories of the Battle of Gettysburg has been of mingled pleasure and pain. Living over the days when our family was an unbroken circle has brought back the joy of childhood and youth; but I cannot help feeling again some of the mental and physical strain under which we passed our days and nights. This very tenseness served to fix impressions in my young mind so indelibly that now when I have grown old, I find them clear and undimmed.