Early life and education

Maude E. Callen was born in Quincy, Florida, in 1898, one of thirteen sisters and orphaned by age six. She was raised in the home of her uncle, Dr. William J. Gunn, a physican, in Tallahassee, Florida.

She graduated from Florida A & M University in 19221 and then completed a nursing course at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.1,3 Later, while working as a nurse-midwife in Berkeley County, she received additional training from the Georgia Infirmary in Savannah, and in tuberculosis care at the Homer G. Phillips Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri.

Personal life

Callen married William D. Callen in 1921. He moved with her to Pineville when she was called as a missionary nurse.

Work as a nurse-midwife

In 1923, Callen moved to Pineville, Berkeley County, South Carolina, as an Episcopal missionary nurse.3 The position was intended to be temporary.1 She was one of only nine nurse-midwives in South Carolina at the time.

Callen operated a community clinic out of her home, which was miles from any hospital.1 It is estimated she delivered between six hundred and eight hundred babies in her years of practice.1 In addition to providing medical services, Callen taught women from the community to be midwives.

She provided in-home services to "an area of some 400 square miles veined with muddy roads", serving as "'doctor, dietician, psychologist, bail-goer and friend' to thousands of poor (most of them desperately poor) patients — only two percent of whom were white".

Conditions in Berkeley County were difficult:

"[A]t the edge of Hell Hole Swamp in Pineville houses were still lit by oil lamps, not electricity. Not having power lines meant no telephones, and people went to town by wagon or buggy."

"Nurse Maude recalled that there were only two cars in Berkeley County and none of the roads were paved. Many of her patients arrived at her home in oxcarts in the middle of the night."

"[After Callen purchased her own car to use for home visits, s]he frequently had to park her car and walk through mud, woods, and creeks to reach her patients."

In 1936, Nurse Maude joined the Berkeley County Health Department as a public health nurse. Her job included training midwives throughout the county. She taught young black women the proper practices in prenatal care, labor support, baby delivery, and handling of newborns.3 She also provided vaccinations and examinations to the children in nine schools and kept records on the children's eyes and teeth.

In December 1951, Life magazine published a twelve-page photographic essay of Callen's work, by the celebrated photojournalist, W. Eugene Smith. Smith spent weeks with Callen at her clinic and on her rounds in the community.3 Smith is quoted as saying the photographs he took of Nurse Maude were the "most rewarding of all [his] work" and that Callen was "the most completely fulfilled person I have ever known."

On publication of the photo-essay, readers donated more than $20,000 to support Callen's work in Pineville.2 As a result, the Maude E. Callen Clinic opened in 1953.3 Callen ran the clinic until her retirement from public health duties in 1971. The Maude E. Callen Clinic closed in 1986

[edit] Work with senior citizens

After her retirement in 1971, Callen petitioned county officials to start a Senior Citizens Nutrition Site, which operated starting in 1980 out of the clinic. As a volunteer, Callen managed the center, cooked and delivered meals five days a week4, and provided car service to seniors needing transportation.1 A local news article stated: "At 85, Miss Maude serves meals each weekday to some 50 elderly residents, most of them younger than she is."5 She is quoted as having said, on turning down an invitation from President Reagan to visit the White House, "You can't just call me up and ask me to be somewhere. I've got to do my job."

She continued her volunteer work until her death in 1990.

Early life and education

Maude E. Callen was born in Quincy, Florida, in 1898, one of thirteen sisters and orphaned by age six. She was raised in the home of her uncle, Dr. William J. Gunn, a physican, in Tallahassee, Florida.

She graduated from Florida A & M University in 19221 and then completed a nursing course at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.1,3 Later, while working as a nurse-midwife in Berkeley County, she received additional training from the Georgia Infirmary in Savannah, and in tuberculosis care at the Homer G. Phillips Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri.

Personal life

Callen married William D. Callen in 1921. He moved with her to Pineville when she was called as a missionary nurse.

Work as a nurse-midwife

In 1923, Callen moved to Pineville, Berkeley County, South Carolina, as an Episcopal missionary nurse.3 The position was intended to be temporary.1 She was one of only nine nurse-midwives in South Carolina at the time.

Callen operated a community clinic out of her home, which was miles from any hospital.1 It is estimated she delivered between six hundred and eight hundred babies in her years of practice.1 In addition to providing medical services, Callen taught women from the community to be midwives.

She provided in-home services to "an area of some 400 square miles veined with muddy roads", serving as "'doctor, dietician, psychologist, bail-goer and friend' to thousands of poor (most of them desperately poor) patients — only two percent of whom were white".

Conditions in Berkeley County were difficult:

"[A]t the edge of Hell Hole Swamp in Pineville houses were still lit by oil lamps, not electricity. Not having power lines meant no telephones, and people went to town by wagon or buggy."

"Nurse Maude recalled that there were only two cars in Berkeley County and none of the roads were paved. Many of her patients arrived at her home in oxcarts in the middle of the night."

"[After Callen purchased her own car to use for home visits, s]he frequently had to park her car and walk through mud, woods, and creeks to reach her patients."

In 1936, Nurse Maude joined the Berkeley County Health Department as a public health nurse. Her job included training midwives throughout the county. She taught young black women the proper practices in prenatal care, labor support, baby delivery, and handling of newborns.3 She also provided vaccinations and examinations to the children in nine schools and kept records on the children's eyes and teeth.

In December 1951, Life magazine published a twelve-page photographic essay of Callen's work, by the celebrated photojournalist, W. Eugene Smith. Smith spent weeks with Callen at her clinic and on her rounds in the community.3 Smith is quoted as saying the photographs he took of Nurse Maude were the "most rewarding of all [his] work" and that Callen was "the most completely fulfilled person I have ever known."

On publication of the photo-essay, readers donated more than $20,000 to support Callen's work in Pineville.2 As a result, the Maude E. Callen Clinic opened in 1953.3 Callen ran the clinic until her retirement from public health duties in 1971. The Maude E. Callen Clinic closed in 1986

[edit] Work with senior citizens

After her retirement in 1971, Callen petitioned county officials to start a Senior Citizens Nutrition Site, which operated starting in 1980 out of the clinic. As a volunteer, Callen managed the center, cooked and delivered meals five days a week4, and provided car service to seniors needing transportation.1 A local news article stated: "At 85, Miss Maude serves meals each weekday to some 50 elderly residents, most of them younger than she is."5 She is quoted as having said, on turning down an invitation from President Reagan to visit the White House, "You can't just call me up and ask me to be somewhere. I've got to do my job."

She continued her volunteer work until her death in 1990.

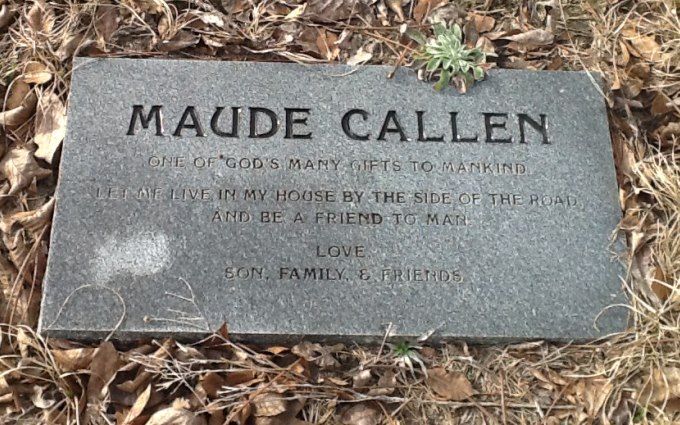

Inscription

Nurse Midwife

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement