Edited Text from Roger Jones Find a Grave ID 47311489;

Only U.S. Midshipman hung for mutiny in the Navy.

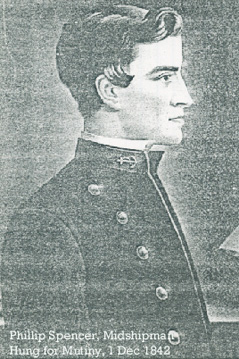

Philip first attended Hobart College, transferred to Union College but left after 6 months and through the influence of his father, John Canfield [Spencer], was placed as a midshipman on the brig-of-war, "Somers". Upon the return from a cruise, it was learned that Philip, then 19 years, and 2 seamen, had been hanged, 1 Dec 1842, for mutiny.

[From Microphoto M-330,"Abstracts of the Service Records of Naval Officers", Roll 6, No. 2166, National Archives, Washington, DC Philip Spencer--20 Nov 1841 Nov. 39 '41 to Resq (?) S at 5 St. Y.C. 462 Feby 7th'42 to the John Adams 566 21 Jul 1842 retd by the Potomac fr. Bowfish. Augt. 13th to the Somers 216 Died on board the Brig. Somers 1 Dec 1842.

Salute for Chi Psi Martyr Union College of Schenectady, NY, claims the title "mother of fraternities" because there, about a century ago, were organized six of the earliest Greek-letter societies. Last week one of them, Chi Psi, which calls its chapter alphas and its houses lodges, summoned 600 of its 300 members from all over the nation to Union for a celebration of its centennial. The name of Philip Spencer dominated proceeding. To Union's library the fraternity ceremonially presented a Chi Psi Alcove of 600 books on human relations and above it a portrait of Philip Spencer. At a banquet, John Wendell Anderson, Detroit lawyer and former Chi Psi president, gave the society $100,000 as the nucleus of a Spencer memorial trust fund to help the 25 active alphas payoff mortgages on lodges. This Philip Spencer was the son of John C. Spencer, President Tyler's Secretary of War. In 1841, when the prankish youth was fired from Hobart College of Geneva, NY, for neglecting his studies, he shifted to Union and promptly leagued with nine other students to create Chi Psi. Then, after six months, he quit Union, joined the Navy, and got a berth as acting midshipman aboard the brig Somers. One day in 1841, the Somers arrived in NY from Africa with shocking news: The 19-year-old Cabinet member's son and two other crewmen had been hanged at sea for mutiny. Comdr. Alexander MacKenzie insisted he had found on Spencer a list, in Greek letters, of potential accomplices and that the youth had confessed. In the furor that followed the writer James Fenimore Cooper charged that the Greek writing concerned Chi Psi and that Spencer had died guarding fraternity secrets. However, MacKenzie was court-martialed and acquitted. So, the Somers incident, recorded in naval history as a thwarted mutiny is revered by Chi Psi as a fraternal martyrdom.

[Ref: Newsweek, 12 May 1941, p.76. McKenzie, A. Slidell, No. 844, Commander, tried 28 Dec 1842; charges "Executions on board the US Brig Somers"; Sentence: "court of Inquiry" Statement of facts: with opinion that Commander McKenzie and officers honorably performed their duty to the service and their country". "Murder, --oppression--illegal punishment conduct unbecoming an officer--cruelty and oppression"; Sentence "Acquitted". Action of President or the Department "confirmed". A.P. Upshur. Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy)--Records of General Courts Martial and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department 1799-1867, M-273, Roll 1.]

The Court Martial convened aboard the USS North Carolina, New York, 1 Feb 1843, and continues through over 600 pages of the proceedings through the acquittal findings and decision of 28 Feb 1843. The excerpt from the logbook of the Somers states: "We left New York on the 12th of September 1842 civil time, arrived at Funchal Oct 5, 1842, arrived at Santa Cruz Oct. 8, 1842, arrived at Porto Praya Oct 21, 1842, arrived at Cape Meservado Nov 10, 1842, arrived at St. Thomas, Dec. 5, 1842; arrived at New York Dec 15, 1842." W. H. Morris, Esquire, of Baltimore had been appointed Judge Advocate by the Navy Department letter of 25 Jan 1843, signed by A. P. Upshur. The court was composed of officers. On 2 Feb 1843, Commander Alex R. Slidell Mackenzie pleaded, in writing, as follows: "I admit that Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, Boatswain mate Samuel Cromwell, and Seaman Elisha Small were put to death by my order as Commander of the U.S. Brig Somers, at the time and place mentioned in the charges, but as under the existing circumstances this act was demanded by duty and justified by necessity, I plead not guilty to all the charges." Morris read a statement of his conception of his responsibilities in this 'civil proceeding', requested a statement from defense as to its intended procedure so Morris could determine his course of action, saying, "This is thought by Government to be a case of great importance and it is not unlikely that an associate of masterly ability and whose capacity has been enabled by age to command the respect of the whole country may be sent to me as a coadjutor." On 3 Feb 1843, the statement of counsel for Defendant as to position of Judge Advocate was read into record. Morris then stated that except for rumor, he had no knowledge ofthe facts nor the government witness and was given an adjournment to Feb. 4. Morris read on Feb 4th, a letter from B.F. Butler and Chas. O'Connor "members of New York Bar, employed by relatives of Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, one of the persons for the murder of whom Mackenzie is on trial" requesting permission to be present and to participate in the proceedings. The request was denied by the Court. The Government presented several witnesses from the ship's officers and crew who established that Philip was placed in the Wardroom of the Sommers, handcuffed and in leg irons, the evening of 26 Nov 1842; that a day or two later Cromwell and Small were locked up with him; and that on the morning of 1 Dec 1842, all three were brought on deck and executed by hanging. The defendant then presented numerous witnesses of the ship's officers and crew for the purpose of establishing that the summary executions were justified, alleging guilt of Philip of mutiny and that time and circumstances did not permit bringing the three back to the United States for the court martial they had been led to believe they would receive. The "direct" evidence of mutiny consisted of the testimony of Purser's Steward Wales. Wales stated Philip approached him the evening of Nov 25, 1842, got him up on a boom where they would have privacy, placed Wales under another of secrecy, and then explained his plan to take over command of the Somers. Reportedly Philip was in league with about 20 of the Brig's company, who intended to murder all her officer, and commence pirating. Philip said he had plans drawn up on a paper in his neckerchief (felt by Wales); that Philip said some night when Philip had the midwatch, a "scuffle" would be started on the forecastle. Philip would cause participants to be brought to the Mast; that Mr. Rogers, Officer of Deck, would be called to "settle" the matter, where-upon Rogers would be seized and pitched overboard. Philip would then murder the Commander; then go to the War Room and kill officers there; return to deck and have two after guns slewed round to rake the deck; call the crew on deck; select mates for operation of ship; proceed to Cape St. Antonie of the Isle of Pines, where a conspirator would be taken on board, and then commence cruising for prizes. Philip reportedly had ideas, but not advanced plans, of taking over the ships he had been previously on. The other direct evidence was the "Greek Letter" paper found in Philip's razor case. Philip, when place in irons, told the Commander the plan was a joke. The Commander relied largely on the reported conduct of the crew to support his conclusions that summary execution was necessary. A mast or its gear feel on deck under a heavy sea the night after Philip's arrest and the noise and running of the crew on deck created the impression the mutiny was under way. Discipline on the ship had been good, until the departure from Cape Meservado. Philip had fraternized with the crew, rather than with fellow officers, giving them tobacco and candy against the Commander's orders; and Philip had displayed contempt fo the Commander. After Philip's arrest, the crew gathered in groups and talked among themselves, but dispersed when officers approached. When notified, just a few minutes before the execution and with nooses around their necks, Philip had asked the Commander if he was not acting hastily. Cromwell and Small had reportedly blamed Philip for their plight. Following the execution, the crew was asked to give three cheers for the flag, and discipline was returned. The commander reportedly had asked his officers what action they would take in his position. They gave him a written statement for immediate execution. At the court, they expressed the opinions that while not more than 14 of the crew members listed by Philip would have taken part in the proposed mutiny, that the mutiny against a crew of 120 would have been successful; that the ship did not have accommodations for additional prisoners, there for these three should be disposed of; and that the remaining officers could not have stood up under the burden of keeping watch on the ship and prisoners until the ship arrived at St. Thomas or a U.S. port. Ref: Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy)--Records of General Courts Martial and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department 1799-1867, M-273, Roll 49. In an old Chi Psi song, two of its many verses praise Spencer:

O here's to Philip Spencer Who when about to die

When sinking down beneath the waves Loud shouted out Chi Psi!

So, fill your glasses to the brim, And drink with manly pride

Humanity received a blow When Philip Spencer died.

Shortly after noon, on December 1, 1842, three hooded, manacled figures were hoisted to the main yardarm of the U.S. Brig-of-War Somers. The captain, as was his wont in such an emergency, delivered a pious homily to the remaining 117 men and boys, many of whom were weeping. The Stars and Stripes was raised. Then the crew gave three cheers for the American flag and were piped down to dinner, leaving the bodies of Boatswain's Mate Samuel Cromwell, Seaman Elisha Small, and Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer--the son of the Secretary of War--to swing in the rising wind. After dinner, under the personal direction of the captain, always as tickler for form, the three bodies were elaborately prepared for burial; at dusk they were ceremoniously lowered into the sea. Thus ended the only recorded mutiny in the United States Navy--if mutiny it was.

Fifteen days later the Somers dropped anchor in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, still carrying eleven prisoners. The story was soon common gossip in New York City, whereupon the Captain of the ship, Commander Alexander Slidell MacKenzie, U.S. N., was wildly acclaimed as a hero. Horace Greeley led the applause, "By the prompt and fearless decision of Captain MacKenzie", he wrote in his New York Tribune, "one of the most bold and daring conspiracies ever formed was frustrated and crushed". In his initial report on the trouble to Secretary of the Navy, Abel P. Upshur, MacKenzie described conditions aboard the Somers as approaching a state of imminent peril; a plot to seize control of the ship, head her into the Isle of Pines off the coast of Cuba and turn pirate had been foiled. Philip Spencer was the ringleader, Cromwell and Small his loyal cohorts. Those crew members who wanted to join forces with the mutineers were to have been retained; the rest, including all the officer, were to have been murdered. Only prompt and severe measures by MacKenzie had saved the ship. The plot had been uncovered on the night of November 25 by the purser's steward, James W. Wales, whom Spencer approached to join the conspiracy. Next morning Wales told the purser, who in turn reported to the brig's lieutenant, Guert Gansevoort. Gansevoort rushed to the Captain with the story. MacKenzie at first ridiculed the possibility of a mutiny, but on second thought he took a graver view. As a precaution, Spencer was put in irons on deck and forbidden to communicate with the crew. A list written in the Greek alphabet was found in Spencer's locker, which when translated named those crew members who were surely in the plot; those who might collaborate; and those who would have to be held against their will. Another piece of paper contained the specific assignments of the plotters at the moment of the mutiny. Small was mentioned twice on the lists, Cromwell not at all. Nonetheless, both men were confined on November 17. Tension mounted. The officers stood round the clock armed patrol. The crew went sullenly and anxiously about their business. During the night (of Tuesday the 29th) seditious words were heard throughout the vessel, MacKenzie wrote later. Various intelligence was obtained from time to time of conferences. ..Several times during the night, there were symptoms of an intention to strike some blow. (At no point, however, were these words or actions ever specified). Further doubts had assailed the Captain: What if other mutineers were at large? Four more of the crew were taken into custody the next morning. By Wednesday several officers had concluded that seven prisoners on deck would impede the operation of the ship----an opinion which forced decision on what to do with the original three. At this juncture MacKenzie formally asked his officers for their joint counsel, after taking "into deliberate and dispassionate consideration the present condition of the vessel. . ." The officers formed themselves into a court of inquiry which lasted into the following day. At length, prodded by MacKenzie, they announced that they had come "to a cool, decided and unanimous opinion that they (Spencer, Cromwell, and Small) have been guilty of a full and determined intention to commit a mutiny on board of this vessel of an atrocious nature and that the revelation of circumstances having made it necessary to confine others with them. . .we are convinced the safety of the public property, the lives of ourselves and of those committed to our charges require that. . .they should be put to death, in a manner best calculated. . .to make a beneficial impression upon the disaffected. No time was lost in reflection; the sentence was executed within two hours. MacKenzie certainly believed his command and his crew to be in danger. And had Philip Spencer not been the son of John Canfield Spencer, then President Tyler's Secretary of War, Mackenzie's story might have well gone unchallenged. But on December 21, a letter in the New York Tribune (later attributed to the elder Spencer) pointed out that by Mackenzie's own report, "the men were hanged when everything and person were perfectly quiet after four days of perfect security". No mutinous act had occurred in that interlude. This document set in motion a whole new line of inquiry. Many who had at first supported MacKenzie now reversed themselves and found the triple execution to be "a high-handed and unnecessary measure" When the preliminary naval court of inquiry failed to censure the Captain, such a halloo arose for a grand jury investigation that the Navy, anxious to protect its own, rather reluctantly arranged a court-martial for MacKenzie. He was acquitted, but the story that unfolded there could scarcely evoke the same verdict for history. As the omissions, embellishments, contradictions, and down right lies were sifted, the Somers tragedy emerged as the tale of mass hypnotic terror; of craven weakness on the part of Captain MacKenzie; and of apathetic, juvenile bravura on the part of a maladjusted eighteen-year-old, Philip Spencer. The discrepancies that so aroused MacKenzie's contemporaries are even more apparent to anyone who looks at the record today. MacKenzie and his officersjustified their action on the grounds of impending danger. Yetthe newly commissioned Somers was no warship: it had been turned into a training vessel for juvenile recruits. Only six of the crew were over nineteen years of age; forty-five were under sixteen; three were only thirteen. The few older hands were expected to teach seamanship to the apprentices. This floating academy had left New York in September, bound for the African coast, and had returned to Caribbean waters by the time the trouble occurred. It could not have been a pleasant voyage. The Somers was built to accommodate ninety; she carried one hundred and twenty. Floggings were frequent. The smaller boys lived in terror of Boatswain's Mate Cromwell, a large, burly, bad-tempered man. As for Captain MacKenzie, it would have been difficult to find a man less equipped to condition young boys to a naval career. Medium-sized, red-haired, mild-mannered, he was a thirty-nine prim, severe, fussy, sanctimonious, humorless, vain, moralistic, vacillating in times of crisis, and above all, vastly inhuman. Many who sailed with him on that voyage were to desert the sea forever. His real aspirations were literary rather than nautical. Born Alexander MacKenzie Slidell, he revered his middle and surnames at the behest of a wealthy uncle who wished to perpetuate the Mackenzie line--and thereby inherited enough money to allow him to pursue a literary career on the side. He wrote six books and quantities of tedious, if shorter, discourses; his pen was seldom still. It is worth nothing that MacKenzie's brother was John Slidell, the Confederate envoy to Britain who was snatched from the British steamer Trent by the Union Navy in 1861; his son, Ranold became one of the most daring and successful Indian fighters in the history of the west. Due largely to the backing of his friend Washington Irving, MacKenzie's book, A Year in Spain, was an immediate success in both America and England. At twenty-nine he was mildly famous. His style was florid, but so was the era. The Navy was sufficiently impressed by this unaccustomed talent in its ranks to accord MacKenzie unusual consideration--though he was also a diligent and scrupulous officer. He rose rapidly to independent command, as much on the strength of his literary as his naval accomplishments. And this literary propensity stood him in good stead after the mutiny; during his various trials he wrote four versions of the affair, each longer than the last, and each containing new and fanciful embellishments; like a cuttlefish in danger, he defended himself by emitting blasts of ink. Philip Spencer came to the Somers with a tarnished reputation. A slouching, sullen boy with a mop of dark hair and a cast in one eye, he had managed thus far in life to make a mess of everything he had attempted. After spending three years as a recalcitrant freshman at Geneva (now Hobart) College, he was thrust into Union college by his outraged, domineering, short-tempered father, a lean and hard man with eyes "fierce and quick rolling", and a face bearing "an unpleasant character of sternness". Here Spencer remained long enough to help found the Chi Psi fraternity, which still toasts him in its rituals. A further brush with the authorities landed him in the Navy, after a final warning from his father that disinheritance would follow should he fail once more. He was commissioned an acting midshipman in November 1841, joining a squadron off Brazil. He began to drink heavily and was shipped back to New York in disgrace in July 1842. Once again, he got another chance--his last. Through his father's intervention he was restored to his rank, boarding the Somers two weeks later. No one could have appealed less to the prissy, fastidious MacKenzie. Nor did Spencer get on with his fellow officers, most of whom were hand-picked proteges of the Captain. Now unnaturally, this lonely, defiant outcast of eighteen turned to the crew for companionship, and inwardly conjured up grandiose dreams of glory and revenge as a solace to this ego. Spencer alternately bought and clowned his way to popularity with the crew. He bribed Waltham, the Negro wardroom steward, to steal brandy for him and the bibulous Seaman Small and went into hock for then pounds of tobacco and over seven hundred cigars, largely for Cromwell (these despite MacKenzie's sharp disapproval of tobacco and his conviction that "the drinking of brandy is even more dreadful than malaria". Spencer could be seen at odd hours, joking with the men, cutting capers for the boys, throwing coins on the deck like an emperor and watching the rabble scramble for them. He had a trick of dislocating his jaw and by "contact of the bones" producing tunes "with accuracy and elegance", which threw his audience into raptures. Spencer's scarcely concealed contempt for MacKenzie behind his back (although he was careful to be civil face to face) further endeared him to the crew. Small and Cromwell, his chief cronies, were hardly desirable companions for an unstable boy. Small had lost most of his berths through drink, Cromwell at various times had been both a slaver and a pirate. It is not clear why these two seafaring hobos should have been chosen to train young, inexperienced recruits (MacKenzie, in a peculiarly macabre gesture, was to delay burial of the three mutineers for an hour to have Cromwell's head shaved. The scars of violence revealed thereon somehow assured the Captain of the wisdom of his course). No doubt in payment for liquor and cigars, these two men regaled Spencer with tales of a lurid past, real or fancied. Always addicted to blood and thunder thrillers, he evidently began to brood on the delicious possibilities of a life of piracy---with its rich treasure, daring forays, beautiful women--and himself, a well-beloved by awe-inspiring hear, in full command. Whether two such seasoned hands as Small and Cromwell ever took him seriously, or whether they simply played up to him for handouts, is not known. There is nothing on the record, in fact, to indicate that Cromwell had even heard of the plot. The purser's steward, James Wales, was the first to report that a mutiny was in the making. Yet later inquiry revealed that the plump, sly "Whales" was in bad odor with MacKenzie at the time because of some unspecified shady transaction in Puerto Rico. It took little intelligence to see that Philip Spencer was MacKenzie's bete noire, and any derogatory information about him might well boast the sagging stock of any informant. MacKenzie did in fact advance Wales to the rank of acting midshipman after Spencer's death and recommended that the rank be made permanent. No one knows how true Wales' report of a mutiny was, and no one made the slightest attempt to find out. From that moment on, the conduct of MacKenzie and his officers seems at best indefensible; despicable is a more accurate term. Instead of making sober inquiry into the facts, they succumbed to unconcealed hysteria. The first and obvious step was to examine Spencer. Yet Spencer was only twice questioned. Once casually on the twenty-sixth before his arrest, and again just an hour before his death, at which time the miserable boy admitted that plotting mutinies "had become a mania with him", a childish sort of game. The noose was strong punishment for this troubled adolescent. Spencer, having originally been told that he would be taken to New York for trial, bore himself well in confinement. But the sight of him and his fellow lying in fetters apparently did nothing to allay the mounting fears of the officers. A top gallant mast snapped. MacKenzie read dark meaning into this common accident. Seamen swarmed to repair the damage, and he later noted, "all those who were most conspicuously named in the program of Mr. Spencer. . .mustered at the main topmast head.' Withal, he reports no suspicious act, no hostile words. Only his fears led MacKenzie to arrest Cromwell. When the new prisoner was brought to where Spencer sat hunched in his double irons. It was Spencer who volunteered the information (as he was to do twice more before the end) that Cromwell was innocent. "I doubt if Cromwell could have been enlisted in any such enterprise, unless there was money aboard," he said a little bitterly. Guilt by association was the only charge leveled against Cromwell. He was condemned solely on Wales's surmise that he might have been involved because he was often seen in Spencer's company, and because Lieutenant Gansevoort later confided, "I don't like Cromwell's looks". And so it went for five terrible days. Each tiny incident of normal shipboard life was blown up to the bursting point. A midshipman herded a clean-up crew out of the twilight toward the officer's quarters ostensibly to man the mast rope in raising a new spar. The overwrought Gansevoort cried, "Halt, I say! I'll blow out the brains of the first man who steps on the quarter-deck". The midshipman had to rush to the front of his quivering group and explain himself. At any point those interested in mutiny might have rushed the officers and freed their comrades, yet no one made the slightest move to help the prisoners. The chances are that no one cared to; even Small was heard to mutter that Spencer was a little crazy. On the sixth day, the three men were hanged, although no single incident occurred that in any way further incriminated them. As MacKenzie explained later: "The deep sense I had of the solemn obligation I was under to protect and defend the vessel. . .the officers and the crew---the seas traversed by our peaceful merchantmen and the unarmed of all nations. . .from the horrors which the conspirators had mediated and, above all, to guard from violation the sanctity of the American flag"--the commander wrapped himself in the national ensign as habitually as he put on his nightshirt--"all impressed on me the absolute necessity of adopting some further measures for the security of the vessel." The proceeding was a shabby farce. MacKenzie later admitted that the kangaroo court of officers was assembled after he and Gansevoort had privately made up their minds to execute the prisoners. The court had no chairman, and the notes of its secretary were sketchy at best. The obvious people to examine--the three prisoners--were never called. But thirteen other witnesses did appear. One of them, later a prisoner himself, described the procedure: "Before a question of one officer was answered, other would be put by other officers, thus not only confounding the person being examined but themselves". A witness was told just to sign a statement--his answers would be filled in later. None of the information represented anything but hearsay and wild suppositions. A typical response: "I don't think the vessel is safe with these prisoners aboard. This is my deliberate opinion from what I heard King, the gunner's mate say: that is, that he had heard the boys say there were spies about". Afterward, Mackenzie saw to it that the faithful were rewarded. Seven of the witnesses were recommended for advancement. And it is worthy of note that during MacKenzie's own subsequent court-martial, when every effort was made to unearth supporting evidence for his actions, no single person was found who had ever heard the word "mutiny" mentioned aboard the Somers before Spencer's arrest. . .But they were hanged anyway, and on February 1, 1843, on a ship in New York Harbor Alexander Slidell MacKenzie was brought before a court-martial to defend himself. His own court-martial gave MacKenzie every leeway. He did not testify in his own behalf, thus saving himself from the hazard of cross-examination. Instead, he was allowed to present written explanations of the points raised by the timid, fusty little prosecutor. While MacKenzie sat resplendent in dress uniform day after day (he donned it on the slightest provocation), his loyal cohorts rehearsed the cooperative members of the crew until they had their stories letter-perfect. The less reliable were allowed to desert. The eleven prisoners were eventually freed without charge. New York grew bored and turned to more lively topics, a quiet acquittal became inevitable. The most searching questions were asked by a man who had no connection with the case. And the answers he offered make MacKenzie out part fool, part coward, part arrant knave. No less a personage than James Fenimore Cooper, himself an ex-midshipman in the Navy, carried the case to the public. Why he entered the controversy is not exactly certain. Disputatious by nature, and frequently involved in litigation, Cooper was a constant supporter of causes. Perhaps he simply hated the injustice of the affair or the sanctimonious behavior of MacKenzie. Or possibly, himself expelled from Yale, defiant of authority, and an ex-Navy man aware of the brutality of the fleet, Cooper identified himself with Spencer, whose life roughly paralleled his own early experience. MacKenzie had presented four prime reasons why the prisoners had perforce to forfeit their lives: First, the size and construction of the brig made it vulnerable. The prisoners had been held on deck because MacKenzie feared that they could not have been safely kept below. The partitions, he claimed, were so frail that they might have been forced. Cooper thought that an extremely far-fetched assumption. On the contrary, he suggested, the size of the Somers actually favored the officers. If there was real trouble, "twenty, or even ten armed men on the quarter-deck of a brig of 66 tons make them a very formidable array as opposed to any number of unarmed, or even armed men that could approach them at a time" Furthermore, her size was an asset from another point of view. "We see nothing to have prevented Captain Mackenzie from sending all but his officer below and of carrying the brig across the ocean, if needed, with the gentlemen of the quarter-deck alone." Under such circumstances, "even admitting a pretty widespread disaffection", the chances were nine out of ten in favor of her officers, "and that risk might have been run before an American citizen was hanged without trial". To MacKenzie's report that each night's darkness added to the peril on board the Somers; Cooper answered that there was no necessity for darkness, for every man-of-war had means of lighting her own decks. Second, MacKenzie cited "the sullenness, the violent and menacing demeanor and portentous looks of the crew". Cooper rejoined, "We entertain no doubt that much the great portion of the ominous conversation groupings, shaking of the head and strange look. . had their origin in the natural wonder of the crew at seeing an officer in this novel situation. . .The Somer had. . .at least 30 more than she should have had--and it is scarcely possible that with her boats bestowed and one third of her deck reserved for her officers, one hundred men could be on her remaining deck without being in "Knots". Third, though it had been suggested by some of the officers that the prisoners be landed at St. Thomas, in the Virgin Islands, MacKenzie had refused because he claimed it would have been virtual admission that the mutiny was beyond the control of the ship's authority. Cooper pointed out that since men-of-war often sought protection in a friendly port from starvation or disease, why not from mutineers? Fourth, MacKenzie said his officers were exhausted by the emergency watch and watch routines. Cooper ridiculed this assertion. What was there to cause all this exhaustion? Thousands were on watch and watch at night for long voyages".

Original Dana Spencer Text;

Only U.S. Midshipman hung for mutiny in the Navy

Philip first attended Hobart College, transferred to Union College but left after 6 months and through the influence of his father, John Canfield, was placed as a midshipman on the brig-of-war, "Somer". Upon the return from a cruise, it was learned that Philip, then 19 years, and 2 seamen, had been hanged, 1 Dec 1842, for mutiny. From Microphoto M-330,"Abstracts of the Service Records of Naval Officers", Roll 6,No. 2166, National Archives, Washington, DC Philip Spencer--20 Nov 1841 Nov. 39 '41 to Resq (?) S at 5 St. Y.C. 462 Feby 7th'42 to the John Adams 566 21 Jul 1842 retd by the Potomac fr. Bowfish. Augt. 13th to the Somer 216 Died on board the Brig.Somers 1 Decem 1842. Salute for Chi Psi Martyr Union College of Schenectady, NY, claims the title "mother of fraternities" because there, about a century ago, were organized six of the earliest Greek-letter societies. Last week one of them, Chi Psi, which calls its chapter alphas and its houses lodges,summoned 600 of its 300 members from all over the nation to Union for a celebration of its centennial. The name of Philip Spencer dominated proceeding. To Union's library the fraternity ceremonially presented a Chi Psi Alcove of 600 books on human relations and above it a portrait of Philip Spencer. At abanquet, John Wendell Anderson, Detroit lawyer and former Chi Psi president, gave the society $100,000 as the nucleus of a Spencer memorial trust fund to help the 25 active alphas payoff mortages on lodges. This Philip Spencer was the son of John C. Spencer, President Tyler's Secretary of War. In 1841, when the prankish youth was fired from Hobart College of Geneva, NY,for neglecting his studies, he shifted to Union and promptly leagued with nine other students to create Chi Psi. Then, after six months, he quit Union, joined the Navy, and got a bert as acting midshipman aboard the brig Somers. One day in 1841, the Somers arrivedin NY from Africa with shocking news: The 19-year-old Cabinet member's son and two other crewman had been hanged at sea for mutiny. Comdr. Alexander MacKenzie insisted he had found on Spencer a list, in Greek letters, of potential accomplices and that the youth had confessed. In the furor that followed the writer James Fenimore Cooper charged that the Greek writing concerned Chi Psi and that Spencer had died guarding fraternity secrets. However, MacKenzie was court-martialed and acquitted. So the Somers incident, recorded in naval history as a thwarted mutiny is revered by Chi Psi as a fraternal artyrdom. Ref: Newsweek, 12 May 1941, p.76. McKenzie, A. Slidell, No. 844, Commander, tried 28 Dec 1842; charges "Executions on board the US Brig Somers"; Sentence: "court of Inquiry" Statement of facts: with opinion that Commander McKenzie and officers honorably performed their duty to the service and their country". "Murder,--oppression--illegal punishment conduct unbecoming an officer--cruelty and oppression"; Sentence "Acquited". Action of President or the Department "confirmed". A.P. Upshur. Records of the Office ofthe Judge Advocate General (Navy)--Records of General Courts Martial and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department 1799-1867,M-273, Roll 1. The Court Martial convened aboard the USS North Carolina, New York, 1 Feb 1843, and continues through over 600 pages of the proceedings through the acquittal findings and decision of 28 Feb 1843. The excerpt from the log book of the Somers states: "We left New York on the 12th of September 1842 civil time, arrived at Funchal Oct 5 1842, arrived at Santa Cruz Oct. 8, 1842, arrived at Porto Praya Oct 21, 1842, arrived at Cape Meservado Nov 10, 1842, arrived at St. Thomas, Dec. 5, 1842; arrived at New York Dec 15, 1842." W. H. Morris, Esquire,of Baltimore had been appointed Judge Advocate by the Navy Department letter of 25 Jan 1843, signed by A. P. Upshur. The court was composed of officers. ON 2 Feb 1843, Commander Alex R. Slidell Mackenzie pleaded, in writing, as follows: "I admit that Acting Midshipman philip Spencer, Boats wainmate Samuel Cromwell, and Seaman Elisha Small were put to death by my order as Commander of the U.S. Brig Somers, at the time and place mentioned in the charges, but as under the existing circumstances this act was demanded by duty and justified by necessity, I plead not guilty to all the charges." Morris read a statement of his conception of his responsibilities in this 'civil proceeding', requested a statement from defense as to its intended procedure so Morris could determine his course of action, saying, "This is thought by Government to be a case of great importance and it is not unlikely that an associate of masterly ability and whose capacity has been enabled by age to command the respect of the whole country may be sent to me as a coadjutor." On 3 Feb 1843, the statement of counsel for Defendant as to position of Judge Advocate was read into record. Morris then stated that except for rumor, he had no knowledge ofthe facts nor the government witness, and was given an adjourment to Feb. 4. Morris read, on Feb 4th, a letter from B.F. Butler and Chas. O'Connor "members of New York Bar, employed by relatives of Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, one of the persons for the murder of whom Mackenzie is on trial" requesting permission to be present and to participate in the proceedings. The request was denied by the Court. The Government presented several witnesses from the ship's officers and crew who established that Philip was placed in the Ward Room of the Sommers, handcuffed and in leg irons, the evening of 26 Nov 1842; that a day or two later Cromwell and Small were locked up with him; and that on the morning of 1 Dec 1842, all three were brought on deck and executed by hanging. The defendant then presented numerous witnesses of the ship's officers and crew for the purpose of establishing that the summary executions were justified, alleging guilt of Philip of mutiny and that time and circumstances did not permit bringing the three back to the United States for the court martial they had been lead to believe they would recieve. The "direct" evidence of mutinyc onsisted of the testimony of Purser's Steward Wales. Wales stated Philip approached him the evening of Nov 25, 1842, got him up on a boom where they would have privacy, placed Wales under another of secrecy, and then explained his plan to take over command of the Somers. Reportedly Philip was in league with about 20 of the Brig's company; who intended to murder all her officer, and commence pirating. Philip said he had plans drawn up on a paper in his neckerchief (felt by Wales); that Philip said some night when Philip had the midwatch, a "scuffle" would be started on the forecastle. Philip would cause participants to be brought to the Mast; that Mr. Rogers, Officer of Deck, would be called to "settle" the matter, where-upon Rogers would be seized and pitched overboard. Philip would then murder the Commander; then go to the War Room and kill officers there; return to deck and have two after guns slewed round to rake the deck; call the crew on deck; select mates for operation of ship; proceed to Cape St. Antonie of the Isle of Pines, where a conspirator would be taken on board, and then commence cruising for prizes. Philip reportedly had ideas, but not advanced plans, of taking over the ships he had been previously on. The other direct evidence was the "Greek Letter" paper found in Philip's razor case. Philip, when place in irons, told the Commander the plan was a joke. The Commander relied largely on the reported conduct of the crew to support his conclusions that summary execution was necessary. A mast or its gear feel on deck under a heavy sea the night after Philip's arrest and the noise and running of the crew on deck created the impression the mutiny was under way. Discipline on the ship had been good, until the departure from Cape Meservado. Philip had fraternized with the crew, rather than with fellow officers, giving them tobacco and candy against the Commander's orders; and Philip had displayed contempt fo the Commander. After Philip's arrest, the crew gathered in groups and talked among themselves, but dispersed when officers approached. When notified, just a few minutes before the execution and with nooses around their necks, Philip had asked the Commander if he was not acting hastily. Cromwell and Small had reportedly blamed Philip for their plight. Following the execution, the crew was asked to give three cheers for the flag, and discipline was returned. The commander reportedly had asked his officers what action they would take in his position. They gave him a written statement for immediate execution. At the court, they expressed the opinions that while not more than 14 of the crew members listed by Philip would have taken part in the porposed mutiny, that the mutiny against acrew of 120 would have been successful; that the ship did not have accomodations for additional prisoners, there for these three should be disposed of; and that the remaining officers could not have stood up under the burden of keeping watch on the ship and prisoners until the ship arrived at St. Thomas or a U.S. port. Ref: Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy)--Records of General Courts Martial and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department 1799-1867, M-273, Roll 49. In an old Chi Psi song, two of its many verses praise Spencer; O here's to Philip Spencer Who when about to die When sinking down beneath the waves Loud shouted out Chi Psi! So, fill your glasses to the brim, And drink with manly pride Humanity received a blow When Philip Spencer died. Shortly after noon,on December 1, 1842, three hooded, manacled figures were hoisted to the main yardarm of the U.S. Brig-of-War Somers. The captain, as was his wont in such an emergency, deleivered a pious homily to the remaining 117 men and boys, many of whom were weeping. The Stars and Stripes was raised. Then the crew gave three cheers for the American flag and were piped down to dinner, leaving the bodies of Boatswain's Mate Samuel Cromwell, Seaman Elisha Small, and Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer--the son of the Secretary of War--to swing in the rising wind. After dinner, under the personal direction of the captain, always as tickler for form, the three bodies were elaborately prepared for burial; at dusk they were ceremoniously lowered into the sea. Thus ended the only recorded mutiny in the United States Navy--if mutiny it was. Fifteen days later the Somers dropped anchor in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, still carrying eleven prisoners. The story was soon common gossip in New York City, whereupon the Captain of the ship, Commander Alexander Slidell MacKenzie, U.S. N., was wildly acclaimed as a hero. Horace Greeley led the applause, "By the prompt and fearless decision of Captain MacKenzie", he wrote in his New York Tribune, "one ofthe most bold and daring conspiracies ever formed was frustrated and crushed". In his initial report on the trouble to Secretary of the Navy, Abel P. Upshur, MacKenzie described conditions aboard the Somers as approaching a state of imminent peril; a plot to seize control of the ship, head her into the Isle of Pines off the coast of Cuba, and turn pirate had been foiled. Philip Spencer was the ringleader; Cromwell and Small his loyal cohorts. Those crew members who wanted to join forces with the mutineers were to have been retained; the rest, including all the officer, were to have been murdered. Only prompt and severe measures by MacKenzie had saved the ship. The plot had been uncovered on the night of November 25 by the purser's steward, James W. Wales, whom Spencer approached to join the conspiracy. Next morning Wales told the purser, who in turn reported to the brig's lieutenant, Guert Gansevoort. Gansevoort rushed to the Captain with the story. MacKenzie at first ridiculed the possiblility of a mutiny, but on second thought he took a graver view. As a precaution, Spencer was put in irons on deck and forbidden to communicate with the crew. A list written in the Greek alphabet was found in Spencer's locker, which when translated named those crew members who were surely in the plot; those who might collaborate; and those who would have to be held against their will. Another piece of paper contained the specific assignments of the plotters at the moment of the mutiny. Small was mentioned twice on the lists, Cromwell not at all. Nonetheless, both men were confined on November 17. Tension mounted. The officers stood round the clock armed patrol. The crew went sullenly and anxiously about their business. During the night (of Tuesday the 29th) seditious wordswere heard through out the vessel, MacKenzie wrote later. Various intelligence was obtained from time to time of conferences. ..Several times during the night, there were symptoms of an intention to strike some blow. (At no point, however, were these words or actions ever specified). Further doubts had assailed the Captain: What if other mutineers were at large? Four more of the crew were taken into custody the next morning. By Wednesday several officers had concluded that seven prisoners on deck would impede the operation of the ship----an opinion which forced decision on what to do with the orginal three. At this juncture MacKenzie formally asked his officers for their joint counsel, after taking "into deliberate and dispassionate consideration the present condition of the vessel. . ." The officers formed themselves into a court of inquiry which lasted into the following day. At length, prodded by MacKenzie, they announced that they had come "to a cool, decided and ananimous opinion that they (Spencer, Cromwell, and Small) have been guilty of a full and determined intention to commit a mutiny on board of this vessel of an atrocious nature and that the revelation of circumstances having made it necessary to confine others with them. . .we are convinced the safety of the public property, the lives of ourselves and of those committed to our charges require that. . .they should be put to death, in a manner best calculated. . .to make a beneficial impression upon the disaffected. No time was lost in reflection; the sentence was executed within two hours. MacKenzie certainly believed his command and his crew to be in danger. And had Philip Spencer not been the son of John Canfield Spencer, then President Tyler's Secretary of War, MacKenzie's story might have well gone unchallenged. But on December 21, a letter in the New York Tribune (later attributed to the elder Spencer) pointed out that by MacKenzie's own report, "the men were hanged when everything and person were perfectly quiet after four days of perfect security". No mutinous act had occurred in that interlude. This document set in motion a whole new line of inquiry. Many who had at first supported MacKenzie now reversed themselves and found the triple execution to be "a high-handed and unnecessary measure" When the preliminary naval court of inquiry failed to censure the Captain, such a halloo arose for a grand jury investigation that the Navy, anxious to protect its own, rather reluctantly arranged a court-martial for MacKenzie. He was acquitted, but the story that unfolded there could scarcely evoke the same verdict for history. As the omissions, embellishments, contradictions, and down right lies were sifted,the Somers tragedy emerged as the tale of mass hypnotic terror; of craven weakness on the part of Captain MacKenzie; and of apathetic, juvenile bravura on the part of a maladjusted eighteen-year-old, Philip Spencer. The discrepancies that so aroused MacKenzie's contemporaries are even more apparent to anyone who looks at the record today. MacKenzie and his officersjustified their action on the grounds of impending danger. Yetthe newly commissioned Somers was no warship: it had been turned into a training vessel for juvenile recruits. Only six of the crew were over nineteen years of age; forty-five were under sixteen; three were only thirteen. The few older hands were expected to teach seamanship to the apprentices. This floating academy had left New York in September, bound for the African coast, and had returned to Caribbean waters by the time the trouble occurred. It could not have been a pleasant voyage. The Somers was built to accommodate ninety; she carried one hundred and twenty. Floggings were frequent. The smaller boys lived in terror of Boatswain's Mate Cromwell, a large, burly, bad-tempered man. As for Captain MacKenzie, it would have been difficult to find a man less equipped to condition young boys to a naval career. Medium-sized, red-haired, mild-mannered, he was a thirty-nine prim, severe, fussy, sanctimonious, humorless, vain, moralistic, vacillating in times of crisis, and above all,vastly inhuman. Many who sailed with him on that voyage were to desert the sea forever. His real aspirations were literary rather than nautical. Born Alexander MacKenzie Slidell, he revered his middle and surnames at the behest of a wealthy uncle who wished to perpetuate the Mackenzie line--and thereby inherited enough money to allow him to pursue a literary career on the side. He wrote six books and quantities of tedious, ifshorter, discourses; his pen was seldom still. It is worthnothing that MacKenzie's brother was John Slidell, the Confederate envoy to Britain who was snatched from the British steamer Trent by the Union Navy in 1861; his son, Ranold, became one of the most daring and successful Indian fighters in the history of the west. Due largely to the backing of his friend Washington Irving, MacKenzie's book, A Year in Spain, was an immediate success in both America and England. At twenty-nine he was mildly famous. His style was florid, but so was the era. The Navy was sufficiently impressed by this unaccustomed talent in its ranks to accord MacKenzie unusual consideration--though he was also a deligent and scrupulous officer. He rose rapidly to independent command, as much on the strength of his literary as his naval accomplishments. And this literary propensity stood him in good stead after the mutiny; during his various trials he wrote four versions of the affair, each longer than the last, and each containing new and fanciful embellishments; like a cuttlefish in danger, he defended himself by emitting blasks of ink. Philip Spencer came to the Somers with a tarnished reputation. A slouching, sullen boy with a mop of darkhair and a cast in one eye, he had managed thus far in life to make a mess of everything he had attempted. After spending three years as a recalcitrant freshman at Geneva 9now Hobart)College, he was thrust into Union college by his outraged,domineering, short-tempered father, a lean and hard man with eyes "fierce and quick rolling", and a face bearing "an unpleasant character of sternness". Here Spencer remained long enough to help found the Chi Psi fraternity, which still toasts him in its rituals. A further brush with the authorities landed him in the Navy, after a final warning from his father that disinheritance would follow should he fail once more. He was commissioned an acting midshipman in November, 1841, joining a squadron off Brazil. He began to drink heavily and was shipped back to New York in disgrace in July, 1842. Once again he got another chance--his last. Through his father's intervention he was restored to his rank, boarding the Somers two weeks later. No one could have appealed less to the prissy, fastidious MacKenzie. Nor did Spencer get on with his fellow officers, most of whom were hand-picked proteges of the Captain. Nowunnaturally, this lonely, defieant outcast of eighteen turned tothe crew for companionship, and inwardly conjured up grandiose dreams of glory and revenge as a solace to this ego. Spencer alternately bought and clowned his way to popularity with the crew. He bribed Waltham, the Negro wardroom steward, to steal brandy for him and the bibulous Seaman Small, and went into hock for then pounds of tobacco and over seven hundred cigars, largely for Cromwell (these despite MacKenzie's sharp disapproval of tobacco and his conviction that "the drinking of brandy is even more dreadful than malaria". Spencer could be seen at odd hours, joking with the men, cutting capers for the boys, throwing coins on the deck like an emperor and watching the rabble scramble for them. He had a trick of dislocating his jaw and by "contact of the bones" producing tunes "with accuracy and elegrance", which threw his audience into raptures. Spencer's scarcely concealed contempt for MacKenzie behind his back (although he was careful to be civil face to face) further endeared him to the crew. Small and Cromwell, his chief cronies,were hardly desirable companions for an unstable boy. Small had lost most of his berths through drink, Cromwell at various times had been both a slaver and a pirate. It is not clear why thesetwo seafaring hobos should have been chosen to train young, inexperienced recruits (MacKenzie, in a peculiarly macabre gesture, was to delay burial of the three mutineers for an hour to have Cromwell's head shaved. The scars of violence revealed thereon some how assured the Captain of the wisdom of his course). No doubt in payment for liquor and cigars, these two men regaled Spencer with tales of a lurid past, real or fancied. Always addicted to blood and thunder thrillers, he evidently began to brood on the delicious possibilites of a life of priacy---with its rich treasure, daring forays, beautiful women--and himself, a well-beloved by awe-inspiring hear, in full command. Whether two such seasoned hands as Small andCromwell ever took him seriously, or whether they simply played up to him for hand outs, is not known. There is nothing on the record, in fact, to indicate that Cromwell had even heard of the plot. The purser's steward, James Wales, was the first to report that a mutiny was in the making. Yet later inquiry revealed that the plump, sly "Whales" was in bad odor with MacKenzie at the time because of some unspecified shady transaction in Puerto Rico. It took little intelligence to see that Philip Spencer was MacKenzie's bete noire, and any derogarogy information about himmight well boast the sagging stock of any informant. MacKenzie did in fact advance Wales to the rank of acting midshipman after Spencer's death and recommended that the rank be made permanent. No one knows how true Wales' report of a mutiny was, and no one made the slightest attempt to find out. From that moment on, the conduct of MacKenzie and his officers seems at best indefensible; despicable is a more accurate term. Instead of making sober inquiry into the facts, they subcumbed to unconcealed hysteria. The first and obvious step was to examine Spencer. Yet Spencer was only twice questioned. Once casually on the twenty-sixth before his arrest, and again just an hour before his death, at which time the miserable boy admitted that plotting mutinies "had become a mania with him", a childish sort of game. The noose was strong punishment for this troubled adolescent. Spencer, having originally been told that he would be taken to New York for trial, bore himself well in confinement. But the sight of him and his fellow lying in fetters apparently did nothing to allay the mounting fears of the officers. A top gailant mast snapped. MacKenzie read dark meaning into this common accident. Seamen swarmed to repair the damage, and he later noted, "all those who were most conspicuously named int he program of Mr. Spencer. . .mustered at the main topmast head.' Withal, he reports no suspicious act, no hostile words. Only his fears led MacKenzie to arrest Cromwell. When the new prisoner was brought to where Spencer sat hunched in his double irons. It was Spencer who volunteered the information (as he was to do twice more before the end) that Cromwell was innocent. "I doubt if Cromwell could have been enlisted in any such enterprise, unless there was money aboard," he said a little bitterly. Guilt by association was the only charge leveled agains Cromwell. He was condemned solely on Wales's surmise that he might have been involved because he was often seen in Spencer's company, and because Lieutenant Gansevoort later confided, "I don't like Cromwell's looks". And so it went for five terrible days. Each tiny incident of normal shipboard life was blown up to the bursting point. A midshipman herded a clean-up crew out of the twilight toward the officer's quarters ostensibly to man the mast rope in raising a new spar. The overwrought Gansevoort cried, "Halt, I say! I'll blow out the brains of the first man who steps on the quarter-deck". The midshipman had to rush to the front of his quivering group and explain himself. At any point those interested in mutiny might have rushed the officers and freed their comrades, yet no one made the slightest move to help the prisoners. The chances are that no one cared to; even Small was heard to mutter thatSpencer was a little crazy. On the sixth day, the three men were hanged, although no single incident occurred that in any way further incriminated them. As MacKenzie explained later: "The deep sense I had of the solemn obligation I was under to protectand defend the vessel. . .the officers and the crew---the seas traversed by our peaceful merchantmen and the unarmed of all nations. . .from the horrors which the conspirators had mediated and, above all, to guard from violation the sanctity of the American flag"--the commander wrapped himself in the national ensign as habitaully as he put on his nightshirt--"all impressed on me the absolute necessity of adopting some further measures for the security of the vessel." The proceeding were a shabby farce. MacKenzie later admitted that the kangaroo court of officers was assembled after he and Gansevoort had privately made up their minds to execute the prisoners. The court had no chairman, and the notes of its secretary were sketchy at best. The obvious people to examine--the three prisoners--were never called. But thirteen other witnesses did appear. One of them, later a prisoner himself, described the procedure: "Before a question of one officer was answered, other would be put by other officers, thus not only confounding the person being examined but themselves". A witness was told just to sign a statement--his answers would be filled in later. None of the information represented anything but hearsay and wild suppositions. A typical response: "I don't think the vessel is safe with these prisoners aboard. This is my deliberate opinion from what I heard King, the gunner's mate say: that is, that he had heard the boys say there were spies about". Afterward,MacKenzie saw to it that the faithful were rewarded. Seven ofthe witnesses were recommended for advancement. And it is worthy of note that during MacKenzie's own subsequent court-martial, when every effort was made to unearth supportingevidence for his actions, no single person was found who had ever heard the word "mutiny" mentioned aboard the Somers before Spencer's arrest. . .But they were hanged anyway, and on February 1, 1843, on a ship in New York Harbor Alexander Slidell MacKenzie was brought before a court-martial to defend himself. His own court-martial gave MacKenzie every leeway. He did not testify in his own behalf, thus saving himself from the hazardof cross-examination. Instead, he was allowed to present written explanations of the points raised by the timid, fusty little prosecutor. While MacKenzie sat resplendent in dress uniform day after day (he donned it on the slightest provocation), his loyal cohorts rehearsed the cooperative members of the crew until they had their stories letter-perfect.The less reliable were allowed to desert. The eleven prisoners were eventually freed without charge. New York grew bored and turned to more lively topics, a quiet acquittal became inevitable. The most seraching questions were asked by a man who had no connection with the case. And the answers he offered make MacKenzie out part fool, part coward, part arrant knave. No less a personage than James Fenimore Cooper, himself an ex-midshipman in the Navy, carried the case to the public. Why he entered the controversy is not exactly certain. Disputatiousby nature, and frequently involved in litagation, Cooper was a constant supporter of causes. Perhaps he simply hated the injustice of the affair or the sanctimonious behavior of MacKenzie. Or possibly, himself expelled from Yale, defiant of authority, and an ex-Navy man aware of the brutality of the fleet, Cooper identified himself with Spencer, whose life roughly paralleled his own early experience. MacKenzie had presented four prime reasons why the prisoners had perforce to forfeit their lives: First, the size and construction of the brig made it vulnerable. The prisoners had been held on deckbecause MacKenzie feared that they could not have been safely kept below. The partitions, he claimed, were so frail that they might have been forced. Cooper thought that an extremely farpfetched assumption. On the contrary, he suggested, the size of the Somers actually favored the officers. If there was real trouble, "twenty, or even ten armed men on the quarter-deck of abrig of 66 tons make them a very formidable array as opposed to any number of unarmed, or even armed men that could approach them at a time" Furthermore, her size was an asset from another point of view. "We see nothing to have prevented Captain Mackenzie from sending all but his officer below and of carrying the brig across the ocean, if needed, with the gentlemen of the quarter-deck alone." Under such circumstances, "even admitting a pretty widespread disaffection", the chances were nine out often in favor of her officers, "and that risk might have been run before an American citizen was hanged without trial". To MacKenzie's report that each night's darkness added to the peril on board the Somers; Cooper answered that there was no necessity for darkness, for every man-of-war had means of lighting her own decks. Second, MacKenzie cited "the sullenness, the violent and menacing demeanor and portentous looks of the crew". Cooper rejoined, "We entertain no doubt that much the great portion of the ominous conversation groupings, shaking of the head and strange look. . had their origin in the natural wonder of the crew at seeing an officer in this novel situation. . .The Somer had. . .at least 30 more than she should have had--and it is scarcely possible that with her boats bestowed and one third of her deck reserved for her officers, one hundred men could be on her remaining deck wihout being in "Knots". Third, though it had been suggested by some of the officers that the prisoners be landed at St. Thomas, in the Virgin Islands, MacKenzie had refused becaused he claimed it would have been virtual admission that the mutiny was beyond the control of the ship's authority. Cooper pointed out that since men-of-war often sought protection in a friendly port from starvation or disease, why not from mutineers? Fourth, MacKenzie said his officers were exhausted by the emergency watch and watch routines. Cooper ridiculed this assertion. What was there to cause all this exhaustion?Thousands were on watch and watch at night for long voyages".∼Phillip Spencer was the son of Secretary of War John C. Spencer, and was one of three hanged without court-martial, aboard the USS Somers for conspiracy to mutiny. The subsequent execution, and burial at sea of Spencer, and the two others is cited as the reason for the forming of the Naval Academy. It is believed that the Somers Affair is the only documented attempt of mutiny aboard a U.S. Naval ship. The Somers Affair, as it was later known, is the model for the Herman Melville novel Billy Budd. Melville is the cousin of Lt. Guert Gansvroot, an officer stationed on the Somers during the attempted mutiny.

Edited Text from Roger Jones Find a Grave ID 47311489;

Only U.S. Midshipman hung for mutiny in the Navy.

Philip first attended Hobart College, transferred to Union College but left after 6 months and through the influence of his father, John Canfield [Spencer], was placed as a midshipman on the brig-of-war, "Somers". Upon the return from a cruise, it was learned that Philip, then 19 years, and 2 seamen, had been hanged, 1 Dec 1842, for mutiny.

[From Microphoto M-330,"Abstracts of the Service Records of Naval Officers", Roll 6, No. 2166, National Archives, Washington, DC Philip Spencer--20 Nov 1841 Nov. 39 '41 to Resq (?) S at 5 St. Y.C. 462 Feby 7th'42 to the John Adams 566 21 Jul 1842 retd by the Potomac fr. Bowfish. Augt. 13th to the Somers 216 Died on board the Brig. Somers 1 Dec 1842.

Salute for Chi Psi Martyr Union College of Schenectady, NY, claims the title "mother of fraternities" because there, about a century ago, were organized six of the earliest Greek-letter societies. Last week one of them, Chi Psi, which calls its chapter alphas and its houses lodges, summoned 600 of its 300 members from all over the nation to Union for a celebration of its centennial. The name of Philip Spencer dominated proceeding. To Union's library the fraternity ceremonially presented a Chi Psi Alcove of 600 books on human relations and above it a portrait of Philip Spencer. At a banquet, John Wendell Anderson, Detroit lawyer and former Chi Psi president, gave the society $100,000 as the nucleus of a Spencer memorial trust fund to help the 25 active alphas payoff mortgages on lodges. This Philip Spencer was the son of John C. Spencer, President Tyler's Secretary of War. In 1841, when the prankish youth was fired from Hobart College of Geneva, NY, for neglecting his studies, he shifted to Union and promptly leagued with nine other students to create Chi Psi. Then, after six months, he quit Union, joined the Navy, and got a berth as acting midshipman aboard the brig Somers. One day in 1841, the Somers arrived in NY from Africa with shocking news: The 19-year-old Cabinet member's son and two other crewmen had been hanged at sea for mutiny. Comdr. Alexander MacKenzie insisted he had found on Spencer a list, in Greek letters, of potential accomplices and that the youth had confessed. In the furor that followed the writer James Fenimore Cooper charged that the Greek writing concerned Chi Psi and that Spencer had died guarding fraternity secrets. However, MacKenzie was court-martialed and acquitted. So, the Somers incident, recorded in naval history as a thwarted mutiny is revered by Chi Psi as a fraternal martyrdom.

[Ref: Newsweek, 12 May 1941, p.76. McKenzie, A. Slidell, No. 844, Commander, tried 28 Dec 1842; charges "Executions on board the US Brig Somers"; Sentence: "court of Inquiry" Statement of facts: with opinion that Commander McKenzie and officers honorably performed their duty to the service and their country". "Murder, --oppression--illegal punishment conduct unbecoming an officer--cruelty and oppression"; Sentence "Acquitted". Action of President or the Department "confirmed". A.P. Upshur. Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy)--Records of General Courts Martial and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department 1799-1867, M-273, Roll 1.]

The Court Martial convened aboard the USS North Carolina, New York, 1 Feb 1843, and continues through over 600 pages of the proceedings through the acquittal findings and decision of 28 Feb 1843. The excerpt from the logbook of the Somers states: "We left New York on the 12th of September 1842 civil time, arrived at Funchal Oct 5, 1842, arrived at Santa Cruz Oct. 8, 1842, arrived at Porto Praya Oct 21, 1842, arrived at Cape Meservado Nov 10, 1842, arrived at St. Thomas, Dec. 5, 1842; arrived at New York Dec 15, 1842." W. H. Morris, Esquire, of Baltimore had been appointed Judge Advocate by the Navy Department letter of 25 Jan 1843, signed by A. P. Upshur. The court was composed of officers. On 2 Feb 1843, Commander Alex R. Slidell Mackenzie pleaded, in writing, as follows: "I admit that Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, Boatswain mate Samuel Cromwell, and Seaman Elisha Small were put to death by my order as Commander of the U.S. Brig Somers, at the time and place mentioned in the charges, but as under the existing circumstances this act was demanded by duty and justified by necessity, I plead not guilty to all the charges." Morris read a statement of his conception of his responsibilities in this 'civil proceeding', requested a statement from defense as to its intended procedure so Morris could determine his course of action, saying, "This is thought by Government to be a case of great importance and it is not unlikely that an associate of masterly ability and whose capacity has been enabled by age to command the respect of the whole country may be sent to me as a coadjutor." On 3 Feb 1843, the statement of counsel for Defendant as to position of Judge Advocate was read into record. Morris then stated that except for rumor, he had no knowledge ofthe facts nor the government witness and was given an adjournment to Feb. 4. Morris read on Feb 4th, a letter from B.F. Butler and Chas. O'Connor "members of New York Bar, employed by relatives of Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, one of the persons for the murder of whom Mackenzie is on trial" requesting permission to be present and to participate in the proceedings. The request was denied by the Court. The Government presented several witnesses from the ship's officers and crew who established that Philip was placed in the Wardroom of the Sommers, handcuffed and in leg irons, the evening of 26 Nov 1842; that a day or two later Cromwell and Small were locked up with him; and that on the morning of 1 Dec 1842, all three were brought on deck and executed by hanging. The defendant then presented numerous witnesses of the ship's officers and crew for the purpose of establishing that the summary executions were justified, alleging guilt of Philip of mutiny and that time and circumstances did not permit bringing the three back to the United States for the court martial they had been led to believe they would receive. The "direct" evidence of mutiny consisted of the testimony of Purser's Steward Wales. Wales stated Philip approached him the evening of Nov 25, 1842, got him up on a boom where they would have privacy, placed Wales under another of secrecy, and then explained his plan to take over command of the Somers. Reportedly Philip was in league with about 20 of the Brig's company, who intended to murder all her officer, and commence pirating. Philip said he had plans drawn up on a paper in his neckerchief (felt by Wales); that Philip said some night when Philip had the midwatch, a "scuffle" would be started on the forecastle. Philip would cause participants to be brought to the Mast; that Mr. Rogers, Officer of Deck, would be called to "settle" the matter, where-upon Rogers would be seized and pitched overboard. Philip would then murder the Commander; then go to the War Room and kill officers there; return to deck and have two after guns slewed round to rake the deck; call the crew on deck; select mates for operation of ship; proceed to Cape St. Antonie of the Isle of Pines, where a conspirator would be taken on board, and then commence cruising for prizes. Philip reportedly had ideas, but not advanced plans, of taking over the ships he had been previously on. The other direct evidence was the "Greek Letter" paper found in Philip's razor case. Philip, when place in irons, told the Commander the plan was a joke. The Commander relied largely on the reported conduct of the crew to support his conclusions that summary execution was necessary. A mast or its gear feel on deck under a heavy sea the night after Philip's arrest and the noise and running of the crew on deck created the impression the mutiny was under way. Discipline on the ship had been good, until the departure from Cape Meservado. Philip had fraternized with the crew, rather than with fellow officers, giving them tobacco and candy against the Commander's orders; and Philip had displayed contempt fo the Commander. After Philip's arrest, the crew gathered in groups and talked among themselves, but dispersed when officers approached. When notified, just a few minutes before the execution and with nooses around their necks, Philip had asked the Commander if he was not acting hastily. Cromwell and Small had reportedly blamed Philip for their plight. Following the execution, the crew was asked to give three cheers for the flag, and discipline was returned. The commander reportedly had asked his officers what action they would take in his position. They gave him a written statement for immediate execution. At the court, they expressed the opinions that while not more than 14 of the crew members listed by Philip would have taken part in the proposed mutiny, that the mutiny against a crew of 120 would have been successful; that the ship did not have accommodations for additional prisoners, there for these three should be disposed of; and that the remaining officers could not have stood up under the burden of keeping watch on the ship and prisoners until the ship arrived at St. Thomas or a U.S. port. Ref: Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy)--Records of General Courts Martial and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department 1799-1867, M-273, Roll 49. In an old Chi Psi song, two of its many verses praise Spencer:

O here's to Philip Spencer Who when about to die

When sinking down beneath the waves Loud shouted out Chi Psi!

So, fill your glasses to the brim, And drink with manly pride

Humanity received a blow When Philip Spencer died.

Shortly after noon, on December 1, 1842, three hooded, manacled figures were hoisted to the main yardarm of the U.S. Brig-of-War Somers. The captain, as was his wont in such an emergency, delivered a pious homily to the remaining 117 men and boys, many of whom were weeping. The Stars and Stripes was raised. Then the crew gave three cheers for the American flag and were piped down to dinner, leaving the bodies of Boatswain's Mate Samuel Cromwell, Seaman Elisha Small, and Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer--the son of the Secretary of War--to swing in the rising wind. After dinner, under the personal direction of the captain, always as tickler for form, the three bodies were elaborately prepared for burial; at dusk they were ceremoniously lowered into the sea. Thus ended the only recorded mutiny in the United States Navy--if mutiny it was.