Early in the War

When the first American troop convoy sailed for France in June 1917, no black Soldiers were aboard. The 400-500 uniformed black stevedores aboard were technically civilians but were still subject to military rules and regulations. They were assigned the worst berthing and mess facilities aboard ship. Many preferred sleeping on deck, regardless of weather, rather than in the stuffy lower decks where they were assigned. The black officers assigned to supervise them were not allowed to dine in the white officers' mess, but black men were assigned there to serve as mess boys and stewards. (1) Stevedores were often disdained because of the common belief among white officers and Soldiers that they were physically or mentally inferior and unfit for combat.

Toward the end of the war, civilian laborers were replaced by the Services of Supply. The black Soldiers who made up one-third of that group were organized into 46 engineer service battalions, 44 labor battalions, 24 labor companies, and more than a dozen pioneer infantry regiments. These units built base camps, docks and piers, supply sheds, storage areas near ports and railroad facilities, and barracks and temporary housing for troops who were pushed from the ports to the front lines. Some Soldiers became forestry engineers, felling trees and operating sawmills for fuel and construction projects. In 20 days, the 335th Labor Battalion cut more than 1,000 cubic meters of wood and 250,000 poles and then dragged the results out of the forest with sling ropes. The 331st Labor Battalion cut more than 40,000 cubic meters of wood in 108 days. While performing these duties, the men generally slept in floorless tents and ate outside in the rain and mud. Other black laborers quarried rock and stone for road and building repair and construction. Other laborers built or repaired damaged rail lines.

Pioneer infantry regiments fared better than stevedores and black labor units because they received infantry training in case they needed to fight on the front lines. Formed to support engineer regiments or provide engineer support to infantry and artillery units, pioneer infantry units usually had numerous mechanics, blacksmiths and farriers (important to an army still dependent on horses), and carpenters, plus a mixture of Soldiers with technical training from civilian schools. Many of the black pioneer infantry units worked close to the front lines and very often came under fire, accomplishing whatever missions they were assigned. They were engaged in road construction, trench construction and reinforcement, demolition work, and ammunition holding area construction. Before the armistice, several regiments were employed just behind the front lines at the Argonne Forest and Saint-Mihiel, where they constructed macadam roads and narrow-and wide-gauge railroads to transport artillery, supplies, and munitions. The 805th Pioneer Infantry Regiment was rushed in to repair a road near Varenne, which had been heavily damaged by German artillery fire. Without its repair, no ammunition could be transported forward to continue the American effort, nor could the wounded be evacuated for medical care. It is reported that this unit sang as it worked through the night with enemy artillery shells falling nearby to make the road passable. Seven of the black pioneer infantry regiments were authorized to wear the combat ribbon at war's end. (2) Many of the Soldiers of the pioneer infantry regiments, however, were disappointed in how their units were employed. As one officer lamented, "They did everything the infantry was too proud to do and the engineers too lazy to do." (3)

Under Fire

The 317th Engineer Regiment was formed on 24 October 1917 at Camp Sherman, Ohio. It would provide the combat engineering support for the all-black 92d Infantry Division. After careful consideration, the War Department inducted the 1,490 men into the regiment. It was composed of many men with experience in the construction trades and training at technical schools. There was much debate in the War Department about the officers who would command the unit. African-American officers who had graduated infantry training were suggested, but the Engineer Corps opposed this proposal because the officers lacked specific engineer training. In the end, 30 black infantry officers were assigned to the unit, three of whom had engineering experience and education. After arriving in France, the black captains (except the chaplain, two line officers, and those in the medical detachment) were replaced by white officers, but the black lieutenants were retained.

The unit sailed for France on 8 June and reached Brest on 19 June. The Soldiers were immediately put to work loading baggage headed for the front and working on roads and barracks. At the port of Saint-Nazaire, the regiment almost single-handedly built a pier that stretched a mile offshore. It was very dangerous work since the Soldiers had to work standing on slippery boards. On June 27, the regiment arrived in the Bourbonne-les-Bains for 4 weeks of intensive training and work on projects such as building mess halls, shower facilities, barracks, stables, warehouses, and railroad yards. The regiment became the first element of the 92d Division to enter the war, relieving the 7th Engineers, 5th Infantry Division, in late August. They constructed dugouts, repaired and extended trenches, and mined bridges that were in danger of falling into enemy hands. They also engaged in lumber and sawmill operations, providing firewood and lumber for construction projects. In one mission, 25 enlisted men performed especially courageously under fire for 3 days and nights, gas-proofing dugouts as enemy artillery fired phosgene and mustard gas on their positions.

From the time the U.S. Army launched its greatest attack of the war in the Argonne Forest on 26 September 1918 until the conclusion of hostilities on 11 November, the regiment worked tirelessly to open major roads to support the effort. In many places, the roads had been destroyed by enemy fire and required massive amounts of labor and materials to repair. Often, the roads had to be rerouted at night through less-than-ideal terrain and reinforced with logs to evacuate casualties and to ensure that supplies and ammunition reached the front lines. The men salvaged rocks and timbers from abandoned and mined enemy positions and used them to reinforce trenches for the Americans. They also built light-gauge railroads to supply forces at the front lines and heavy-gauge railroads to move troops and supplies in the rear areas. They worked day and night throughout the offensive, often under enemy fire, earning unit campaign streamers for the Meusse-Argonne and Lorraine Campaigns. After the war, the 317th was demobilized on 31 March 1919.

After the Armistice

Despite their distinguished service, other slights awaited African-American Soldiers after the armistice of 11 November 1918. They were excluded from many victory parades, including the main parade in Paris, despite the fact that black troops from England and France were included. The huge French war painting, "Le Pantheon de la Guerre," by Pierre Carrier-Belleuse and Auguste Francois Gorguet, pictured those who had contributed to the final victory, including black soldiers of the Allied nations-except the Americans. It was as if the Army was unwilling to recognize the sacrifices and triumphs of its black warriors. (4)

After the fighting, much work remained and much of it fell to the African-American Soldiers and engineers. Some of the work was labor-intensive, such as constructing the Pershing Stadium near Paris, providing firewood, salvaging equipment and materials from the battlefields, removing barbed wire entanglements, detonating unexploded ordnance, and filling trenches. American cemeteries had to be constructed, the largest of which (Argonne National Cemetery) was established at Romagne. The task of retrieving decomposing bodies for burial in the cemeteries fell to the men of the black 814th, 815th, and 816th Pioneer Infantry Regiments. They retrieved and buried fallen Americans within a 50-kilometer radius of the cemetery. No doubt, the taboos associated with handling the dead added to their feelings of isolation, discrimination, and humiliation.

After the war, most Soldiers simply wished to put this chapter behind them and pick up with their civilian lives. However, many desired to continue their military service. As the Army drew down after the war, examining boards determined who would be retained on active duty. It seemed that the Army was intent on restricting the number of black officers and Soldiers allowed to continue military service. The few black officers who were retained found themselves restricted to infantry and cavalry units despite good performance as artillery and engineer officers. Black enlisted Soldiers could only reenlist in traditionally black regiments. (5) Interestingly, the 77th Engineer Combat Company was the last all-black unit to engage an enemy, some 30 years later in the Korean War. The Army was to remain segregated for many years, until Executive Order 9981 was signed by President Harry S. Truman in July 1948. The last surviving black World War I veteran, Mr. Moses Hardy, 805th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, died on 7 December 2006. With him passed the last opportunity to hear the story of the black engineers of the Great War from one who lived it. Although resources exist detailing the African-American experience in World War I, relatively few are dedicated to the engineers and the units that were assigned engineer roles.

Early in the War

When the first American troop convoy sailed for France in June 1917, no black Soldiers were aboard. The 400-500 uniformed black stevedores aboard were technically civilians but were still subject to military rules and regulations. They were assigned the worst berthing and mess facilities aboard ship. Many preferred sleeping on deck, regardless of weather, rather than in the stuffy lower decks where they were assigned. The black officers assigned to supervise them were not allowed to dine in the white officers' mess, but black men were assigned there to serve as mess boys and stewards. (1) Stevedores were often disdained because of the common belief among white officers and Soldiers that they were physically or mentally inferior and unfit for combat.

Toward the end of the war, civilian laborers were replaced by the Services of Supply. The black Soldiers who made up one-third of that group were organized into 46 engineer service battalions, 44 labor battalions, 24 labor companies, and more than a dozen pioneer infantry regiments. These units built base camps, docks and piers, supply sheds, storage areas near ports and railroad facilities, and barracks and temporary housing for troops who were pushed from the ports to the front lines. Some Soldiers became forestry engineers, felling trees and operating sawmills for fuel and construction projects. In 20 days, the 335th Labor Battalion cut more than 1,000 cubic meters of wood and 250,000 poles and then dragged the results out of the forest with sling ropes. The 331st Labor Battalion cut more than 40,000 cubic meters of wood in 108 days. While performing these duties, the men generally slept in floorless tents and ate outside in the rain and mud. Other black laborers quarried rock and stone for road and building repair and construction. Other laborers built or repaired damaged rail lines.

Pioneer infantry regiments fared better than stevedores and black labor units because they received infantry training in case they needed to fight on the front lines. Formed to support engineer regiments or provide engineer support to infantry and artillery units, pioneer infantry units usually had numerous mechanics, blacksmiths and farriers (important to an army still dependent on horses), and carpenters, plus a mixture of Soldiers with technical training from civilian schools. Many of the black pioneer infantry units worked close to the front lines and very often came under fire, accomplishing whatever missions they were assigned. They were engaged in road construction, trench construction and reinforcement, demolition work, and ammunition holding area construction. Before the armistice, several regiments were employed just behind the front lines at the Argonne Forest and Saint-Mihiel, where they constructed macadam roads and narrow-and wide-gauge railroads to transport artillery, supplies, and munitions. The 805th Pioneer Infantry Regiment was rushed in to repair a road near Varenne, which had been heavily damaged by German artillery fire. Without its repair, no ammunition could be transported forward to continue the American effort, nor could the wounded be evacuated for medical care. It is reported that this unit sang as it worked through the night with enemy artillery shells falling nearby to make the road passable. Seven of the black pioneer infantry regiments were authorized to wear the combat ribbon at war's end. (2) Many of the Soldiers of the pioneer infantry regiments, however, were disappointed in how their units were employed. As one officer lamented, "They did everything the infantry was too proud to do and the engineers too lazy to do." (3)

Under Fire

The 317th Engineer Regiment was formed on 24 October 1917 at Camp Sherman, Ohio. It would provide the combat engineering support for the all-black 92d Infantry Division. After careful consideration, the War Department inducted the 1,490 men into the regiment. It was composed of many men with experience in the construction trades and training at technical schools. There was much debate in the War Department about the officers who would command the unit. African-American officers who had graduated infantry training were suggested, but the Engineer Corps opposed this proposal because the officers lacked specific engineer training. In the end, 30 black infantry officers were assigned to the unit, three of whom had engineering experience and education. After arriving in France, the black captains (except the chaplain, two line officers, and those in the medical detachment) were replaced by white officers, but the black lieutenants were retained.

The unit sailed for France on 8 June and reached Brest on 19 June. The Soldiers were immediately put to work loading baggage headed for the front and working on roads and barracks. At the port of Saint-Nazaire, the regiment almost single-handedly built a pier that stretched a mile offshore. It was very dangerous work since the Soldiers had to work standing on slippery boards. On June 27, the regiment arrived in the Bourbonne-les-Bains for 4 weeks of intensive training and work on projects such as building mess halls, shower facilities, barracks, stables, warehouses, and railroad yards. The regiment became the first element of the 92d Division to enter the war, relieving the 7th Engineers, 5th Infantry Division, in late August. They constructed dugouts, repaired and extended trenches, and mined bridges that were in danger of falling into enemy hands. They also engaged in lumber and sawmill operations, providing firewood and lumber for construction projects. In one mission, 25 enlisted men performed especially courageously under fire for 3 days and nights, gas-proofing dugouts as enemy artillery fired phosgene and mustard gas on their positions.

From the time the U.S. Army launched its greatest attack of the war in the Argonne Forest on 26 September 1918 until the conclusion of hostilities on 11 November, the regiment worked tirelessly to open major roads to support the effort. In many places, the roads had been destroyed by enemy fire and required massive amounts of labor and materials to repair. Often, the roads had to be rerouted at night through less-than-ideal terrain and reinforced with logs to evacuate casualties and to ensure that supplies and ammunition reached the front lines. The men salvaged rocks and timbers from abandoned and mined enemy positions and used them to reinforce trenches for the Americans. They also built light-gauge railroads to supply forces at the front lines and heavy-gauge railroads to move troops and supplies in the rear areas. They worked day and night throughout the offensive, often under enemy fire, earning unit campaign streamers for the Meusse-Argonne and Lorraine Campaigns. After the war, the 317th was demobilized on 31 March 1919.

After the Armistice

Despite their distinguished service, other slights awaited African-American Soldiers after the armistice of 11 November 1918. They were excluded from many victory parades, including the main parade in Paris, despite the fact that black troops from England and France were included. The huge French war painting, "Le Pantheon de la Guerre," by Pierre Carrier-Belleuse and Auguste Francois Gorguet, pictured those who had contributed to the final victory, including black soldiers of the Allied nations-except the Americans. It was as if the Army was unwilling to recognize the sacrifices and triumphs of its black warriors. (4)

After the fighting, much work remained and much of it fell to the African-American Soldiers and engineers. Some of the work was labor-intensive, such as constructing the Pershing Stadium near Paris, providing firewood, salvaging equipment and materials from the battlefields, removing barbed wire entanglements, detonating unexploded ordnance, and filling trenches. American cemeteries had to be constructed, the largest of which (Argonne National Cemetery) was established at Romagne. The task of retrieving decomposing bodies for burial in the cemeteries fell to the men of the black 814th, 815th, and 816th Pioneer Infantry Regiments. They retrieved and buried fallen Americans within a 50-kilometer radius of the cemetery. No doubt, the taboos associated with handling the dead added to their feelings of isolation, discrimination, and humiliation.

After the war, most Soldiers simply wished to put this chapter behind them and pick up with their civilian lives. However, many desired to continue their military service. As the Army drew down after the war, examining boards determined who would be retained on active duty. It seemed that the Army was intent on restricting the number of black officers and Soldiers allowed to continue military service. The few black officers who were retained found themselves restricted to infantry and cavalry units despite good performance as artillery and engineer officers. Black enlisted Soldiers could only reenlist in traditionally black regiments. (5) Interestingly, the 77th Engineer Combat Company was the last all-black unit to engage an enemy, some 30 years later in the Korean War. The Army was to remain segregated for many years, until Executive Order 9981 was signed by President Harry S. Truman in July 1948. The last surviving black World War I veteran, Mr. Moses Hardy, 805th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, died on 7 December 2006. With him passed the last opportunity to hear the story of the black engineers of the Great War from one who lived it. Although resources exist detailing the African-American experience in World War I, relatively few are dedicated to the engineers and the units that were assigned engineer roles.

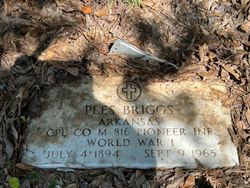

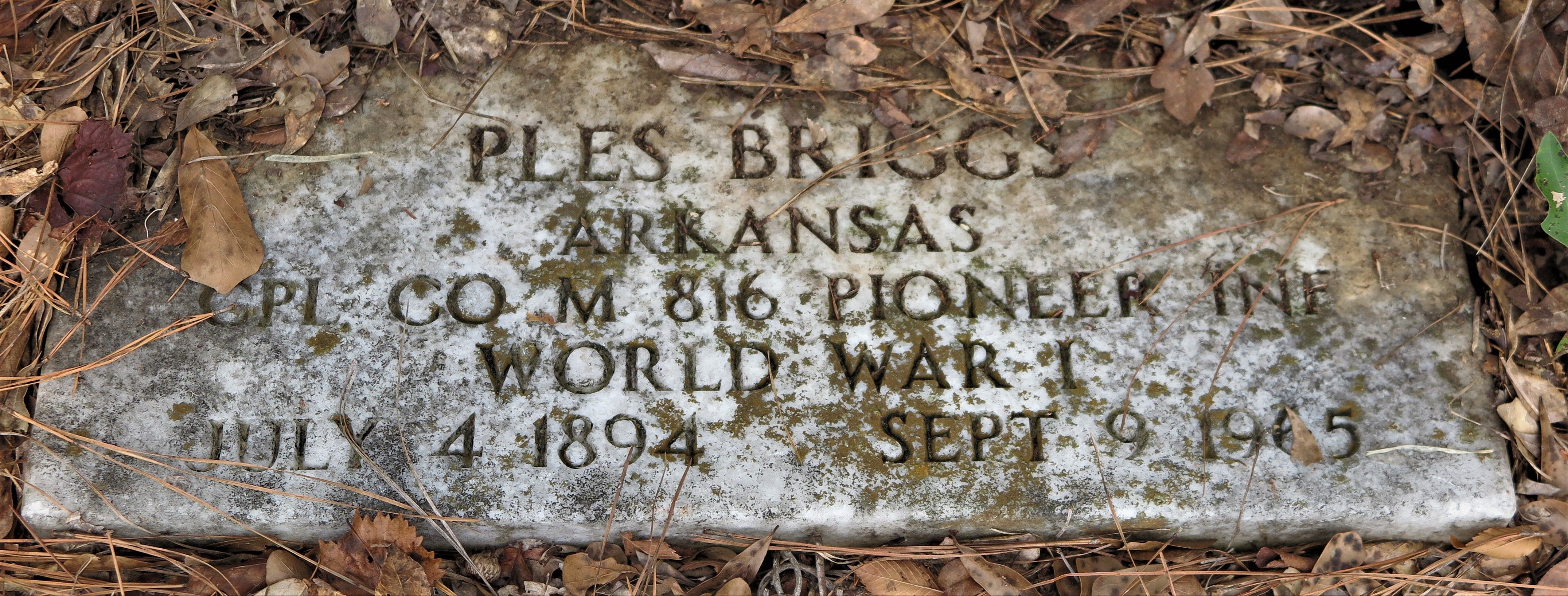

Inscription

Corporal 4th Class, US Army; 816th Pioneer Infantry - World War I

Family Members

-

![]()

Lillie Mae Briggs Mack

1901–1996

-

![]()

John Anderson Briggs

1902–1971

-

![]()

Augustus "Gus" Briggs

1904–1972

-

![]()

Rev William Theodore Briggs

1906–1986

-

![]()

Rowlet Briggs

1907–1973

-

![]()

Ernest Thurman Briggs

1909–1949

-

![]()

Mary Ophelia Briggs

1911–1992

-

![]()

Opal Inez Briggs Richardson

1916–2011

-

![]()

Arthur Lee Briggs

1918–1977

-

![]()

Henderson Briggs

1921–1980

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement