By

Robert Girard Carroon, PCinC

Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the U.S.

23 Thompson Road

West Hartford, CT 06107

[email protected]

(October 1998)

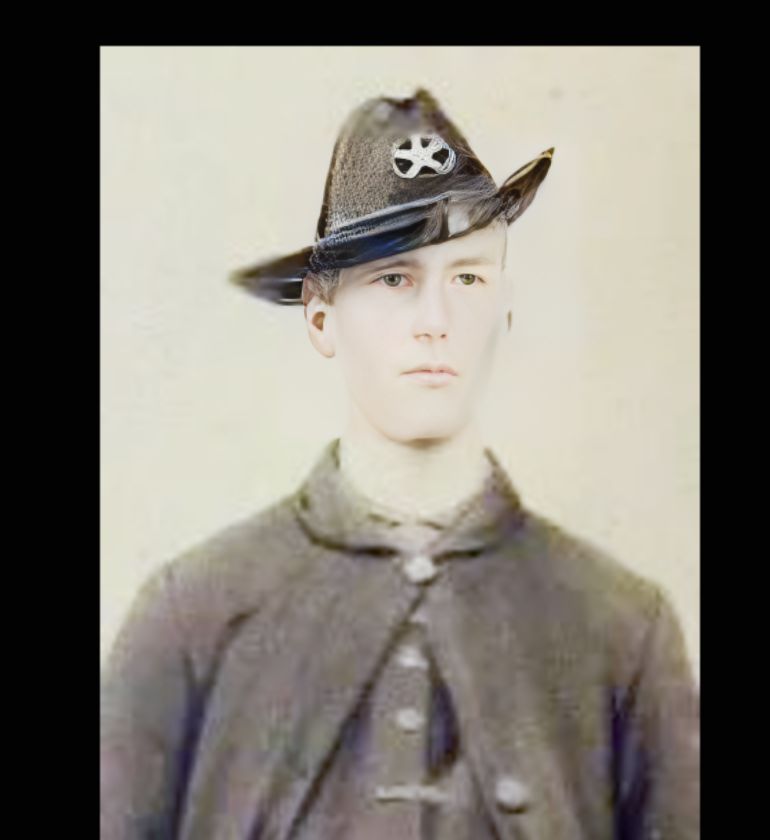

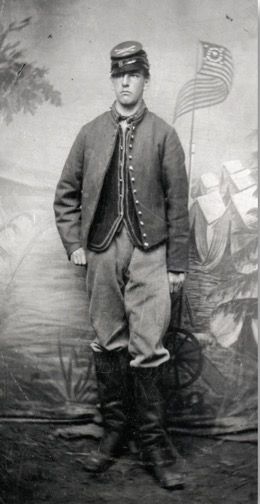

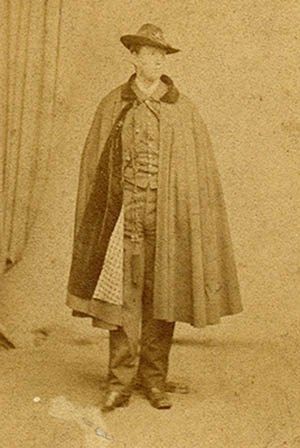

In March 1863 a seventeen year old native of Cambridge, Massachusetts, slipped away from his home on Brattle Street, hopped aboard a train and headed for Washington D.C. to join Mr. Lincoln's Army. He was by no means the first or the last youth that simply couldn't stay home while so many of his peers were off participating in the great adventure of the Civil War, but he may have been the most prominent runaway from Boston and possibly New England that year. His name was Charles Appleton Longfellow, and his father was the great poet and literary scholar, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

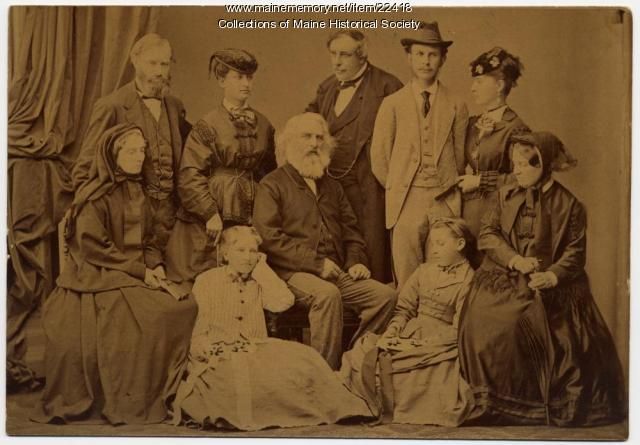

Charles Appleton Longfellow was the eldest son of HWL (as he referred to his father) and Fannie Elizabeth Appleton. He was born in Cambridge on June 9, 1844 and was raised in a loving family, which consisted, besides his parents, of three sisters and one brother. Charley was bright and adventurous and although he became a crack shot with a rifle, he managed to shoot off his left thumb with a shotgun (this eventually kept him out of the infantry when he sought to join the Union Army). His madcap adventures worried his parents and particularly his father. Mrs. Longfellow had died in a tragic fire in their home in 1860 and so Henry, as a single parent, was doubly responsible for his son who had disappeared into the great sea of blue, which was the Union Army.

Soon, however, the mystery was solved; on arrival in Washington Charley had gone to Captain W. H. McCartney, commanding Battery A of the 1st Massachusetts Artillery and asked to enlist. Captain McCartney, who knew the boy, did not want to enlist this young man without his parent's approval so he immediately wrote Henry Wadsworth Longfellow asking his advice. To his credit, or perhaps knowing his son's personality, HWL gave permission for Charley to enlist so the only member of the poet's family to go to war became a private in the 1st Massachusetts Artillery.

Charles Longfellow turned out to be a natural soldier. He grasped the elements of drill, camp, and military life with amazing aptitude. He became a great favorite with his fellow artillerymen and showed decided leadership skills, which commended him to his superior officers. In the meantime his father, thinking that his son might do better as an officer rather than a rough hewn enlisted man and began to contact friends, such as Senator Charles Sumner, Governor John Andrew and Dr. Edward B. Dalton, medical inspector of the Sixth Army Corps, with a view to obtaining a commission for his son. As he started to engage in this process of string pulling, Mr. Longfellow was surprised to hear that all his machinations were unnecessary-on his own merits Charley was offered a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, and had accepted. He was commissioned on March 27, 1863. Charley entered on his new duties with enthusiasm and was assigned to Company "G" of the 1st Massachusetts. His first action came on the fringes of the Battle of Chancellorsville. In early June Charley came down with typhoid fever and malaria and was invalided home to recover. After recuperating Charley rejoined his unit on August 15, 1863, having missed the Battle of Gettysburg. In mid-September he was in a fight at Culpepper where quartermaster sergeant Read, who was standing next to Charley had his leg taken off by artillery round. On November 27, as part of the Mine Run Campaign, while in a skirmish during the battle of New Hope Church, Virginia, Charley was shot through the left shoulder. The bullet traveled across his back, nicked his spine, and exited under his right shoulder. He missed being paralyzed by less than an inch. He was carried into the church and then by ambulance to the Rapidan River. On December 1, 1863, word was received at the Longfellow home in Cambridge of Charles serious injury. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his younger son, Ernest, left at once for Washington, D.C. where they finally met up with Charley and brought him home. They reached Cambridge on December 8 and Charles Appleton Longfellow began the slow process of recovering. As he sat nursing his son and giving thanks for his survival, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow penned the following poem:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till, ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

"There is no peace on earth," I said,

"For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men!"

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep;

God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men!

Charles Appleton Longfellow

By

Robert Girard Carroon, PCinC

Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the U.S.

23 Thompson Road

West Hartford, CT 06107

[email protected]

(October 1998)

In March 1863 a seventeen year old native of Cambridge, Massachusetts, slipped away from his home on Brattle Street, hopped aboard a train and headed for Washington D.C. to join Mr. Lincoln's Army. He was by no means the first or the last youth that simply couldn't stay home while so many of his peers were off participating in the great adventure of the Civil War, but he may have been the most prominent runaway from Boston and possibly New England that year. His name was Charles Appleton Longfellow, and his father was the great poet and literary scholar, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Charles Appleton Longfellow was the eldest son of HWL (as he referred to his father) and Fannie Elizabeth Appleton. He was born in Cambridge on June 9, 1844 and was raised in a loving family, which consisted, besides his parents, of three sisters and one brother. Charley was bright and adventurous and although he became a crack shot with a rifle, he managed to shoot off his left thumb with a shotgun (this eventually kept him out of the infantry when he sought to join the Union Army). His madcap adventures worried his parents and particularly his father. Mrs. Longfellow had died in a tragic fire in their home in 1860 and so Henry, as a single parent, was doubly responsible for his son who had disappeared into the great sea of blue, which was the Union Army.

Soon, however, the mystery was solved; on arrival in Washington Charley had gone to Captain W. H. McCartney, commanding Battery A of the 1st Massachusetts Artillery and asked to enlist. Captain McCartney, who knew the boy, did not want to enlist this young man without his parent's approval so he immediately wrote Henry Wadsworth Longfellow asking his advice. To his credit, or perhaps knowing his son's personality, HWL gave permission for Charley to enlist so the only member of the poet's family to go to war became a private in the 1st Massachusetts Artillery.

Charles Longfellow turned out to be a natural soldier. He grasped the elements of drill, camp, and military life with amazing aptitude. He became a great favorite with his fellow artillerymen and showed decided leadership skills, which commended him to his superior officers. In the meantime his father, thinking that his son might do better as an officer rather than a rough hewn enlisted man and began to contact friends, such as Senator Charles Sumner, Governor John Andrew and Dr. Edward B. Dalton, medical inspector of the Sixth Army Corps, with a view to obtaining a commission for his son. As he started to engage in this process of string pulling, Mr. Longfellow was surprised to hear that all his machinations were unnecessary-on his own merits Charley was offered a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, and had accepted. He was commissioned on March 27, 1863. Charley entered on his new duties with enthusiasm and was assigned to Company "G" of the 1st Massachusetts. His first action came on the fringes of the Battle of Chancellorsville. In early June Charley came down with typhoid fever and malaria and was invalided home to recover. After recuperating Charley rejoined his unit on August 15, 1863, having missed the Battle of Gettysburg. In mid-September he was in a fight at Culpepper where quartermaster sergeant Read, who was standing next to Charley had his leg taken off by artillery round. On November 27, as part of the Mine Run Campaign, while in a skirmish during the battle of New Hope Church, Virginia, Charley was shot through the left shoulder. The bullet traveled across his back, nicked his spine, and exited under his right shoulder. He missed being paralyzed by less than an inch. He was carried into the church and then by ambulance to the Rapidan River. On December 1, 1863, word was received at the Longfellow home in Cambridge of Charles serious injury. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his younger son, Ernest, left at once for Washington, D.C. where they finally met up with Charley and brought him home. They reached Cambridge on December 8 and Charles Appleton Longfellow began the slow process of recovering. As he sat nursing his son and giving thanks for his survival, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow penned the following poem:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till, ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

"There is no peace on earth," I said,

"For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men!"

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep;

God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men!

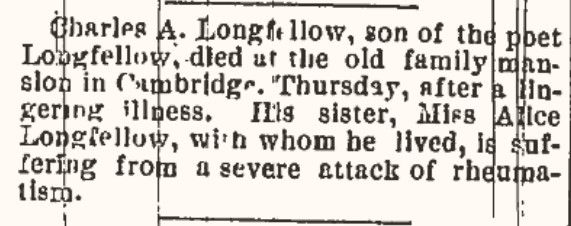

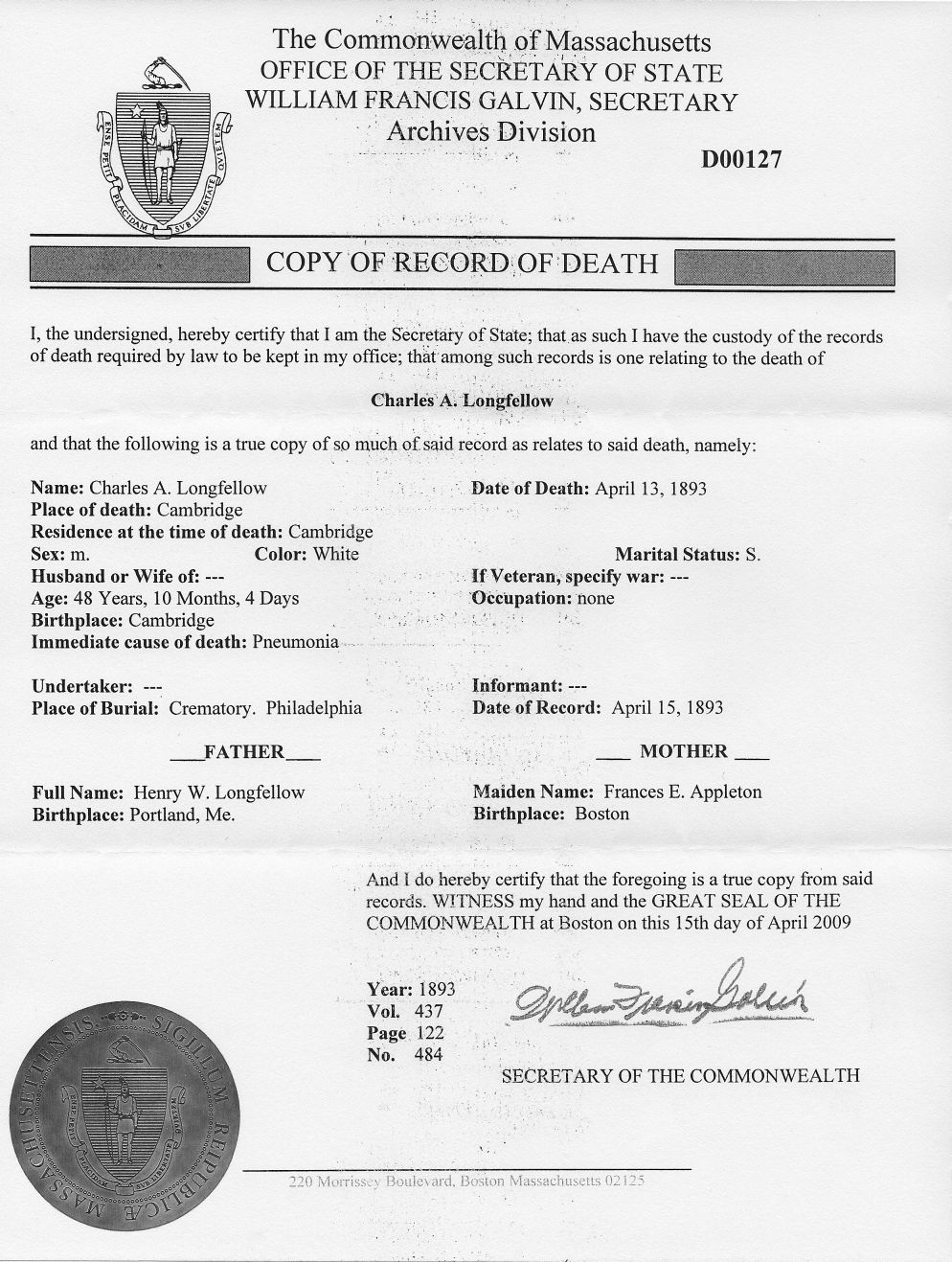

Charles Appleton Longfellow