Bowen Cemetery is located near Smiley, Texas on the old home place of Neill Bowen, known in 1878 as "Coon Hollow". Neill Bowen owned a mercantile store in Nopal, Gonzales County. The Neill Bowen home was located on "Coon Hollow", a short distance north of the store.

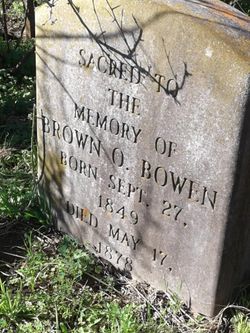

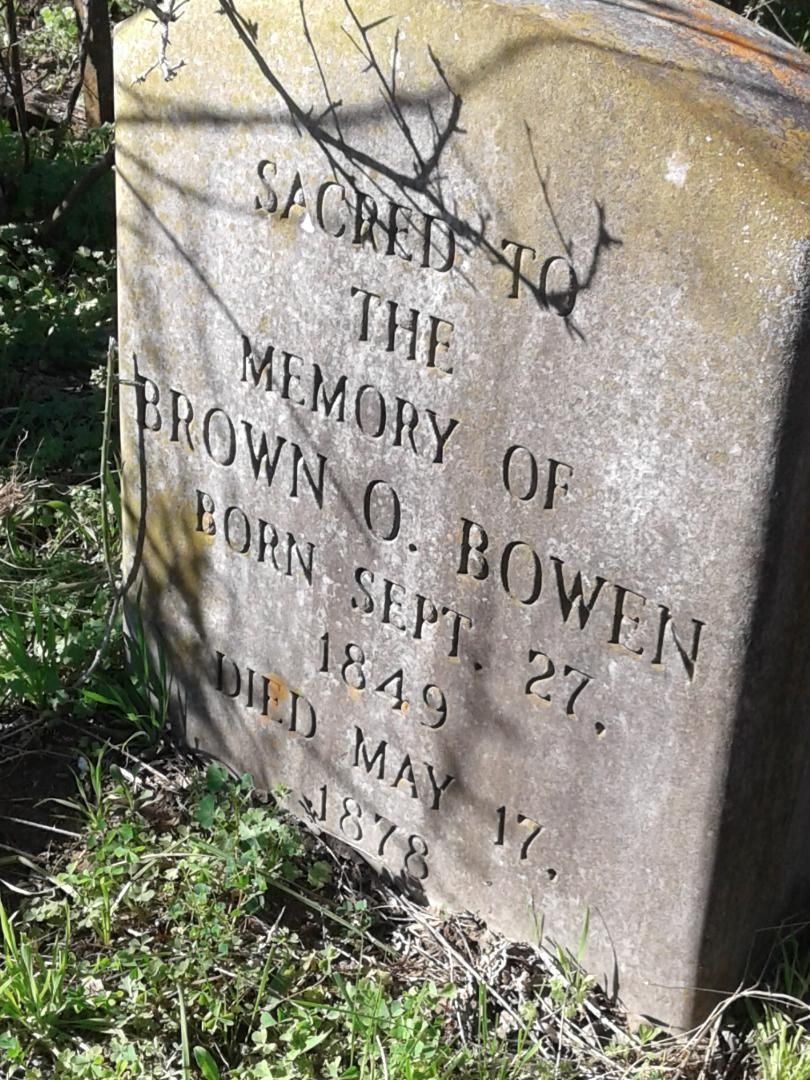

Throughout the years, the headstone for Brown Bowen was broken in many pieces. Many years ago, the fragments of the broken headstone were gathered together and placed in the Gonzales "Old Jail" Museum where they remain today. There has since been a new headstone placed for Brown Bowen, which is surrounded by an iron fence.

National Police Gazette, 1 June 1878

Bowen Bowed Out

Execution of a noted Texas desperado who tried to start a little discussion on the scaffold with the brother of the man for whose cruel murder he was justly bounced to the unknown.

(Subject of Illustration)

Gonzales, Texas, via Luling, May 17. -- For two or three weeks past, the whole country in this section has been excited about the hanging of the desperado, Brown Bowen, set for today. Amid all the hundreds of frightful murders and assassinations in this part of Texas for the last several years, there has been up to the present time but one solitary hanging. Hence, such a thing as the execution of a desperate character attracted attention and aroused popular curiosity far and near.

The great crime for which Brown Bowen was condemned to the gallows by a fair and impartial jury of his peers was about as follows: It has long been a custom in this wild, unsettled country for neighbors, and especially young men, to mount their horses and spend their leisure evenings, particularly Saturdays and Sundays, at the nearest grocery, where plenty of fire-water added zest to their revels and kindled.

The flames of animosity or of passion.

The men, young and old, of Gonzales county, especially in its more retired and rural districts, were no exceptions to the rule, and crowds of them not unfrequently collected at the grocery or in the country dram-shop to have a spree, run horse races or engage in other like amusements. Upon one occasion a crowd of this character met at a grocery store in the country. Drinking whisky was freely indulged in, and among the crowd of rollicking toughs present was John Wesley Hardin, the celebrated Texas desperado, now under sentence in Austin Jail for murder, and the history of whose exploits has been told in the columns of the GAZETTE on a former occasion. Another member of the party was a character of West Texas, little less notorious then Hardin himself - Brown Bowen, a brother-in-law of Hardin. There was another in the crowd at the grocery who had no idea death was so soon, and so suddenly to overtake him. This was Thomas Holderman. The spree was a high old Bacchanal. Corn-juice flowed very freely, and all hands without stint.

Holderman became very drunk - so drunk that he managed to navigate from the grocery only as far as a tree, under whose shade and at whose root he sank down unconscious, and resigned himself to a drunken slumber, from which he never woke. It was in evidence at the trial of the murderer that Bowen slipped up on Holderman, as the latter lay drunk and asleep, and deliberately shot him dead.

The victim never knew what killed him. There was one witness, a citizen whose testimony has never been impeached, who, unknown to the murderer, saw the deed, and upon his evidence, Bowen received sentence of death. Subsequently to his sentence, Bowen assumed the role of innocence, and in a letter to the Austin Statesman, solemnly averred before his God that he never did the killing, but his brother-in-law, John Wesley Hardin, was the murderer of Holderman. This Hardin, in a subsequent issue of the Statesman, most positively denied, saying that his load was heavy enough without being accused of crimes he had never committed, and that Bowen had not been convicted on circumstantial testimony, but the direct evidence of

An Eyewitness to the Murder

After the murder of Holderman, Brown Bowen, with his brother-in-law, John Wesley Hardin, finding Texas too hot for them, thought it prudent after a year's hunt by a Chicago detective two days before that set for Bowen's execution, Governor Hubbard examined a petition signed for the murderer's reprieve, and also listened to a touching appeal of his mother and wife. Governor Hubbard, however, refused to interfere, seeing there was no ground for clemency, it having been a most heartless and cold-blooded murder.

One of the murderer's last acts was to write the following note to his brother-in-law, John Wesley Hardin, the celebrated Texas desperado,now in jail in Austin:

"On Friday, the 17th of May, I have to pay the penalty of the law for your crime, John, you know I am innocent of this deed.

I ask you to clear my name for my children's sake. John, you know you have to appear before that Great Tribunal and look on your God and say, "I did not kill Holderman". You know you will have to say, "I, John Hardin, did it, and allowed Brown Bowen to be punished on this earth for it", which, if you do, will be another of the dreadful murders which you will have to answer for."

At 2 P.M., Bowen was hanged. The gallows was erected in public in the jail yard. --- in considering people began arriving from all directions and by two o'clock, there were five or six thousand persons present on the scene. At a little past two, Sheriff Bass appeared with the prisoner and the clergy, and closely guarded by the detachment of Texas Rangers, under command of Lieutenant Hall, with fixed bayonets. Bowen walked with a firm tread, but there was a nervous look about the face. With the sheriff at his elbow he mounted the gallows.

The murderer''s written statement of the assassination was read to the multitude, who heard it in silence and without sympathy, he declared his innocence, and thanked the clergy and Lieutenant Hall's troops. The sheriff then advanced and placed the fatal noose around the doomed man's neck. After this, Bowen seeing the brother of the murdered man in the crowd, called him up and recapitulated at some length the friendly feeling existing between himself and the murdered man, and asked the brother if this was not so. The latter assented, Bowen then asked if the latter, on the point-blank evidence, believed him (Bowen) guilty. "Yes". "Then", said Bowen, "You believe a dog-gone lie".

He declared his innocence of the crime. The black cap was removed twice - once to send a last message to his wife, declaring his innocence and urging the good training of the children; a second time to have a prayer. The platform fell amid the shudders and the low exclamations of the multitude. The murderer dropped seven feet. His neck was not broken, but after a few convulsive struggles, all was over

∼

The following info was provided by:

Donna Penton Bates

FIND A GRAVE ID 47959034

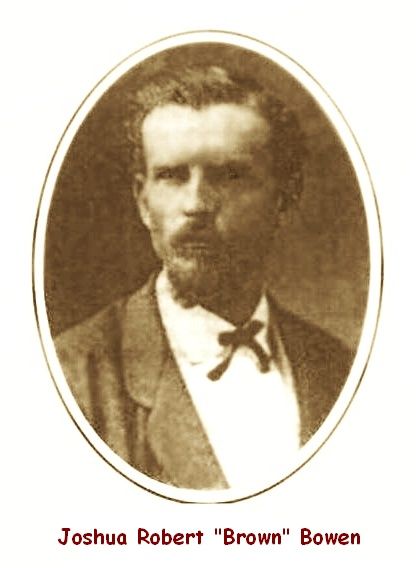

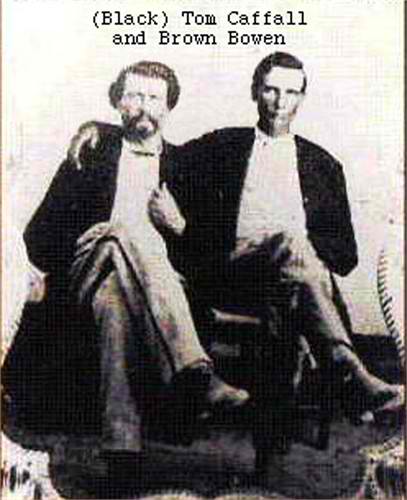

Brown hung out with his brother-in-law John Wesley Hardin. He went on cattledrives and often ran a foul of the law. He was a gunslinger also. He moved to Texas with his parents before 1868. He married first Maggie Reese in 1868 and they had a son named Thomas. In 1874, while on the run from the law for the murder of Tom Haldeman he returned to Florida where he fathered a daughter, Nora. He never married Nora's mother and in 1875 he married Mary C. Mayo and they had a son named Neil. He was captured in Florida on 17 October 1877 and returned to Texas to stand trial for Haldeman's murder. Brown denied the killing saying that John Wesley Hardin did it, but Hardin denied this also, which caused resentment between Jane (Hardin's wife) and her family. Jane stayed dedicated to John all her life. Brown was found guilty and hung in Austin, Texas on 17 May 1878 in front of a crowd of about 3000 people. His body was taken by the family to Gonzales Co. Texas and buried on the Bowen's homestead.

Bowen Cemetery is located near Smiley, Texas on the old home place of Neill Bowen, known in 1878 as "Coon Hollow". Neill Bowen owned a mercantile store in Nopal, Gonzales County. The Neill Bowen home was located on "Coon Hollow", a short distance north of the store.

Throughout the years, the headstone for Brown Bowen was broken in many pieces. Many years ago, the fragments of the broken headstone were gathered together and placed in the Gonzales "Old Jail" Museum where they remain today. There has since been a new headstone placed for Brown Bowen, which is surrounded by an iron fence.

National Police Gazette, 1 June 1878

Bowen Bowed Out

Execution of a noted Texas desperado who tried to start a little discussion on the scaffold with the brother of the man for whose cruel murder he was justly bounced to the unknown.

(Subject of Illustration)

Gonzales, Texas, via Luling, May 17. -- For two or three weeks past, the whole country in this section has been excited about the hanging of the desperado, Brown Bowen, set for today. Amid all the hundreds of frightful murders and assassinations in this part of Texas for the last several years, there has been up to the present time but one solitary hanging. Hence, such a thing as the execution of a desperate character attracted attention and aroused popular curiosity far and near.

The great crime for which Brown Bowen was condemned to the gallows by a fair and impartial jury of his peers was about as follows: It has long been a custom in this wild, unsettled country for neighbors, and especially young men, to mount their horses and spend their leisure evenings, particularly Saturdays and Sundays, at the nearest grocery, where plenty of fire-water added zest to their revels and kindled.

The flames of animosity or of passion.

The men, young and old, of Gonzales county, especially in its more retired and rural districts, were no exceptions to the rule, and crowds of them not unfrequently collected at the grocery or in the country dram-shop to have a spree, run horse races or engage in other like amusements. Upon one occasion a crowd of this character met at a grocery store in the country. Drinking whisky was freely indulged in, and among the crowd of rollicking toughs present was John Wesley Hardin, the celebrated Texas desperado, now under sentence in Austin Jail for murder, and the history of whose exploits has been told in the columns of the GAZETTE on a former occasion. Another member of the party was a character of West Texas, little less notorious then Hardin himself - Brown Bowen, a brother-in-law of Hardin. There was another in the crowd at the grocery who had no idea death was so soon, and so suddenly to overtake him. This was Thomas Holderman. The spree was a high old Bacchanal. Corn-juice flowed very freely, and all hands without stint.

Holderman became very drunk - so drunk that he managed to navigate from the grocery only as far as a tree, under whose shade and at whose root he sank down unconscious, and resigned himself to a drunken slumber, from which he never woke. It was in evidence at the trial of the murderer that Bowen slipped up on Holderman, as the latter lay drunk and asleep, and deliberately shot him dead.

The victim never knew what killed him. There was one witness, a citizen whose testimony has never been impeached, who, unknown to the murderer, saw the deed, and upon his evidence, Bowen received sentence of death. Subsequently to his sentence, Bowen assumed the role of innocence, and in a letter to the Austin Statesman, solemnly averred before his God that he never did the killing, but his brother-in-law, John Wesley Hardin, was the murderer of Holderman. This Hardin, in a subsequent issue of the Statesman, most positively denied, saying that his load was heavy enough without being accused of crimes he had never committed, and that Bowen had not been convicted on circumstantial testimony, but the direct evidence of

An Eyewitness to the Murder

After the murder of Holderman, Brown Bowen, with his brother-in-law, John Wesley Hardin, finding Texas too hot for them, thought it prudent after a year's hunt by a Chicago detective two days before that set for Bowen's execution, Governor Hubbard examined a petition signed for the murderer's reprieve, and also listened to a touching appeal of his mother and wife. Governor Hubbard, however, refused to interfere, seeing there was no ground for clemency, it having been a most heartless and cold-blooded murder.

One of the murderer's last acts was to write the following note to his brother-in-law, John Wesley Hardin, the celebrated Texas desperado,now in jail in Austin:

"On Friday, the 17th of May, I have to pay the penalty of the law for your crime, John, you know I am innocent of this deed.

I ask you to clear my name for my children's sake. John, you know you have to appear before that Great Tribunal and look on your God and say, "I did not kill Holderman". You know you will have to say, "I, John Hardin, did it, and allowed Brown Bowen to be punished on this earth for it", which, if you do, will be another of the dreadful murders which you will have to answer for."

At 2 P.M., Bowen was hanged. The gallows was erected in public in the jail yard. --- in considering people began arriving from all directions and by two o'clock, there were five or six thousand persons present on the scene. At a little past two, Sheriff Bass appeared with the prisoner and the clergy, and closely guarded by the detachment of Texas Rangers, under command of Lieutenant Hall, with fixed bayonets. Bowen walked with a firm tread, but there was a nervous look about the face. With the sheriff at his elbow he mounted the gallows.

The murderer''s written statement of the assassination was read to the multitude, who heard it in silence and without sympathy, he declared his innocence, and thanked the clergy and Lieutenant Hall's troops. The sheriff then advanced and placed the fatal noose around the doomed man's neck. After this, Bowen seeing the brother of the murdered man in the crowd, called him up and recapitulated at some length the friendly feeling existing between himself and the murdered man, and asked the brother if this was not so. The latter assented, Bowen then asked if the latter, on the point-blank evidence, believed him (Bowen) guilty. "Yes". "Then", said Bowen, "You believe a dog-gone lie".

He declared his innocence of the crime. The black cap was removed twice - once to send a last message to his wife, declaring his innocence and urging the good training of the children; a second time to have a prayer. The platform fell amid the shudders and the low exclamations of the multitude. The murderer dropped seven feet. His neck was not broken, but after a few convulsive struggles, all was over

∼

The following info was provided by:

Donna Penton Bates

FIND A GRAVE ID 47959034

Brown hung out with his brother-in-law John Wesley Hardin. He went on cattledrives and often ran a foul of the law. He was a gunslinger also. He moved to Texas with his parents before 1868. He married first Maggie Reese in 1868 and they had a son named Thomas. In 1874, while on the run from the law for the murder of Tom Haldeman he returned to Florida where he fathered a daughter, Nora. He never married Nora's mother and in 1875 he married Mary C. Mayo and they had a son named Neil. He was captured in Florida on 17 October 1877 and returned to Texas to stand trial for Haldeman's murder. Brown denied the killing saying that John Wesley Hardin did it, but Hardin denied this also, which caused resentment between Jane (Hardin's wife) and her family. Jane stayed dedicated to John all her life. Brown was found guilty and hung in Austin, Texas on 17 May 1878 in front of a crowd of about 3000 people. His body was taken by the family to Gonzales Co. Texas and buried on the Bowen's homestead.

Inscription

Sacred to the Memory of Brown Bowen

Family Members

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement