BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY

Vanderlip, Frank Arthur (Nov. 17, 1864 - June 29, 1937), editor, banker, and government official, was born on a farm near Aurora, Ill., the first son and second of three children of Charles and Charlotte (Woodworth) Vanderlip. His father, a descendant of William Vanderlip who came to America from Holland in 1756 and settled in Pennsylvania, was born in Ohio, drifted to Illinois, and learned the blacksmith's trade. His mother's ancestors had moved west from Salem, Mass., by way of South Lee, Mass., and Cleveland, Ohio; her family owned a wagon shop. When Frank was barely thirteen his father and younger brother died of tuberculosis. Economic reverses led to the forced sale of the family farm, and Frank became responsible for the support of a household which included, in addition to his mother and sister, a grandmother and two maiden aunts. Leaving school, he went to work in an Aurora machine shop, where he learned to operate a lathe; but he read widely, was tutored in drafting, mathematics, and German, studied shorthand at night, and also worked his way through a year's course in mechanical engineering at the University of Illinois.

He left the machine shop in 1885 to become city editor of the Aurora Evening Post. Here he made a friendship which importantly affected his career. His fellow townsman Joseph French Johnson [q.v.], then head of a financial investigating agency in Chicago, secured him a position in the agency, where he began a fruitful study of railroad and other financial reports. In 1889 Johnson, then a staff member of the Chicago Tribune, got Vanderlip a post as financial reporter on that paper, where he quickly rose to be financial editor. In 1894 he became associate editor of The Economist, a Chicago weekly publication. Meanwhile he had completed a year's course in economics and finance at the newly established University of Chicago. Already a respected authority, he was called upon to lecture on finance at a number of midwestern colleges and universities.

Vanderlip's reputation in Chicago led to his appointment on Mar. 4, 1897, as private secretary to Lyman J. Gage [q.v.], the Chicago banker whom President McKinley had appointed Secretary of the Treasury. After three months Vanderlip became Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, gaining a national reputation for his part in floating the $200,000,000 Spanish War loan of 1898. In 1901 he joined the National City Bank of New York as a vice-president. With the close support of James Stillman [q.v.], president of the bank, Vanderlip introduced a whole series of innovations--soliciting new accounts, entering into the investment field, developing foreign and domestic branch-banking, and initiating a monthly "bank letter" that became famous all over the world. When Stillman retired to become chairman of the board in 1909, Vanderlip succeeded him as president and served in that capacity for ten years. Among his innovations was the organized training of selected college graduates as future bank officers. By the end of his administration the National City Bank had become the largest in the United States and had greatly increased its activities abroad.

This foreign expansion reflected one of Vanderlip's main interests. Before taking up his duties in 1901 he had made an extended trip through Europe studying public and private financial policies. In subsequent years he repeated these "studies on the spot," becoming a leading American authority on foreign finance. Under his leadership the National City Bank established branches in strategic financial centers in Europe (including Russia), in Latin America, and, through the acquisition of a controlling interest in the International Banking Corporation, in the Far East, and did much to stimulate the interest of American bankers generally in foreign trade and international banking.

During World War I Vanderlip took a leave of absence from the bank to serve the Treasury Department as chairman of the War Savings Committee. After the war he traveled in Europe. On his return, finding the atmosphere at the bank less congenial since Stillman's death (1918), he sold his City Bank stock and, in 1919, resigned as president.

Thereafter, while engaging in various private ventures, Vanderlip maintained his interest in public affairs. He actively opposed the growing trend toward isolationism in American foreign policy. He spoke out against the scandals in the Harding administration (a stand which cost him a number of corporation directorships) and organized and directed the Citizens' Federal Research Bureau to assist in investigating them. In the 1924 campaign he opposed Coolidge and helped to induce Burton K. Wheeler to accept the vice-presidential nomination on the Progressive ticket. For decades he had been interested in banking reform, and he had shared in the preparation of the "Aldrich Plan" at a secret bankers' meeting called by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich [q.v.] on Jekyl Island, Ga. (1910). In 1933, as chairman of the Committee for the Nation, he advocated abandonment of the gold standard and devaluation of the dollar. He also took an active part in the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, helping to draw up its original plans in 1905 and serving for the rest of his life as trustee.

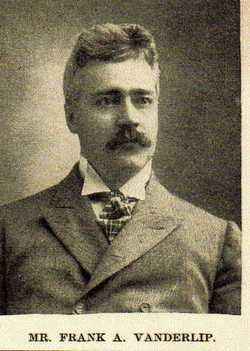

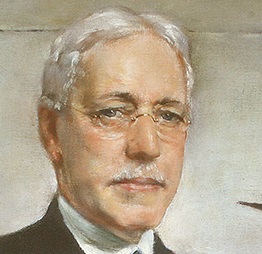

Physically Vanderlip was of medium build and, with glasses and a close-trimmed mustache, made an impressive appearance. He was generous and kindly in disposition but reserved in manner. In his autobiography he laments that he never learned to play. Although he organized the Sleepy Hollow Country Club, directed the laying out of its links, and was for years its president, he never took up golf. He learned to smoke after he was forty, but he never drank. In his social relations with other bankers he considered himself a "wet blanket," and once lamented that "almost no one calls me Frank."

He was thirty-eight before romance entered his life. In the spring of 1903 he married Narcissa Cox, a college friend of his sister. Six children were born to them: Narcissa, Charlotte Delight, Frank Arthur, Virginia Jocelyn, Kelvin Cox, and John Mann. The family lived at "Beechwood," a 125-acre estate at Scarborough-on-the-Hudson, where Vanderlip, with his wife's help, established and endowed the Scarborough School. He died in New York City, a victim of intestinal complications and diabetes. Interment of the cremated remains was in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Tarrytown, N. Y.

-- Eugene E. Agger

FURTHER READINGS

[Vanderlip was a frequent public speaker and contributor to newspapers and magazines; the best of his essays and addresses were collected under the title Business and Education (1907). Two books reflect his interest in international affairs: What Happened to Europe (1919) and What Next in Europe (1922). He also wrote Tomorrow's Money (1934) and an autobiog., From Farm Boy to Financier (1935), which carries his story to his retirement as bank president. See also Who's Who in America, 1934-35; article on Vanderlip in B. C. Forbes, Men Who Are Making America (1917); Nat. Cyc. Am. Biog., XV, 29; N. Y. Times, N. Y. Herald Tribune, June 30, 1937.]

BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY

Vanderlip, Frank Arthur (Nov. 17, 1864 - June 29, 1937), editor, banker, and government official, was born on a farm near Aurora, Ill., the first son and second of three children of Charles and Charlotte (Woodworth) Vanderlip. His father, a descendant of William Vanderlip who came to America from Holland in 1756 and settled in Pennsylvania, was born in Ohio, drifted to Illinois, and learned the blacksmith's trade. His mother's ancestors had moved west from Salem, Mass., by way of South Lee, Mass., and Cleveland, Ohio; her family owned a wagon shop. When Frank was barely thirteen his father and younger brother died of tuberculosis. Economic reverses led to the forced sale of the family farm, and Frank became responsible for the support of a household which included, in addition to his mother and sister, a grandmother and two maiden aunts. Leaving school, he went to work in an Aurora machine shop, where he learned to operate a lathe; but he read widely, was tutored in drafting, mathematics, and German, studied shorthand at night, and also worked his way through a year's course in mechanical engineering at the University of Illinois.

He left the machine shop in 1885 to become city editor of the Aurora Evening Post. Here he made a friendship which importantly affected his career. His fellow townsman Joseph French Johnson [q.v.], then head of a financial investigating agency in Chicago, secured him a position in the agency, where he began a fruitful study of railroad and other financial reports. In 1889 Johnson, then a staff member of the Chicago Tribune, got Vanderlip a post as financial reporter on that paper, where he quickly rose to be financial editor. In 1894 he became associate editor of The Economist, a Chicago weekly publication. Meanwhile he had completed a year's course in economics and finance at the newly established University of Chicago. Already a respected authority, he was called upon to lecture on finance at a number of midwestern colleges and universities.

Vanderlip's reputation in Chicago led to his appointment on Mar. 4, 1897, as private secretary to Lyman J. Gage [q.v.], the Chicago banker whom President McKinley had appointed Secretary of the Treasury. After three months Vanderlip became Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, gaining a national reputation for his part in floating the $200,000,000 Spanish War loan of 1898. In 1901 he joined the National City Bank of New York as a vice-president. With the close support of James Stillman [q.v.], president of the bank, Vanderlip introduced a whole series of innovations--soliciting new accounts, entering into the investment field, developing foreign and domestic branch-banking, and initiating a monthly "bank letter" that became famous all over the world. When Stillman retired to become chairman of the board in 1909, Vanderlip succeeded him as president and served in that capacity for ten years. Among his innovations was the organized training of selected college graduates as future bank officers. By the end of his administration the National City Bank had become the largest in the United States and had greatly increased its activities abroad.

This foreign expansion reflected one of Vanderlip's main interests. Before taking up his duties in 1901 he had made an extended trip through Europe studying public and private financial policies. In subsequent years he repeated these "studies on the spot," becoming a leading American authority on foreign finance. Under his leadership the National City Bank established branches in strategic financial centers in Europe (including Russia), in Latin America, and, through the acquisition of a controlling interest in the International Banking Corporation, in the Far East, and did much to stimulate the interest of American bankers generally in foreign trade and international banking.

During World War I Vanderlip took a leave of absence from the bank to serve the Treasury Department as chairman of the War Savings Committee. After the war he traveled in Europe. On his return, finding the atmosphere at the bank less congenial since Stillman's death (1918), he sold his City Bank stock and, in 1919, resigned as president.

Thereafter, while engaging in various private ventures, Vanderlip maintained his interest in public affairs. He actively opposed the growing trend toward isolationism in American foreign policy. He spoke out against the scandals in the Harding administration (a stand which cost him a number of corporation directorships) and organized and directed the Citizens' Federal Research Bureau to assist in investigating them. In the 1924 campaign he opposed Coolidge and helped to induce Burton K. Wheeler to accept the vice-presidential nomination on the Progressive ticket. For decades he had been interested in banking reform, and he had shared in the preparation of the "Aldrich Plan" at a secret bankers' meeting called by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich [q.v.] on Jekyl Island, Ga. (1910). In 1933, as chairman of the Committee for the Nation, he advocated abandonment of the gold standard and devaluation of the dollar. He also took an active part in the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, helping to draw up its original plans in 1905 and serving for the rest of his life as trustee.

Physically Vanderlip was of medium build and, with glasses and a close-trimmed mustache, made an impressive appearance. He was generous and kindly in disposition but reserved in manner. In his autobiography he laments that he never learned to play. Although he organized the Sleepy Hollow Country Club, directed the laying out of its links, and was for years its president, he never took up golf. He learned to smoke after he was forty, but he never drank. In his social relations with other bankers he considered himself a "wet blanket," and once lamented that "almost no one calls me Frank."

He was thirty-eight before romance entered his life. In the spring of 1903 he married Narcissa Cox, a college friend of his sister. Six children were born to them: Narcissa, Charlotte Delight, Frank Arthur, Virginia Jocelyn, Kelvin Cox, and John Mann. The family lived at "Beechwood," a 125-acre estate at Scarborough-on-the-Hudson, where Vanderlip, with his wife's help, established and endowed the Scarborough School. He died in New York City, a victim of intestinal complications and diabetes. Interment of the cremated remains was in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Tarrytown, N. Y.

-- Eugene E. Agger

FURTHER READINGS

[Vanderlip was a frequent public speaker and contributor to newspapers and magazines; the best of his essays and addresses were collected under the title Business and Education (1907). Two books reflect his interest in international affairs: What Happened to Europe (1919) and What Next in Europe (1922). He also wrote Tomorrow's Money (1934) and an autobiog., From Farm Boy to Financier (1935), which carries his story to his retirement as bank president. See also Who's Who in America, 1934-35; article on Vanderlip in B. C. Forbes, Men Who Are Making America (1917); Nat. Cyc. Am. Biog., XV, 29; N. Y. Times, N. Y. Herald Tribune, June 30, 1937.]

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement