Whaley and The Textile Industry in Columbia:

Olympia Mill Village is situated just south of downtown Columbia, immediately outside the city limits. South Carolina's capital city sits on the eastern side of the confluence of the Saluda and Broad Rivers, which together form the Congaree River. The city is nearly in the center of the state and was officially established as the seat of state government following the American Revolution, although the area had been settled since the mid-1700s. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, Columbia's population grew as state government and commerce expanded. Following the Civil War,Columbia, like other southern cities and the rest of South Carolina, faced a period of slow recovery and adjustment as the region moved towards a New South economy fueled by railroads and industrialization.

The concept of a New South developed after the Civil War and reached its height in the 1890s and 1910s. The New South aimed at making the region less dependent on agriculture through economic progress, civic duty, and social changes. The movement's leaders wanted, in effect, to make the South more like the North. The main component in the creation of this reinvented region, particularly in the Piedmont regions of North and South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama, was the textile mill. In South Carolina, textile production dates from the mid-eighteenth century when yarn and cloth were produced in private homes and in small factories for very limited local consumption. Antebellum industrial pursuits were conducted only on a small scale and most antebellum South Carolinians grew cotton or produced other raw materials that would be manufactured

elsewhere.

There were, however, a few exceptions. One in particular was William Gregg who, in 1847, set up a large textile plant in South Carolina. Called the Graniteville

Manufacturing Company, the factory was equipped with 9,245 spindles and 300 looms, making it the largest antebellum textile factory in the South, and one of the region's largest industrial plants. Like New England manufacturers, Gregg established Graniteville in a rural area where he could take advantage of waterpower, and provided housing, stores, hotels, churches, and schools for workers and their families because the mill stood isolated from community services. By following the New England pattern, Gregg helped establish the method of mill development that the South followed fifty years later when it transformed itself into the post-Civil War, industrialized, New South.

Thirteen years after Gregg founded his company, only eighteen cotton mills operated in South Carolina. These factories housed 26,000 spindles and employed 891

people. By comparison, Massachusetts' 271 mills had over one and a half million spindles and employed 38,451 operatives. The textile industry's slow growth ceased altogether with the outbreak of the Civil War.

In February 1865, Union troops, apparently under the influence of alcohol rather than Sherman's command, set much of Columbia ablaze, destroying the business district, homes, and the old State House. The new capitol, still under construction, was damaged and railroad tracks were torn up. Although not completely devastated, Columbia was left battered and bruised.

When the war ended, railroad companies repaired tracks and built new rail lines, and by the turn of the twentieth century, Columbia functioned as a regional rail hub with eleven separate rail lines bringing 144 trains to the city daily. Simultaneously, advances were being made in the creation and use of electricity while New South entrepreneurs were sounding the cry, "Bring the mills to the cotton." South Carolina and Columbia were key participants in the New South movement and in textile mill development.

With the New South focus on civic responsibility and industrialization, South Carolina's business leaders worked to instill community pride through the use of slogans and expositions. Spartanburg tried several slogans, among them, "The City of Smokestacks and Education." Greenville became the "Pearl of the Piedmont." In 1901 and 1902, Charleston sponsored the less-than-successful South Carolina Interstate and West Indian Exposition, while in true New South fashion, Greenville hosted the wildly successful Southern Textile Exposition.

By the late nineteenth century, steam power and electricity eliminated the necessity of locating mills near strong rivers, and thus, with the mill free from the constraints of waterpower, the desirability of providing worker housing faded in New England. In the South, too, manufacturers had flexibility when choosing the location of their mills, but they continued to use rural locations where mill villages were necessary. The mill village allowed manufacturers to exercise paternalistic control over their workers and lure workers with the provision of housing.

One of the leaders in the New South movement was Charlotte's D.A. Tompkins, whose widely disseminated recommendations directed that a 10,000-spindle mill should have five to ten acres for the mill site, and about forty acres for houses, providing each house with room for a garden. He advised mill investors to build "a factory one to four miles away from a city and let the company build and own the houses the employees live in." This strategy avoided local property taxes, local governmental jurisdiction, and allowed mill owners to maintain social and economic control over their workers. Tompkins also noted that in a remote location, with no existing stores, "the benefit of mercantile features may be enjoyed by the mill company." Furthermore, lawyers who may attempt to interfere with the mill's operations or sue over injuries that operatives may sustain would also be kept at bay. Tompkins believed downtown living would corrupt workers, as would indoor plumbing or housing more spacious than one room per operative and at the end of the day, employees in a rural setting would be more apt to go to bed early, and therefore would be in better condition to work during the day.

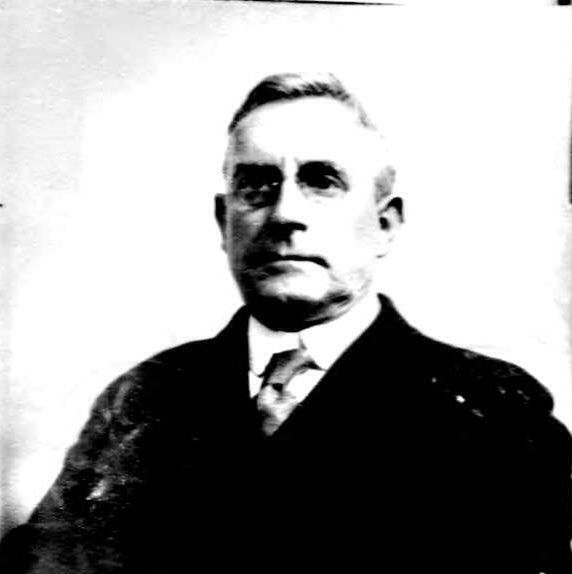

Across the South, cotton mills were constructed at explosive rates. Fourteen mills stood in South Carolina in 1880, even fewer than in 1860. But between 1895 and 1907, sixty-one new textile mills were built and older ones were expanded and updated. By 1910, there were 167 cotton mills in South Carolina, a number second only to Massachusetts. A key group of South Carolina mill developers were responsible for much of this boom. These barons included Leroy Springs, John T. Woodside, and Lewis W. Parker whose company eventually operated more than one million spindles in South Carolina. Charleston native W.B. Smith Whaley, however, was South Carolina's main proponent of textile production and innovator in mill design.

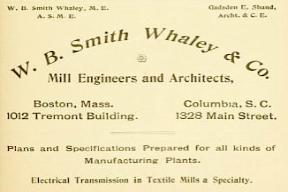

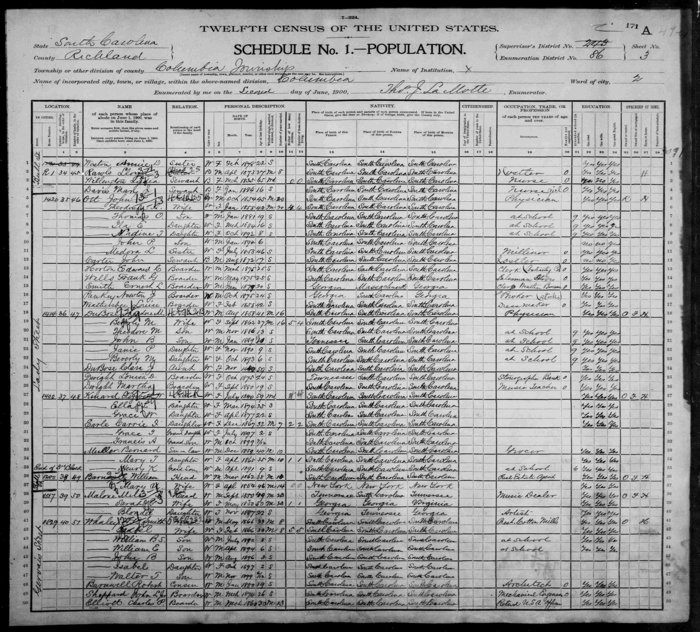

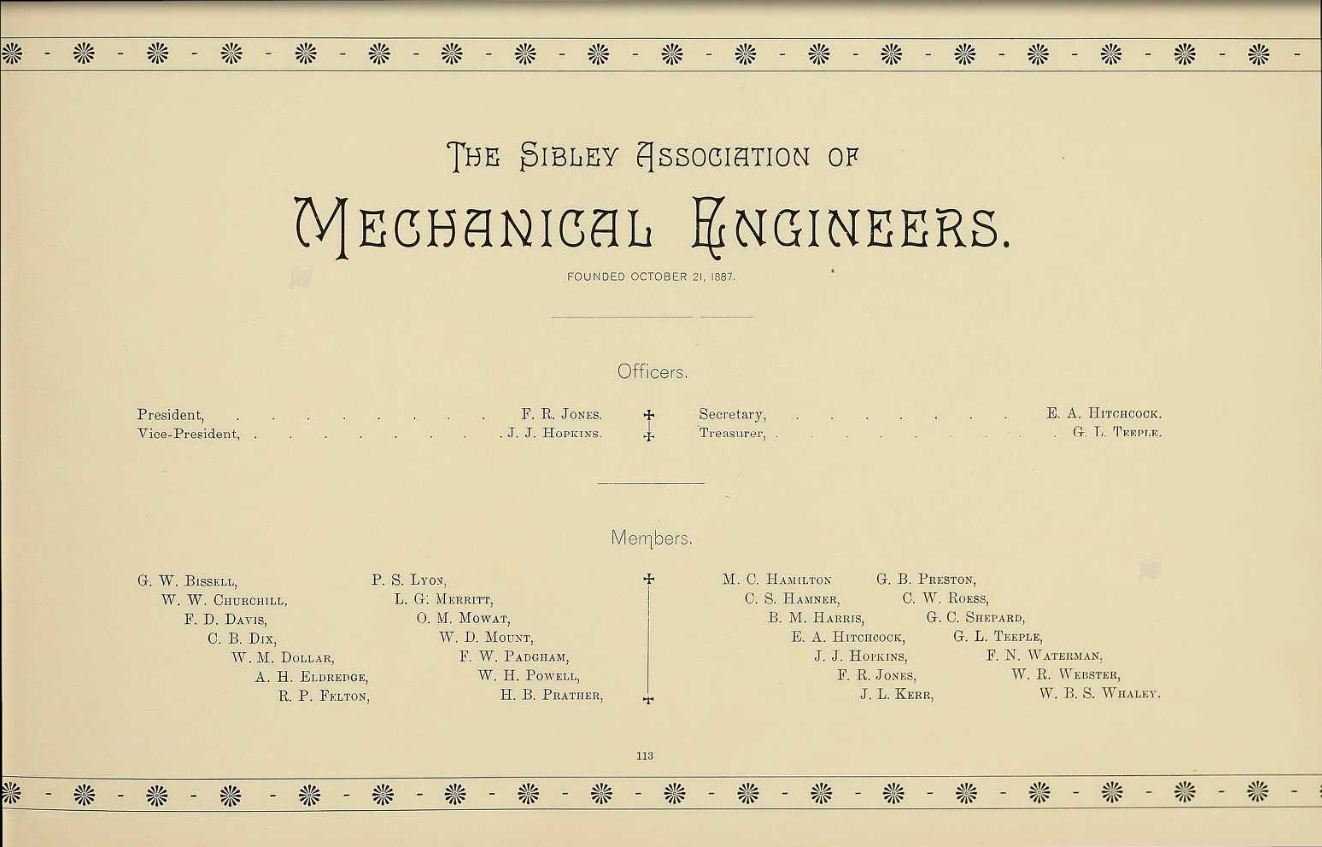

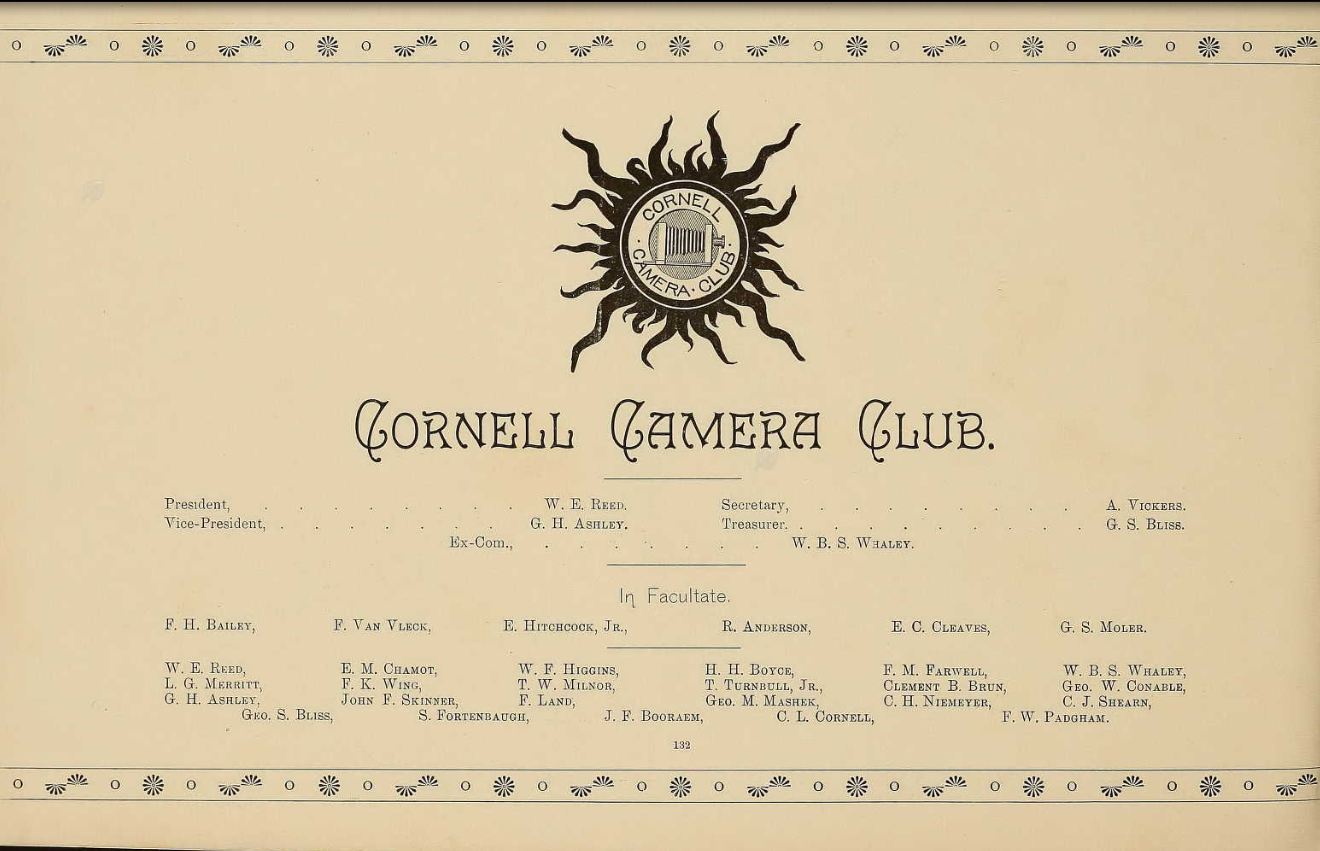

Whaley, like many of his New South counterparts, received much of his education in the North, attending Stevens Institute of Technology and Cornell University, from which he graduated in 1888. After working as a mechanical engineer in Rhode Island and being exposed to textile mill design and operation, Whaley returned to South Carolina in 1893, establishing himself in Columbia as a mechanical engineer specializing in mill design. The following year, Whaley and Gadsden E. Shand, a Columbia civil engineer, founded W.B. Smith Whaley and Company. Between 1895 and 1907, the firm designed twenty-one mills in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and North Carolina, most of them in South Carolina. One of his largest mills was the sixty thousand-spindle F.W. Poe Manufacturing Company in Greenville with over nine hundred employees. Through the firm's work, Whaley and Company introduced many architectural and technological innovations to mill design in South Carolina.

Columbia's mill development, both in and near the city, mirrors the history of textile manufacturing across the Carolinas. From a slow antebellum start, textiles evolved

as the major economic engine in the city by the early twentieth century. Small textile concerns operated in and around Columbia from its earliest days. The first substantial factory was the Saluda Manufacturing Company, chartered in 1834 and located about two miles north of Columbia. The company operated off and on for about fifty years, but it was never a success and burned in 1884. The arrival of the railroad and improved energy sources were necessary for modern textile production, but once those two needs were met, the scene was set for the arrival of the modern manufacturing. Although New South industrialists like D.A. Tompkins recommended that mills be built along railroads in rural areas, the allure of Columbia's extensive rail connections and readily accessible electricity pulled manufacturing facilities towards the capital. As in Charlotte, several mills were located on the edge of the city or just beyond the city limits, but despite

neighboring urbanity, mill villages were still constructed, lending credence to the notion of the mill owner's desire for control of his operatives.

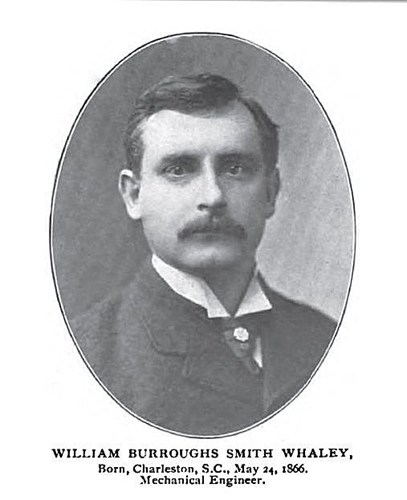

By 1920, an estimated one-sixth of the state's white population lived in mill villages. Columbia's first post-Civil War mill was the Congaree Manufacturing Company, a small, steam-powered operation that proved unsuccessful and lasted only about three years. Three other mills began operating around the turn of the twentieth century. Founded in 1894, Columbia Mills Company was the first mill in the United States to be powered entirely with electricity. The Palmetto Cotton Mills opened in 1899 and the Glencoe Cotton Mill began operations in 1909. Four other Columbia mills date from the textile boom-period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: Richland Cotton Mills Company (1895), Granby Cotton Mills Company (1897), Olympia Cotton Mills (1899), and the Capital City Mills (1900). Although the Richland Mill was a steam-powered facility, the other mills took advantage of the electricity produced at the recently completed hydroelectric plant on the Columbia Canal. Whaley and Company designed and managed these mills, collectively known as the Whaley Mills, and they represent the firm's most advanced and innovative designs.

The Whaley Mills, on the city's southern edge and easily visible from the State House, brought the New South economy to the capital as well as the poverty associated with mill villages. Workers labored from six in the morning to 6:30 p.m. Monday through Friday and for nine hours on Saturday for wages that were, on average, sixty-percent lower than those earned by mill hands in other parts of the country. An 1896 "Christmas tree" benefit for impoverished children sponsored by The State, had to be postponed from its Christmas Eve date to December twenty-sixth when it was discovered that most of the beneficiaries would be working at the mills on Christmas Eve, but would have a half day off on Saturday, the twenty-sixth. By the following year, the Columbia Ladies' Benevolent Society was one of many local charities becoming overwhelmed by requests for assistance and appealing to the public for more help: "Since the establishment of more factories, there is a greater number of cases calling for relief, and the illness of the past summer among this class, as well as among others, having depleted our treasury, we ask contributions from the generous hearted, whose sympathies abound for the poor."

In 1907, when August Kohn wrote The Cotton Mills of South Carolina, two thousand thirty-six people worked in the four Whaley Mills. Of those, officials reported to Kohn that only thirty-two were under the age of twelve, but Kohn notes, "every mill did not freely give the desired data." Kohn reported that of the three hundred fifty children living in the Olympia mill village, only one hundred and forty attended school. This was despite the fact that a 1903 South Carolina law directed that no child under ten could be employed in a factory, mine, or mill. The age increased to eleven in 1904 and to twelve in 1905.

Mill owners and operators maintained control of the low-paid operatives and minimized complaints about hours, wages, and working conditions through well-applied paternalism. By providing housing that was often better than that the operatives had left behind in the country, schools, churches, recreational, and health facilities, owners convinced both workers and the public that the company was taking care of its own. In reality, however, schools were poorly run and were often over-crowded or under-attended, housing was sometimes sub-standard, churches were "designed less for the encouragement of religion than for its control," and the company maintained price controls at the store, often assisting in the operative's descent into debt. Like the mill's bell or whistle wafting into the mill house dictating the beginning and end of every shift, the company had access to every aspect of the operative's life.

Broadus Mitchell, in his 1930 book, The Industrial Revolution in the South, wrote, "The church and the school, not to speak of the welfare departments, have been sponsored and contributed to by the employers, and have been engines of his will and servers of his convenience." He went on to say that operatives have been "stall fed," receiving "a considerable part of their compensation in kind – gardens, medical attention, free pasturage, wood and coal at cost, and, above all, exceedingly low rents." In this situation, workers were bound to the mill because they had little cash and operatives generally accepted the services of the mill in exchange for their silence about unsafe working environments and unsanitary living conditions. Mitchell acknowledged that textile mills provided employment to a segment of the rural population (poor, landless whites) that was often living in abject poverty, but he felt that "the company-owned mill village has some time since become a means of repression of the worker, consciously maintained by the employer."

Mitchell was not the only writer discussing the paternalism of the textile mill.

Paul Blanshard, writing for the New Republic in 1927, reported, "What the mill workers gain in well repaired roofs and inside toilets, they lose in community control....The worker has neither standing as a citizen nor training for citizenship apart from the dominant figure of his industrial overlord." Indicating that the services provided by the company stifled reform, he wrote, "Social workers hired by kindly mill owners give excellent personal service, but they are not free to criticize the worst features of village life." By providing housing and other assistance to operatives, mill management hoped to stay beyond reproach in the eyes of the workers and the public. In Columbia, where since 1891 Labor Day had been celebrated with unusual gusto, labor unrest arrived early.

The National Union of Textile Workers participated in the 1900 Labor Day parade and began a call for child labor legislation, the establishment of a state bureau of labor with inspection powers, and reduced working hours. Although The State reported, "Labor organizations have cut no figure here. The people are satisfied with a good living and want no disturbance of the amicable relations between capital and themselves," the management of the Whaley Mills nervously announced plans to build a public hall, library, and school and donate land and money towards the construction of a

church. This did not pacify workers and by August 1901, with many of his workers planning to march in the Labor Day parade, Whaley ordered operatives to work overtime to make up their lost hours in advance of the parade. When the mill hands failed to work overtime on Saturday, they found themselves locked out on Monday morning. On August 28, mill employees went on strike, but the mills continued to run and strikers were given eviction notices. Whaley, however, did not like The State's coverage of the strike. He denounced the press, and thus lost a potentially valuable ally. Ultimately, with the union unable to offer meaningful financial assistance to the strikers, the strike fizzled and just four months later, workers presented Whaley with a gold watch for Christmas.

************************************************************

Whaley and The Textile Industry in Columbia:

Olympia Mill Village is situated just south of downtown Columbia, immediately outside the city limits. South Carolina's capital city sits on the eastern side of the confluence of the Saluda and Broad Rivers, which together form the Congaree River. The city is nearly in the center of the state and was officially established as the seat of state government following the American Revolution, although the area had been settled since the mid-1700s. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, Columbia's population grew as state government and commerce expanded. Following the Civil War,Columbia, like other southern cities and the rest of South Carolina, faced a period of slow recovery and adjustment as the region moved towards a New South economy fueled by railroads and industrialization.

The concept of a New South developed after the Civil War and reached its height in the 1890s and 1910s. The New South aimed at making the region less dependent on agriculture through economic progress, civic duty, and social changes. The movement's leaders wanted, in effect, to make the South more like the North. The main component in the creation of this reinvented region, particularly in the Piedmont regions of North and South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama, was the textile mill. In South Carolina, textile production dates from the mid-eighteenth century when yarn and cloth were produced in private homes and in small factories for very limited local consumption. Antebellum industrial pursuits were conducted only on a small scale and most antebellum South Carolinians grew cotton or produced other raw materials that would be manufactured

elsewhere.

There were, however, a few exceptions. One in particular was William Gregg who, in 1847, set up a large textile plant in South Carolina. Called the Graniteville

Manufacturing Company, the factory was equipped with 9,245 spindles and 300 looms, making it the largest antebellum textile factory in the South, and one of the region's largest industrial plants. Like New England manufacturers, Gregg established Graniteville in a rural area where he could take advantage of waterpower, and provided housing, stores, hotels, churches, and schools for workers and their families because the mill stood isolated from community services. By following the New England pattern, Gregg helped establish the method of mill development that the South followed fifty years later when it transformed itself into the post-Civil War, industrialized, New South.

Thirteen years after Gregg founded his company, only eighteen cotton mills operated in South Carolina. These factories housed 26,000 spindles and employed 891

people. By comparison, Massachusetts' 271 mills had over one and a half million spindles and employed 38,451 operatives. The textile industry's slow growth ceased altogether with the outbreak of the Civil War.

In February 1865, Union troops, apparently under the influence of alcohol rather than Sherman's command, set much of Columbia ablaze, destroying the business district, homes, and the old State House. The new capitol, still under construction, was damaged and railroad tracks were torn up. Although not completely devastated, Columbia was left battered and bruised.

When the war ended, railroad companies repaired tracks and built new rail lines, and by the turn of the twentieth century, Columbia functioned as a regional rail hub with eleven separate rail lines bringing 144 trains to the city daily. Simultaneously, advances were being made in the creation and use of electricity while New South entrepreneurs were sounding the cry, "Bring the mills to the cotton." South Carolina and Columbia were key participants in the New South movement and in textile mill development.

With the New South focus on civic responsibility and industrialization, South Carolina's business leaders worked to instill community pride through the use of slogans and expositions. Spartanburg tried several slogans, among them, "The City of Smokestacks and Education." Greenville became the "Pearl of the Piedmont." In 1901 and 1902, Charleston sponsored the less-than-successful South Carolina Interstate and West Indian Exposition, while in true New South fashion, Greenville hosted the wildly successful Southern Textile Exposition.

By the late nineteenth century, steam power and electricity eliminated the necessity of locating mills near strong rivers, and thus, with the mill free from the constraints of waterpower, the desirability of providing worker housing faded in New England. In the South, too, manufacturers had flexibility when choosing the location of their mills, but they continued to use rural locations where mill villages were necessary. The mill village allowed manufacturers to exercise paternalistic control over their workers and lure workers with the provision of housing.

One of the leaders in the New South movement was Charlotte's D.A. Tompkins, whose widely disseminated recommendations directed that a 10,000-spindle mill should have five to ten acres for the mill site, and about forty acres for houses, providing each house with room for a garden. He advised mill investors to build "a factory one to four miles away from a city and let the company build and own the houses the employees live in." This strategy avoided local property taxes, local governmental jurisdiction, and allowed mill owners to maintain social and economic control over their workers. Tompkins also noted that in a remote location, with no existing stores, "the benefit of mercantile features may be enjoyed by the mill company." Furthermore, lawyers who may attempt to interfere with the mill's operations or sue over injuries that operatives may sustain would also be kept at bay. Tompkins believed downtown living would corrupt workers, as would indoor plumbing or housing more spacious than one room per operative and at the end of the day, employees in a rural setting would be more apt to go to bed early, and therefore would be in better condition to work during the day.

Across the South, cotton mills were constructed at explosive rates. Fourteen mills stood in South Carolina in 1880, even fewer than in 1860. But between 1895 and 1907, sixty-one new textile mills were built and older ones were expanded and updated. By 1910, there were 167 cotton mills in South Carolina, a number second only to Massachusetts. A key group of South Carolina mill developers were responsible for much of this boom. These barons included Leroy Springs, John T. Woodside, and Lewis W. Parker whose company eventually operated more than one million spindles in South Carolina. Charleston native W.B. Smith Whaley, however, was South Carolina's main proponent of textile production and innovator in mill design.

Whaley, like many of his New South counterparts, received much of his education in the North, attending Stevens Institute of Technology and Cornell University, from which he graduated in 1888. After working as a mechanical engineer in Rhode Island and being exposed to textile mill design and operation, Whaley returned to South Carolina in 1893, establishing himself in Columbia as a mechanical engineer specializing in mill design. The following year, Whaley and Gadsden E. Shand, a Columbia civil engineer, founded W.B. Smith Whaley and Company. Between 1895 and 1907, the firm designed twenty-one mills in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and North Carolina, most of them in South Carolina. One of his largest mills was the sixty thousand-spindle F.W. Poe Manufacturing Company in Greenville with over nine hundred employees. Through the firm's work, Whaley and Company introduced many architectural and technological innovations to mill design in South Carolina.

Columbia's mill development, both in and near the city, mirrors the history of textile manufacturing across the Carolinas. From a slow antebellum start, textiles evolved

as the major economic engine in the city by the early twentieth century. Small textile concerns operated in and around Columbia from its earliest days. The first substantial factory was the Saluda Manufacturing Company, chartered in 1834 and located about two miles north of Columbia. The company operated off and on for about fifty years, but it was never a success and burned in 1884. The arrival of the railroad and improved energy sources were necessary for modern textile production, but once those two needs were met, the scene was set for the arrival of the modern manufacturing. Although New South industrialists like D.A. Tompkins recommended that mills be built along railroads in rural areas, the allure of Columbia's extensive rail connections and readily accessible electricity pulled manufacturing facilities towards the capital. As in Charlotte, several mills were located on the edge of the city or just beyond the city limits, but despite

neighboring urbanity, mill villages were still constructed, lending credence to the notion of the mill owner's desire for control of his operatives.

By 1920, an estimated one-sixth of the state's white population lived in mill villages. Columbia's first post-Civil War mill was the Congaree Manufacturing Company, a small, steam-powered operation that proved unsuccessful and lasted only about three years. Three other mills began operating around the turn of the twentieth century. Founded in 1894, Columbia Mills Company was the first mill in the United States to be powered entirely with electricity. The Palmetto Cotton Mills opened in 1899 and the Glencoe Cotton Mill began operations in 1909. Four other Columbia mills date from the textile boom-period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: Richland Cotton Mills Company (1895), Granby Cotton Mills Company (1897), Olympia Cotton Mills (1899), and the Capital City Mills (1900). Although the Richland Mill was a steam-powered facility, the other mills took advantage of the electricity produced at the recently completed hydroelectric plant on the Columbia Canal. Whaley and Company designed and managed these mills, collectively known as the Whaley Mills, and they represent the firm's most advanced and innovative designs.

The Whaley Mills, on the city's southern edge and easily visible from the State House, brought the New South economy to the capital as well as the poverty associated with mill villages. Workers labored from six in the morning to 6:30 p.m. Monday through Friday and for nine hours on Saturday for wages that were, on average, sixty-percent lower than those earned by mill hands in other parts of the country. An 1896 "Christmas tree" benefit for impoverished children sponsored by The State, had to be postponed from its Christmas Eve date to December twenty-sixth when it was discovered that most of the beneficiaries would be working at the mills on Christmas Eve, but would have a half day off on Saturday, the twenty-sixth. By the following year, the Columbia Ladies' Benevolent Society was one of many local charities becoming overwhelmed by requests for assistance and appealing to the public for more help: "Since the establishment of more factories, there is a greater number of cases calling for relief, and the illness of the past summer among this class, as well as among others, having depleted our treasury, we ask contributions from the generous hearted, whose sympathies abound for the poor."

In 1907, when August Kohn wrote The Cotton Mills of South Carolina, two thousand thirty-six people worked in the four Whaley Mills. Of those, officials reported to Kohn that only thirty-two were under the age of twelve, but Kohn notes, "every mill did not freely give the desired data." Kohn reported that of the three hundred fifty children living in the Olympia mill village, only one hundred and forty attended school. This was despite the fact that a 1903 South Carolina law directed that no child under ten could be employed in a factory, mine, or mill. The age increased to eleven in 1904 and to twelve in 1905.

Mill owners and operators maintained control of the low-paid operatives and minimized complaints about hours, wages, and working conditions through well-applied paternalism. By providing housing that was often better than that the operatives had left behind in the country, schools, churches, recreational, and health facilities, owners convinced both workers and the public that the company was taking care of its own. In reality, however, schools were poorly run and were often over-crowded or under-attended, housing was sometimes sub-standard, churches were "designed less for the encouragement of religion than for its control," and the company maintained price controls at the store, often assisting in the operative's descent into debt. Like the mill's bell or whistle wafting into the mill house dictating the beginning and end of every shift, the company had access to every aspect of the operative's life.

Broadus Mitchell, in his 1930 book, The Industrial Revolution in the South, wrote, "The church and the school, not to speak of the welfare departments, have been sponsored and contributed to by the employers, and have been engines of his will and servers of his convenience." He went on to say that operatives have been "stall fed," receiving "a considerable part of their compensation in kind – gardens, medical attention, free pasturage, wood and coal at cost, and, above all, exceedingly low rents." In this situation, workers were bound to the mill because they had little cash and operatives generally accepted the services of the mill in exchange for their silence about unsafe working environments and unsanitary living conditions. Mitchell acknowledged that textile mills provided employment to a segment of the rural population (poor, landless whites) that was often living in abject poverty, but he felt that "the company-owned mill village has some time since become a means of repression of the worker, consciously maintained by the employer."

Mitchell was not the only writer discussing the paternalism of the textile mill.

Paul Blanshard, writing for the New Republic in 1927, reported, "What the mill workers gain in well repaired roofs and inside toilets, they lose in community control....The worker has neither standing as a citizen nor training for citizenship apart from the dominant figure of his industrial overlord." Indicating that the services provided by the company stifled reform, he wrote, "Social workers hired by kindly mill owners give excellent personal service, but they are not free to criticize the worst features of village life." By providing housing and other assistance to operatives, mill management hoped to stay beyond reproach in the eyes of the workers and the public. In Columbia, where since 1891 Labor Day had been celebrated with unusual gusto, labor unrest arrived early.

The National Union of Textile Workers participated in the 1900 Labor Day parade and began a call for child labor legislation, the establishment of a state bureau of labor with inspection powers, and reduced working hours. Although The State reported, "Labor organizations have cut no figure here. The people are satisfied with a good living and want no disturbance of the amicable relations between capital and themselves," the management of the Whaley Mills nervously announced plans to build a public hall, library, and school and donate land and money towards the construction of a

church. This did not pacify workers and by August 1901, with many of his workers planning to march in the Labor Day parade, Whaley ordered operatives to work overtime to make up their lost hours in advance of the parade. When the mill hands failed to work overtime on Saturday, they found themselves locked out on Monday morning. On August 28, mill employees went on strike, but the mills continued to run and strikers were given eviction notices. Whaley, however, did not like The State's coverage of the strike. He denounced the press, and thus lost a potentially valuable ally. Ultimately, with the union unable to offer meaningful financial assistance to the strikers, the strike fizzled and just four months later, workers presented Whaley with a gold watch for Christmas.

************************************************************