Francis Topeah Lafontaine: Topeah means Frost on Leaves

As a youth, Lafontaine was described as "tall, spare and athletic" noted for fitness of foot. In his later years, however, he weighed about 350 lbs.

Although Lafontaine did not receive as many sections of land through the treaties as some of the other chiefs, he was able to acquire other large holdings.

Cheif Jean-Baptiste Richardville died on August 13, 1841. George W. Ewing, the Logansport trader, wrote to Allen Hamilton on August 14, 1841, describing the various candidates for chief. Lafontaine was Ewing's second choice for chief. Ewing's first choice was Osandeah because Ewing felt that he would be in favor of paying "all the just debts and removing West." Ewing supposed that Lafontaine would be considered "a safe man. Yet he will not consent to move west I presume." Chief Chapine, successfully championed the new chief.

Lafontaine was elected civil chief at a tribal council meeting in Black Loon's Village (present day Andrews, Indiana). Francis defeated Meshingomesia and Jean Baptiste Brouillette in the election. The tribe did not even consider Richardville's surviving son, Meaquah, or any of his grandsons for the post.

After Richardville's death, Francis operated Richardville's store at the Forks of the Wabash, west of present day Huntington, Indiana. Lafontaine's election as principal chief made him the major spokesman for the tribe, as well as the guardian of their finances. The village subchiefs were responsible for the peaceful settlement of any claims for damages committed by Indians against whites.

The traders must have sensed that Francis was young and pliable and would be more accepting of their demands than Richardville. Their assessment was not mistaken, for he turned over the entire annual payment of $12,500 from the 1840 treaty to various creditors of the Miami without any written agreement.

Matters of land ownership & transfer occupied most of Lafontaine's time. They were also the main problems that blocked emigration to the Kansas.

In August 1845, a delegation of five Miami leaders traveled to Kansas territory to inspect the new reservation. Francis did not go on the inspection; instead, he sent his oldest son, Louis. The five delegates, Lewis Lafontaine, John Brouillette, Peter Pimyotamah, Chapendoceoh, and George Hunt, were not impressed. On their return trip to Indiana they met George Ewing in St. Louise and reported to him that they did not like the land and that it was a miserable place. They also told him that they would make the same report to the tribe.

Francis Lafontaine was also dragging his feet on the removal, requesting an extension on the 1845 deadline so that the land and debt concerns of the tribe could be settled. In March, 1846, the Ewing brothers reached a settlement of the outstanding Miami claims. The obtained the permission of Lafontaine and the Indian Office to obtain control of the entire $12,500 annual payment.

During the summer of 1846, Lafontaine lost his effectiveness with the other Miami leaders who were opposed to removal. In an effort to mend matters with the other leaders, he took Pimyotamah and other village chiefs on an unauthorized visit to Washington, D.C to confer with President James K. Polk. Although the tribal leadership was exempt from removal, their resistance to the move made it virtually impossible to orchestrate the removal of the rest of the tribe.

On September 22, 1846, a small group of soldiers arrived in Peru to help the agent gather the Miamis that would be transported to Kansas. The presence of the troops probably convinced Lafontaine that further delay was useless. Although Indian Agent Sinclair believed that Lafontaine was acting sincerely, he told the chief that unless the families reported to Coquillard's camp, the troops would begin to search for fugitives. The emigration finally began on October 6, 1846.

Lafontaine went west with the part of the tribe that was removed to Kansas. Shortly after Lafontaine left Kansas to return to Indiana, the tribe elected a new chief, Owl or Ozandiah. Lafontaine died on April 13, 1847 in Lafayette on his journey home from Kansas. Although members of his family believe that he had been poisoned, Lafontaine's weight and the rigors of travel are more likely causes of his death.

As a trader and businessman, Lafontaine accumulated assets worth $40,000, much of it in specie. Anson notes that there is nothing to indicate that he was ever involved in a poor business transaction.

Anson believes that Lafontaine's authority as principal chief rested on four bases: personal magnetism; undisputed leadership of his own village and family; his ability to control subchiefs of other villages who were apt to be his rivals of office and influence; and his ability to contend with white traders and the federal government.

After Lafontaine's death, the village chiefs were freed from further interference from the traders and the federal government.

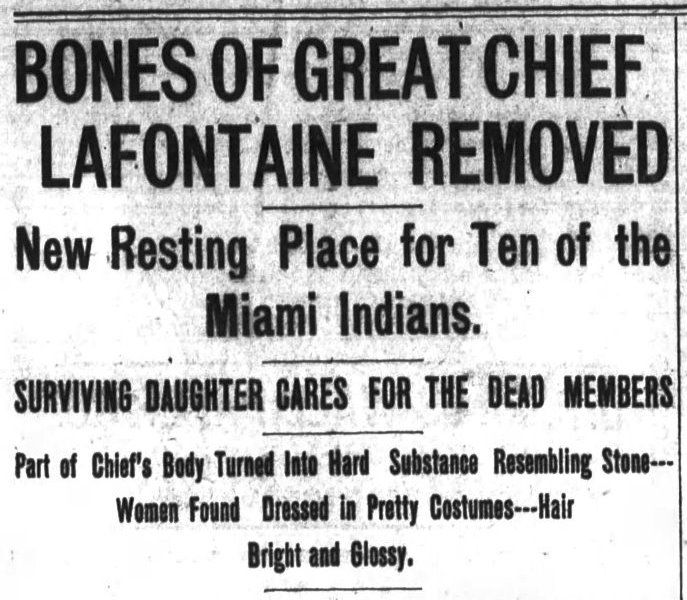

Lafontaine was buried in the St. Peter & Paul's Catholic Cemetery in Huntington. His body was moved to the Old Catholic Cemetery when the St. Peter & Paul's Cemetery grounds were used to build the school hall. Archangel Lafontaine Engleman had her father's remains moved to the Mt. Calvary Cemetery during the week of March 13, 1907. Lafontaine's body was placed in the center of a family plot where others members of the family were reburied at the same time.

The Huntington County Circuit Court appointed Rev. Julian Benoît of Fort Wayne as executor of Lafontaine's estate and John Roche, Esquire guardian of his minor children.

Lafontaine's reserve was a square mile, located west of Huntington, Indiana.

Sources:

Bert Anson - The Miami Indians - pp. 213 - 233

Stewart Rafert - The Miami Indians of Indiana, p. 100 - 101, 109 - 111, 121 - 122, 139

Fort Wayne Sentinel Newspaper Articles - December 12, 1889, March 27, 1907

Diane's Database - Diane Wolford Sheppard - Rootsweb.com; updated: August 5, 2009.

----

Chief LaFontaine was the son French-Miami Francis LaFontaine (Sr.), a friend of Chief Jean Baptiste Richardville. His French grandfather, Pierre Francois LaFontaine, was a fur trader who kept a store at Ft. Wayne's site during the American Revolution and who was a signer of the 1795 Greenville Treaty......Chief LaFpontaine was born in 1810 near Ft. Wayne and was a band Chief as early as 1832. He was related on his mother's side to Chief White Raccoon (Wa Pa Se Pah) whose reserve was east of Roanoke.....He married Cates Richardville, one of three daughters of Chief Richardville. This union was later solemnized in the 1840's with a Huntington County license and Catholic Ceremony. LaFontaine suceeded Richardville as Principle Chief in 1841. Among those with Miami Indian blood permitted to remain in the Wabash country and not be removed to Kansas, were the Meshingomesia Band, plus descendants of Richardville, Francis Godfroy, the Slocum Family and LaFontaines's family.

Information provided by SixDogTeam (46950943)

Francis Topeah Lafontaine: Topeah means Frost on Leaves

As a youth, Lafontaine was described as "tall, spare and athletic" noted for fitness of foot. In his later years, however, he weighed about 350 lbs.

Although Lafontaine did not receive as many sections of land through the treaties as some of the other chiefs, he was able to acquire other large holdings.

Cheif Jean-Baptiste Richardville died on August 13, 1841. George W. Ewing, the Logansport trader, wrote to Allen Hamilton on August 14, 1841, describing the various candidates for chief. Lafontaine was Ewing's second choice for chief. Ewing's first choice was Osandeah because Ewing felt that he would be in favor of paying "all the just debts and removing West." Ewing supposed that Lafontaine would be considered "a safe man. Yet he will not consent to move west I presume." Chief Chapine, successfully championed the new chief.

Lafontaine was elected civil chief at a tribal council meeting in Black Loon's Village (present day Andrews, Indiana). Francis defeated Meshingomesia and Jean Baptiste Brouillette in the election. The tribe did not even consider Richardville's surviving son, Meaquah, or any of his grandsons for the post.

After Richardville's death, Francis operated Richardville's store at the Forks of the Wabash, west of present day Huntington, Indiana. Lafontaine's election as principal chief made him the major spokesman for the tribe, as well as the guardian of their finances. The village subchiefs were responsible for the peaceful settlement of any claims for damages committed by Indians against whites.

The traders must have sensed that Francis was young and pliable and would be more accepting of their demands than Richardville. Their assessment was not mistaken, for he turned over the entire annual payment of $12,500 from the 1840 treaty to various creditors of the Miami without any written agreement.

Matters of land ownership & transfer occupied most of Lafontaine's time. They were also the main problems that blocked emigration to the Kansas.

In August 1845, a delegation of five Miami leaders traveled to Kansas territory to inspect the new reservation. Francis did not go on the inspection; instead, he sent his oldest son, Louis. The five delegates, Lewis Lafontaine, John Brouillette, Peter Pimyotamah, Chapendoceoh, and George Hunt, were not impressed. On their return trip to Indiana they met George Ewing in St. Louise and reported to him that they did not like the land and that it was a miserable place. They also told him that they would make the same report to the tribe.

Francis Lafontaine was also dragging his feet on the removal, requesting an extension on the 1845 deadline so that the land and debt concerns of the tribe could be settled. In March, 1846, the Ewing brothers reached a settlement of the outstanding Miami claims. The obtained the permission of Lafontaine and the Indian Office to obtain control of the entire $12,500 annual payment.

During the summer of 1846, Lafontaine lost his effectiveness with the other Miami leaders who were opposed to removal. In an effort to mend matters with the other leaders, he took Pimyotamah and other village chiefs on an unauthorized visit to Washington, D.C to confer with President James K. Polk. Although the tribal leadership was exempt from removal, their resistance to the move made it virtually impossible to orchestrate the removal of the rest of the tribe.

On September 22, 1846, a small group of soldiers arrived in Peru to help the agent gather the Miamis that would be transported to Kansas. The presence of the troops probably convinced Lafontaine that further delay was useless. Although Indian Agent Sinclair believed that Lafontaine was acting sincerely, he told the chief that unless the families reported to Coquillard's camp, the troops would begin to search for fugitives. The emigration finally began on October 6, 1846.

Lafontaine went west with the part of the tribe that was removed to Kansas. Shortly after Lafontaine left Kansas to return to Indiana, the tribe elected a new chief, Owl or Ozandiah. Lafontaine died on April 13, 1847 in Lafayette on his journey home from Kansas. Although members of his family believe that he had been poisoned, Lafontaine's weight and the rigors of travel are more likely causes of his death.

As a trader and businessman, Lafontaine accumulated assets worth $40,000, much of it in specie. Anson notes that there is nothing to indicate that he was ever involved in a poor business transaction.

Anson believes that Lafontaine's authority as principal chief rested on four bases: personal magnetism; undisputed leadership of his own village and family; his ability to control subchiefs of other villages who were apt to be his rivals of office and influence; and his ability to contend with white traders and the federal government.

After Lafontaine's death, the village chiefs were freed from further interference from the traders and the federal government.

Lafontaine was buried in the St. Peter & Paul's Catholic Cemetery in Huntington. His body was moved to the Old Catholic Cemetery when the St. Peter & Paul's Cemetery grounds were used to build the school hall. Archangel Lafontaine Engleman had her father's remains moved to the Mt. Calvary Cemetery during the week of March 13, 1907. Lafontaine's body was placed in the center of a family plot where others members of the family were reburied at the same time.

The Huntington County Circuit Court appointed Rev. Julian Benoît of Fort Wayne as executor of Lafontaine's estate and John Roche, Esquire guardian of his minor children.

Lafontaine's reserve was a square mile, located west of Huntington, Indiana.

Sources:

Bert Anson - The Miami Indians - pp. 213 - 233

Stewart Rafert - The Miami Indians of Indiana, p. 100 - 101, 109 - 111, 121 - 122, 139

Fort Wayne Sentinel Newspaper Articles - December 12, 1889, March 27, 1907

Diane's Database - Diane Wolford Sheppard - Rootsweb.com; updated: August 5, 2009.

----

Chief LaFontaine was the son French-Miami Francis LaFontaine (Sr.), a friend of Chief Jean Baptiste Richardville. His French grandfather, Pierre Francois LaFontaine, was a fur trader who kept a store at Ft. Wayne's site during the American Revolution and who was a signer of the 1795 Greenville Treaty......Chief LaFpontaine was born in 1810 near Ft. Wayne and was a band Chief as early as 1832. He was related on his mother's side to Chief White Raccoon (Wa Pa Se Pah) whose reserve was east of Roanoke.....He married Cates Richardville, one of three daughters of Chief Richardville. This union was later solemnized in the 1840's with a Huntington County license and Catholic Ceremony. LaFontaine suceeded Richardville as Principle Chief in 1841. Among those with Miami Indian blood permitted to remain in the Wabash country and not be removed to Kansas, were the Meshingomesia Band, plus descendants of Richardville, Francis Godfroy, the Slocum Family and LaFontaines's family.

Information provided by SixDogTeam (46950943)

Family Members

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement