Although intelligent he was never academic and spent much of his time as a boy getting up to larks. At 14 he finished his education and was very competent at the then standard curriculum of reading, writing and arithmetic. His first job was an errand boy to a butcher. Always highly conscientious, on the advice of his father, he decided butchery was a secure trade and at 17 commenced work in an abattoir in Bristol. He made good money and gave most of it to his mother.

At 21 he left the abattoir and became a van driver for a butcher in Gloucester Road, Bristol. In fact he could not drive but pretended a knowledge of van driving, and before he was due to start on the following Monday took several hasty driving lessons from an acquaintance who drove a van. Later, he bought a brand new Ford 8 car which was very unusual in those times, and used it to take his family on day trips to seaside towns such as Weston and Weymouth. His favourite means of relaxation was reading the Old Testament from the Bible. One day he parked his van for a lunch break in a secluded woody area called Brockley Coombe and from the balmy effects of the summer sunshine in his cab fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke it was mid afternoon and though he tried to frantically make good the lateness of his deliveries, one annoyed customer phoned his employer. He was dismissed.

A keen interest was boxing -- he stayed up all night on August 30, 1937 to listen live to the amazing Tommy Farr versus Joe Louis fight on his brother's powerful homemade radio. He occasionally did amateur boxing himself.

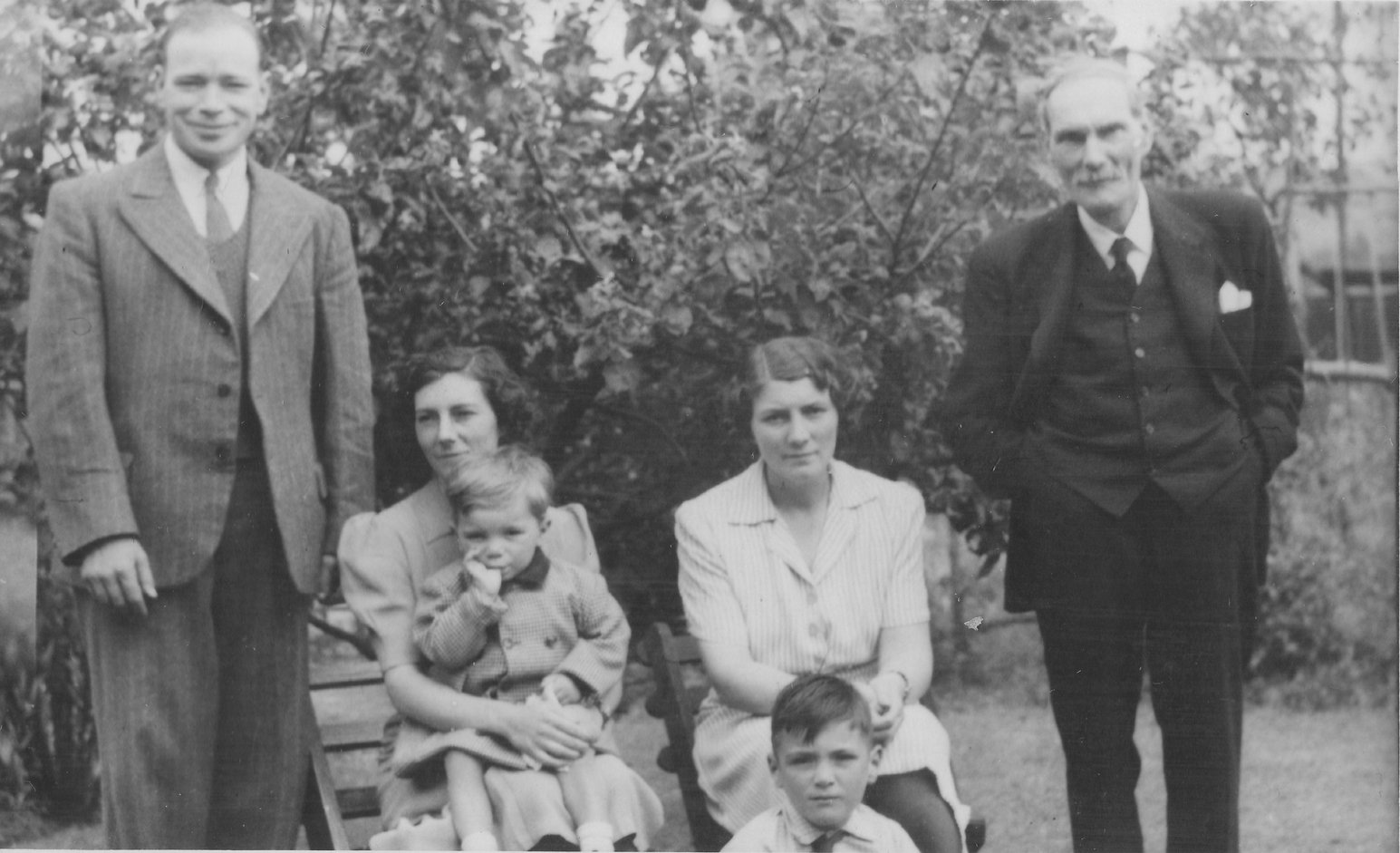

His next job was at another butchers shop: Eastman of Clifton, Bristol. There he mainly served behind the counter. In August 1939 he experienced a deep tragedy. His beloved mother, to whom he was very close, died suddenly from a heart attack aged just 53. It occurred whilst they were simply sat around as a family talking and laughing: his mother just fell back on the sofa. Her expressed fear at the coming war she never lived to experience. Also working at Eastman was a young lady of 24 years of age called Frances Wood. She was the cashier. At this time she began to think Gilbert would make a fine husband. He appeared quite handsome and appealing with golden wavy hair, pale blue eyes and a shy, very moral character. They became engaged and then married on December 14, 1940.

During the war Gilbert worked at a large aeroplane manufacturer based at Filton, Bristol. His principal task was to weld a member in the tail section. He and his wife took up cycling as there was strict rationing on petrol, tyres and other essentials for cars and would go by bicycle on day excursions but because he was always far ahead of his wife they eventually bought an expensive tandem with many gears. On one occasion she was so thirsty and exhausted on their 60 mile journey between Bristol and the seaside resort of Weston-Super-Mare and back again they decided to go into a country pub mid way and drank half a pint of strong rough cider which gave her renewed energy to get home. Their first child, a son called Graham Clive, was born in April, 1942. Before the war finished he and his wife very nearly lost their lives several times from German air raids. Their first home was destroyed even before they could move in.

In the late morning shortly before midday on September 25, 1940 he was outside working on a plane when the air raid sirens sounded, as they did almost constantly during the Battle Of Britain and the Blitz, and an enormous dark cloud resembling locusts rose from the tree covered horizon. It was a special mass air attack on his very large aircraft factory intent on obliterating it. He had to run through a hail of fighter bullets, dead and dying men and bombs falling all around to a distant air raid bunker. About half the large workforce were killed or injured in under 20 minutes. According to his recollection they would have all been killed but for two extremely brave RAF fighter pilots who for the ONLY time in the war were refuelling there. They immediately threw their cups of tea down, ran to their planes (probably Hawker Hurricane fighters which with Supermarine Spitfires and their deeply patriotic pilots won the Battle Of Britain) and ripping the fuel pipes which were still attached quickly got airborne and then turned in a distant arc and flew suicidally straight at the overwhelming mass of German fighters and bombers with their guns firing creating havoc and making them miss their target.

Gilbert's job at Filton though dangerous and hard -- sometimes having to work day and night with merely 2 hours sleep taken in exhausted desperation on the floor at the request of his kind older brother, Reginald -- had been highly paid but after the war he was not any longer needed there so he found work at Alma Garages where retaining a job became precarious. He then attempted emigration to Australia but at that time the passing whim of the government was for skilled carpenters. Always trying to improve his position he spotted a farm for sale in the West Country and as he was knowledgeable about cattle and being his own employer would be more secure and worthwhile tried unsuccessfully to raise sufficient money with his brother and form a partnership. Banks then did not give loans as they do today based on earning potential and ludicrously required the borrower to possess in some form a sum of money at least equal to the loan!

In the late 1940s he worked at Mowlem, a building firm, at which he drove a pickup truck carrying loads to the new building sites. He especially liked the friendly family atmosphere at Mowlem. His second son, Robin Julian, was born in April, 1947. Most sadly, because of contracting meningitis as a baby, he was left mentally impaired. At the beginning of the 1950s due to other men being made redundant at Mowlem he decided it would be safer to find work at St. Anne's Mill, Bristol, which was unhealthy and he disliked. Our very brave and loyal ginger cat Twinks had been a mouser there. In April 1952, his last son, Timothy John (myself) was born.

During this period he suffered much pain from kidney stones and was treated at Frenchay Hospital and then stayed at Cosham Hospital which he hated. He drank a lot of lemon barley water and finally passed the stone.

After returning to Mowlem where he was valued as a good worker the company then announced they were moving to London so in 1954 Gilbert decided he wanted the security of a government job and became a butcher at Hortham Hospital, Near Almondsbury, Bristol. He moved to Warmley, just outside Bristol, from St. Werburghs in 1955 and then finally to Westbury-on-Trym in January 1957. During this period he changed from an NSU Quickly moped to an Austin 7 car and then in 1962 a Morris Minor to commute to work. A fellow employee had been abroad and recommended he should do the same so we spent a truly wonderful holiday in the OLD France and Spain touring in the family car. In those days this was quite unusual. In fact we met an American also on holiday in France who was astonished we flew across the English Channel with the car inside the plane. His last car was a grey Worseley 1500.

Gilbert was not at all fussy about meals and would eat almost anything served. He liked good portions of plain English cuisine and two favourites were new potatoes, fresh garden peas and roast lamb with mint sauce and gravy for dinner and apple pie for tea. He was a poor cook himself and his stew was a family joke. When I was 6 my mother spent 10 days in hospital and he enthusiastically made a rice pudding for me. My spoon bent and it was impossible to eat. He had used the entire packet of rice and the result was as tough as a car tyre! Although he very seldom ate sweets and almost never drank alcohol a box of chocolates at Christmas would vanish in minutes with a glass of Harvey's sherry or port.

He hated being alone and loved window shopping which led to buying unwanted items and then finding he had too little money left for groceries so I had to tag along from a young boy onwards and kept a watch on him!

The sea had a special attraction for him and towards the end of his life he would liked to have retired and owned a large sailing boat to sail around the world. He adored looking at boats wherever he went. And piers were always a place to catch crabs. He once caught a very large crab at Bournemouth, Devon in the early 1950s and tried to repeat this in subsequent holidays. And on a holiday at Newquay, Cornwall in June 1960 he caught 18 mostly large mackerel in about 40 minutes on a fishing boat. He was offered live bait but refused and to everyone's amusement used a piece of silver foil from his cigarette packet which was much more effective. In spite of mackerel being one of our favourite tasty fish to eat, after all meals for three days having to be this because we had no fridge (only buckets of cold water kept in a shady place) our enthusiasm temporarily waned. Amusingly, whenever my mother cleared our plates and went to the refuse bins she disappeared amongst a swarm of jubilant seagulls.

In the late summer of 1963 shortly after returning from this holiday abroad he suffered two heart attacks and took two breaks of six weeks to recover. Two major contributory factors to his illness being as a butcher he especially enjoyed meat and meat fat and had smoked since about 15 years of age up to fourteen cigarettes a day. Like his father these were always Woodbine cigarettes. His favourite sister, Ethel, who had prepared meals for him before he had left home to marry and who had lived mostly an unhappy life passed away from a blood clot in her leg on May 6, 1966 which deeply upset him. She was a private piano tutor and only 50. After seven years of regular bouts of intense chest pain, though more careful about his diet and taking daily medication, he died suddenly at 11:18 pm just after retiring to bed from a severe heart attack on September 10, 1970, aged 56. The last words he ever spoke to me were ... "Good night, God bless." He was buried on September 17 at about 1:30 p.m. with many genuine mourners in attendance.

Physically very strong and prone to fleeting irrational moods, he was also a truly good family man. Highly moral, industrious, sentimental and brave. He was a fine amateur carpenter too. Although basically practical and ordinary with a mild general distaste for books of an intellectual type and most music, my dear father was subtly intelligent and very sensitive and kind hearted. I never knew him to ever lie. He was one of the very best from a now vanished truly better age in England when the only frustrations were war and a much overstated lack of prosperity. An age that promoted principles, truth and decency and appreciated them whenever they appeared; an age of honest freedom, patriotism, romance and lofty ideas ... so very different to the present world.

Although intelligent he was never academic and spent much of his time as a boy getting up to larks. At 14 he finished his education and was very competent at the then standard curriculum of reading, writing and arithmetic. His first job was an errand boy to a butcher. Always highly conscientious, on the advice of his father, he decided butchery was a secure trade and at 17 commenced work in an abattoir in Bristol. He made good money and gave most of it to his mother.

At 21 he left the abattoir and became a van driver for a butcher in Gloucester Road, Bristol. In fact he could not drive but pretended a knowledge of van driving, and before he was due to start on the following Monday took several hasty driving lessons from an acquaintance who drove a van. Later, he bought a brand new Ford 8 car which was very unusual in those times, and used it to take his family on day trips to seaside towns such as Weston and Weymouth. His favourite means of relaxation was reading the Old Testament from the Bible. One day he parked his van for a lunch break in a secluded woody area called Brockley Coombe and from the balmy effects of the summer sunshine in his cab fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke it was mid afternoon and though he tried to frantically make good the lateness of his deliveries, one annoyed customer phoned his employer. He was dismissed.

A keen interest was boxing -- he stayed up all night on August 30, 1937 to listen live to the amazing Tommy Farr versus Joe Louis fight on his brother's powerful homemade radio. He occasionally did amateur boxing himself.

His next job was at another butchers shop: Eastman of Clifton, Bristol. There he mainly served behind the counter. In August 1939 he experienced a deep tragedy. His beloved mother, to whom he was very close, died suddenly from a heart attack aged just 53. It occurred whilst they were simply sat around as a family talking and laughing: his mother just fell back on the sofa. Her expressed fear at the coming war she never lived to experience. Also working at Eastman was a young lady of 24 years of age called Frances Wood. She was the cashier. At this time she began to think Gilbert would make a fine husband. He appeared quite handsome and appealing with golden wavy hair, pale blue eyes and a shy, very moral character. They became engaged and then married on December 14, 1940.

During the war Gilbert worked at a large aeroplane manufacturer based at Filton, Bristol. His principal task was to weld a member in the tail section. He and his wife took up cycling as there was strict rationing on petrol, tyres and other essentials for cars and would go by bicycle on day excursions but because he was always far ahead of his wife they eventually bought an expensive tandem with many gears. On one occasion she was so thirsty and exhausted on their 60 mile journey between Bristol and the seaside resort of Weston-Super-Mare and back again they decided to go into a country pub mid way and drank half a pint of strong rough cider which gave her renewed energy to get home. Their first child, a son called Graham Clive, was born in April, 1942. Before the war finished he and his wife very nearly lost their lives several times from German air raids. Their first home was destroyed even before they could move in.

In the late morning shortly before midday on September 25, 1940 he was outside working on a plane when the air raid sirens sounded, as they did almost constantly during the Battle Of Britain and the Blitz, and an enormous dark cloud resembling locusts rose from the tree covered horizon. It was a special mass air attack on his very large aircraft factory intent on obliterating it. He had to run through a hail of fighter bullets, dead and dying men and bombs falling all around to a distant air raid bunker. About half the large workforce were killed or injured in under 20 minutes. According to his recollection they would have all been killed but for two extremely brave RAF fighter pilots who for the ONLY time in the war were refuelling there. They immediately threw their cups of tea down, ran to their planes (probably Hawker Hurricane fighters which with Supermarine Spitfires and their deeply patriotic pilots won the Battle Of Britain) and ripping the fuel pipes which were still attached quickly got airborne and then turned in a distant arc and flew suicidally straight at the overwhelming mass of German fighters and bombers with their guns firing creating havoc and making them miss their target.

Gilbert's job at Filton though dangerous and hard -- sometimes having to work day and night with merely 2 hours sleep taken in exhausted desperation on the floor at the request of his kind older brother, Reginald -- had been highly paid but after the war he was not any longer needed there so he found work at Alma Garages where retaining a job became precarious. He then attempted emigration to Australia but at that time the passing whim of the government was for skilled carpenters. Always trying to improve his position he spotted a farm for sale in the West Country and as he was knowledgeable about cattle and being his own employer would be more secure and worthwhile tried unsuccessfully to raise sufficient money with his brother and form a partnership. Banks then did not give loans as they do today based on earning potential and ludicrously required the borrower to possess in some form a sum of money at least equal to the loan!

In the late 1940s he worked at Mowlem, a building firm, at which he drove a pickup truck carrying loads to the new building sites. He especially liked the friendly family atmosphere at Mowlem. His second son, Robin Julian, was born in April, 1947. Most sadly, because of contracting meningitis as a baby, he was left mentally impaired. At the beginning of the 1950s due to other men being made redundant at Mowlem he decided it would be safer to find work at St. Anne's Mill, Bristol, which was unhealthy and he disliked. Our very brave and loyal ginger cat Twinks had been a mouser there. In April 1952, his last son, Timothy John (myself) was born.

During this period he suffered much pain from kidney stones and was treated at Frenchay Hospital and then stayed at Cosham Hospital which he hated. He drank a lot of lemon barley water and finally passed the stone.

After returning to Mowlem where he was valued as a good worker the company then announced they were moving to London so in 1954 Gilbert decided he wanted the security of a government job and became a butcher at Hortham Hospital, Near Almondsbury, Bristol. He moved to Warmley, just outside Bristol, from St. Werburghs in 1955 and then finally to Westbury-on-Trym in January 1957. During this period he changed from an NSU Quickly moped to an Austin 7 car and then in 1962 a Morris Minor to commute to work. A fellow employee had been abroad and recommended he should do the same so we spent a truly wonderful holiday in the OLD France and Spain touring in the family car. In those days this was quite unusual. In fact we met an American also on holiday in France who was astonished we flew across the English Channel with the car inside the plane. His last car was a grey Worseley 1500.

Gilbert was not at all fussy about meals and would eat almost anything served. He liked good portions of plain English cuisine and two favourites were new potatoes, fresh garden peas and roast lamb with mint sauce and gravy for dinner and apple pie for tea. He was a poor cook himself and his stew was a family joke. When I was 6 my mother spent 10 days in hospital and he enthusiastically made a rice pudding for me. My spoon bent and it was impossible to eat. He had used the entire packet of rice and the result was as tough as a car tyre! Although he very seldom ate sweets and almost never drank alcohol a box of chocolates at Christmas would vanish in minutes with a glass of Harvey's sherry or port.

He hated being alone and loved window shopping which led to buying unwanted items and then finding he had too little money left for groceries so I had to tag along from a young boy onwards and kept a watch on him!

The sea had a special attraction for him and towards the end of his life he would liked to have retired and owned a large sailing boat to sail around the world. He adored looking at boats wherever he went. And piers were always a place to catch crabs. He once caught a very large crab at Bournemouth, Devon in the early 1950s and tried to repeat this in subsequent holidays. And on a holiday at Newquay, Cornwall in June 1960 he caught 18 mostly large mackerel in about 40 minutes on a fishing boat. He was offered live bait but refused and to everyone's amusement used a piece of silver foil from his cigarette packet which was much more effective. In spite of mackerel being one of our favourite tasty fish to eat, after all meals for three days having to be this because we had no fridge (only buckets of cold water kept in a shady place) our enthusiasm temporarily waned. Amusingly, whenever my mother cleared our plates and went to the refuse bins she disappeared amongst a swarm of jubilant seagulls.

In the late summer of 1963 shortly after returning from this holiday abroad he suffered two heart attacks and took two breaks of six weeks to recover. Two major contributory factors to his illness being as a butcher he especially enjoyed meat and meat fat and had smoked since about 15 years of age up to fourteen cigarettes a day. Like his father these were always Woodbine cigarettes. His favourite sister, Ethel, who had prepared meals for him before he had left home to marry and who had lived mostly an unhappy life passed away from a blood clot in her leg on May 6, 1966 which deeply upset him. She was a private piano tutor and only 50. After seven years of regular bouts of intense chest pain, though more careful about his diet and taking daily medication, he died suddenly at 11:18 pm just after retiring to bed from a severe heart attack on September 10, 1970, aged 56. The last words he ever spoke to me were ... "Good night, God bless." He was buried on September 17 at about 1:30 p.m. with many genuine mourners in attendance.

Physically very strong and prone to fleeting irrational moods, he was also a truly good family man. Highly moral, industrious, sentimental and brave. He was a fine amateur carpenter too. Although basically practical and ordinary with a mild general distaste for books of an intellectual type and most music, my dear father was subtly intelligent and very sensitive and kind hearted. I never knew him to ever lie. He was one of the very best from a now vanished truly better age in England when the only frustrations were war and a much overstated lack of prosperity. An age that promoted principles, truth and decency and appreciated them whenever they appeared; an age of honest freedom, patriotism, romance and lofty ideas ... so very different to the present world.