Funeral services will be held at the family owned Ruck Towson Funeral Home Inc., 1050 York Rd (beltway exit 26) on Wednesday at 11 A.M.

Interment Gardens of Faith Cemetery. Friends may call on Tuesday from 6 to 8 P.M.

In lieu of flowers contributions to the

Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund

Suite 901

1611 Kent Street

Arlington, VA 22209

Obituary from www.baltimoresun.com

A beautiful tribute, also from the Baltimore Sun, by Peter Hermann

Strangers come to honor retired police wagon man who died alone

One by one, they stood and walked up the blue carpet to the front of the chapel to pay their respects to Edward William Eldridge Jr.

They were retired police colonels and active police majors in dress blues, black mourning bands stretched across their badges. A current Baltimore councilwoman and a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives. A police chaplain and a war veteran. The Baltimore County state's attorney. Neighbors, one-time friends and former colleagues.

Strangers who felt it necessary to say goodbye.

There were no relatives.

Edward William Eldridge died alone at the age of 62, a decade after retiring from a quarter-century as a patrolman for the Baltimore Police Department. He took his own life last month in the small Northeast Baltimore home in which he had grown up by shooting himself in the head.

He had no family to claim the body, no close friends to plan a funeral. Instead, the homicide detective who investigated, Randy Wynn, plowed through his former colleague's papers, claimed the body and organized a service at Ruck Funeral Home in Towson. More than 150 attended Tuesday's viewing - including the city police commissioner and two of his predecessors.

Yesterday, another 100 came - not just to mourn, but to challenge themselves and each other to seek out old friends and neighbors, retired colleagues and dying relatives, and make sure they don't end up alone like the man they now honored, lying in a flag-draped coffin surrounded by flowers sent by people he didn't know.

Wesley M. Ormrod never met Eldridge. "I want to be sure that in death he knew he had a family," the retired Baltimore police lieutenant said.

A police chaplain, Don Helms, read comments from Eldridge's personnel file: strong worker; quiet; helps fellow officers; very aggressive. When he applied to the force in 1972, a supervisor asked him why he wanted to be an officer. "Because I want to help people who have no place to turn for help," he answered.

In the end, in his upstairs bedroom on Daywalt Avenue, Eldridge was one of the people who felt he had no place to turn for help. He wrote in his suicide note that he couldn't find someone to stay with him at the hospital for a routine surgery. He didn't write that he also had lost most of his retirement money to the stock market and had recently been assaulted and robbed.

His death stunned the law enforcement community and sparked discussions in the union halls about how to get retirees back into the fold. There is talk of a campaign to get them computers and teach them e-mail so they will be on a network.

City Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke simply said: "We all need to do better."

Lucille Blue came from Aberdeen. She had lived across the street from Eldridge and recalled how her two sons, then 7 and 8, bounded inside one morning after a snowstorm, each clutching a crisp 20-dollar bill. "We shoveled Mr. Ed's snow," they proudly proclaimed.

Eldridge had provided the shovels and cleared most of the snow.

He fixed children's bicycles and handed out candy. He told one neighbor with a big family to use his yard. A friend of his late mother's invited him to family gatherings but stopped when he didn't attend. Blue had offered him her number when she moved a few years ago, but he never called.

"Now, I wish I had stayed in touch with him," she said.

Eldridge didn't hang out with fellow cops - he stayed away from their parties and quietly disappeared when a profanity was uttered. Colleagues simply thought he had a life beyond the department; they learned later that he had no life at all.

For years, he was the Central District's wagon man, speeding to arrests and hauling "the worst of Baltimore" to the cells, He listened to the action on the radio, anticipated an arrest and positioned his boxy van to get to the call fast when it came.

Matthew Corell came to the Central as a rookie cop in 1997 - the days when a young officer would ask for a radio and be shouted down by a stern sergeant, "You don't need a radio. Rookies don't talk."

Corell, a youngster from the county, said Eldridge helped him. "I had no idea where Pennsylvania Avenue was or what Etting Street was," Corell told mourners. "Officer Eldridge was the only senior officer who spoke to me. ... He was the only person who I thought when I came to work, 'God, I hope Eddie is working today.' "

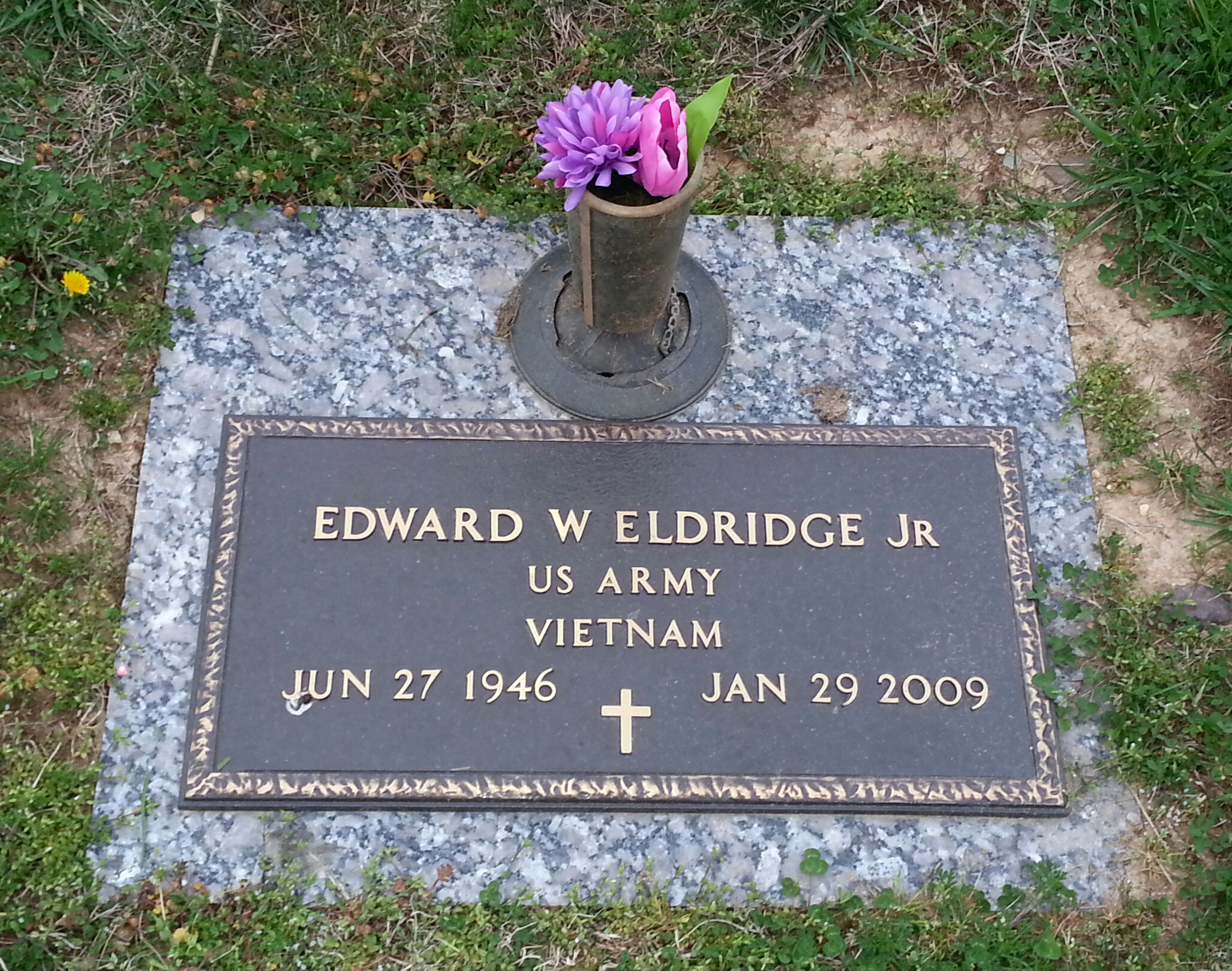

It was only a few days ago that Detective Wynn found a place to bury his former colleague. Nearly lost in stacks of paperwork, he discovered that Eldridge's late parents, Edward and Ruth, had paid for a family plot. The parents had taken care of their son beyond their years and beyond his.

The service over, pallbearers carried the coffin from the funeral home, past an honor guard and cops standing at attention. Police motorcycle officers escorted the hearse and mourners around the Beltway to the Garden of Faith Cemetery in Overlea, the final words of the police chaplain echoing:

"You may not be able to depend on anybody, but you can depend on God."

Funeral services will be held at the family owned Ruck Towson Funeral Home Inc., 1050 York Rd (beltway exit 26) on Wednesday at 11 A.M.

Interment Gardens of Faith Cemetery. Friends may call on Tuesday from 6 to 8 P.M.

In lieu of flowers contributions to the

Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund

Suite 901

1611 Kent Street

Arlington, VA 22209

Obituary from www.baltimoresun.com

A beautiful tribute, also from the Baltimore Sun, by Peter Hermann

Strangers come to honor retired police wagon man who died alone

One by one, they stood and walked up the blue carpet to the front of the chapel to pay their respects to Edward William Eldridge Jr.

They were retired police colonels and active police majors in dress blues, black mourning bands stretched across their badges. A current Baltimore councilwoman and a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives. A police chaplain and a war veteran. The Baltimore County state's attorney. Neighbors, one-time friends and former colleagues.

Strangers who felt it necessary to say goodbye.

There were no relatives.

Edward William Eldridge died alone at the age of 62, a decade after retiring from a quarter-century as a patrolman for the Baltimore Police Department. He took his own life last month in the small Northeast Baltimore home in which he had grown up by shooting himself in the head.

He had no family to claim the body, no close friends to plan a funeral. Instead, the homicide detective who investigated, Randy Wynn, plowed through his former colleague's papers, claimed the body and organized a service at Ruck Funeral Home in Towson. More than 150 attended Tuesday's viewing - including the city police commissioner and two of his predecessors.

Yesterday, another 100 came - not just to mourn, but to challenge themselves and each other to seek out old friends and neighbors, retired colleagues and dying relatives, and make sure they don't end up alone like the man they now honored, lying in a flag-draped coffin surrounded by flowers sent by people he didn't know.

Wesley M. Ormrod never met Eldridge. "I want to be sure that in death he knew he had a family," the retired Baltimore police lieutenant said.

A police chaplain, Don Helms, read comments from Eldridge's personnel file: strong worker; quiet; helps fellow officers; very aggressive. When he applied to the force in 1972, a supervisor asked him why he wanted to be an officer. "Because I want to help people who have no place to turn for help," he answered.

In the end, in his upstairs bedroom on Daywalt Avenue, Eldridge was one of the people who felt he had no place to turn for help. He wrote in his suicide note that he couldn't find someone to stay with him at the hospital for a routine surgery. He didn't write that he also had lost most of his retirement money to the stock market and had recently been assaulted and robbed.

His death stunned the law enforcement community and sparked discussions in the union halls about how to get retirees back into the fold. There is talk of a campaign to get them computers and teach them e-mail so they will be on a network.

City Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke simply said: "We all need to do better."

Lucille Blue came from Aberdeen. She had lived across the street from Eldridge and recalled how her two sons, then 7 and 8, bounded inside one morning after a snowstorm, each clutching a crisp 20-dollar bill. "We shoveled Mr. Ed's snow," they proudly proclaimed.

Eldridge had provided the shovels and cleared most of the snow.

He fixed children's bicycles and handed out candy. He told one neighbor with a big family to use his yard. A friend of his late mother's invited him to family gatherings but stopped when he didn't attend. Blue had offered him her number when she moved a few years ago, but he never called.

"Now, I wish I had stayed in touch with him," she said.

Eldridge didn't hang out with fellow cops - he stayed away from their parties and quietly disappeared when a profanity was uttered. Colleagues simply thought he had a life beyond the department; they learned later that he had no life at all.

For years, he was the Central District's wagon man, speeding to arrests and hauling "the worst of Baltimore" to the cells, He listened to the action on the radio, anticipated an arrest and positioned his boxy van to get to the call fast when it came.

Matthew Corell came to the Central as a rookie cop in 1997 - the days when a young officer would ask for a radio and be shouted down by a stern sergeant, "You don't need a radio. Rookies don't talk."

Corell, a youngster from the county, said Eldridge helped him. "I had no idea where Pennsylvania Avenue was or what Etting Street was," Corell told mourners. "Officer Eldridge was the only senior officer who spoke to me. ... He was the only person who I thought when I came to work, 'God, I hope Eddie is working today.' "

It was only a few days ago that Detective Wynn found a place to bury his former colleague. Nearly lost in stacks of paperwork, he discovered that Eldridge's late parents, Edward and Ruth, had paid for a family plot. The parents had taken care of their son beyond their years and beyond his.

The service over, pallbearers carried the coffin from the funeral home, past an honor guard and cops standing at attention. Police motorcycle officers escorted the hearse and mourners around the Beltway to the Garden of Faith Cemetery in Overlea, the final words of the police chaplain echoing:

"You may not be able to depend on anybody, but you can depend on God."