Peter C. House, son of Conrad and Margaretha Haus, was baptized on May 11, 1755, at Stone Arabia, Montgomery County, New York [1p394]. Peter was a descendant of Johann Christian Haus, a Palatine German immigrant who arrived with his family in New York in 1710. There is general agreement that Peter's father's name was Conrad but there is some disagreement among researchers as to whether there are one or two generations separating Peter and Johann, and whether Peter is descended from Johann's first or second wife [13].

In 1777, Peter (22) was working on the Hudson River, transporting supplies by boat to George Washington's camp at Fishkill, New York. On August 6, while he was at Fishkill, two of his brothers were killed and one was wounded at the battle of Oriskany in western New York [2] which, based on the percentage of casualties suffered, was one of the bloodiest of the Revolutionary War.

During the war, the British were determined to lay waste to New York's Schoharie and Mohawk River valleys, known as the "grain bowl" that fed Washington's armies. There were five major raids on the New York frontier made by British, Loyalist and Indian forces, each numbering more than 500 men. There were also numerous raiding parties of 10 to 20 men, burning, scalping, and kidnapping, which created a terrible uncertainty that hovered over everything. All of this was occurring in the midst of a vicious civil war that pitted neighbor against neighbor. The terror and suffering experienced by the people of the valley during those years was far greater than that of any other area of the 13 colonies. Between the years 1777 and 1781, the population of the Mohawk Valley dropped from 10,000 to 3,000 [11].

Beginning in 1779, under various commanders, Peter served as a private and corporal in the Tryon County, New York Militia and Levies [1p397;2]. In 1780, the year of the worst raids, Peter served along the Mohawk River at Fort Plain, Stone Arabia, Johnstown, Fort Herkimer, and Fort Dayton [2]. By October, he was with Harper's Regiment of Levies at Fort Stanwix, located at present-day Rome. On October 21, word reached Fort Stanwix that a major battle had occurred at Stone Arabia two days earlier [3p234]. An expedition of over 900 British, Loyalist and Indian forces had been conducting large-scale raids throughout the Schoharie and Mohawk River Valleys, an operation that had begun in early October at Oswego, on the southeastern shore of Lake Ontario. From Oswego, the raiders had sent their artillery and provisions down the Oswego River on 18 boats, to the east end of Lake Onandoga [3p164-5] (near present day Syracuse) where they had retrieved the cargo before continuing the 250 miles, mostly along narrow Indian trails [3p168], to the Schoharie Valley. After fighting skirmishes and battles, taking prisoners, burning forts, farms, and mills, and destroying one of the finest grain harvests in living memory, they were returning to the location of their boats.

Peter, part of a 60-man detachment, was immediately dispatched from Fort Stanwix to destroy the enemy boats, located about 45 miles west of the fort, before the raiding expedition could reach them [3p234]. Two days into their mission, Peter and the rest of his detachment were captured, south of Lake Oneida, at a place called Ganaghsaraga [3p236-7]. Following their capture, with an eye to deserting as soon as the first opportunity arose, 40 of the men, including Peter and 11 others from Harper's Levies, agreed to enlist in the 2nd Battalion KRR (King's Royal Regiment) [3p346]. This was not an uncommon practice for those on both sides captured during the war [3p241].

By November 1, the prisoners and their captors had traveled the 40 miles north to Oswego [3p345]. From there, they proceeded up the St. Lawrence River to a small military post at Coteau-du-lac, on the north side of the St. Lawrence, about 35 miles south-southwest of Montreal. At Coteau-du-Lac, while undergoing training and indoctrination, the new recruits were kept under close scrutiny. Adjacent to their post, in the middle of the St. Lawrence, was a small island known as Prison Island, used to house the worst of the Patriot prisoners. It was a very secure location, surrounded by rapids and extremely difficult to access [3p241-2]. Prisoners, in irons and crawling with vermin, were given no clothes other than what they had on, and no blankets or straw to sleep on [4p256]. Whether Peter or others in his party spent time on the island as prisoners, or on guard or other duty, is not clear [3p242].

The following spring, a group of prisoners at Coteau-du-Lac formed a conspiracy to kill the commanding officer of the post, kill anyone who opposed them, burn the post to the ground, and rejoin the Patriot militia. Unfortunately, their plot was discovered before it could be carried out and nine of the conspirators were arraigned before a court martial at Montreal on June 6, 1781. Among them were Peter House and five other men from his captured detachment [3pp242,346]. The decisions of the court were given on June 25. Six of the men each received 1,000 lashes upon their bare backs at the head of their regiment. Two other men each received 500 lashes. One man died from his wounds and the others were most likely crippled for life. Peter was the only man found not guilty and acquitted of all charges. When the injured men were able to travel, they were returned to prison in irons [3p243]. Peter was apparently returned with them since he remained imprisoned, perhaps on Prison Island, until the end of the war, for a total of two years and six months. He was released on May 1, 1783, and returned home.

A year and a half later, on January 11, 1785, Peter (30) married Anna Shaut (20) [1pp394,397;2], daughter of Theodorus and Mary Shaut. Reverend Abraham Rosencrantz [1p397] performed the ceremony in his home at Fall Hill [2], about a mile-and-a half south of Little Falls [5]. After their marriage, Peter and Anna lived and raised a large family in the town of Minden, southeast of Little Falls [2,8]. In the 24 years between 1788 and 1812, Anna gave birth to at least 9 children, and perhaps as many as 14 [9].

Between 1793 and 1812, Britain and France were at war. The United States struggled to maintain its neutrality, but many Americans were outraged by the British practice of searching and seizing U. S. merchant ships and impressing American sailors into service aboard British warships. Eventually, on June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain.

Having suffered years of imprisonment, Peter was undoubtedly bitter toward the British when the War of 1812 began. The memory of his two brothers being slain at Oriskany also appeared to haunt him [2]. On February 8, 1813 [1p397], at the strong objection of his wife and children, Peter (57) enlisted in Colonel John Mills' Artillery and Infantry Regiment, New York Volunteers, under Battalion Commander Major John Herkimer, in the Company of Captain David Moyer [2]. The newly assembled regiment was sent to Sackets Harbor, New York, the U. S. military headquarters for the northern frontier. Control of the Great Lakes was of critical strategic importance to both the Americans and the British and Sackets Harbor was the only harbor on the American side of Lake Ontario that could easily accommodate warships.

By the spring of 1813, the American shipbuilding effort at Sackers Harbor had produced enough ships to adequately challenge the British warships on the lake and a squadron of ships was sent to attack British Fort George, at the other end of Lake Ontario. The British, taking advantage of the Americans' absence, decided to attack Sackets Harbor. Their goal was to destroy the American facilities and, most importantly, a large new warship under construction.

On May 28, 1813, British warships, loaded with soldiers, were seen approaching Sackets Harbor. Late that rainy night, a British assault force rowed from the British fleet toward the western side of Horse Island, where part of Peter's regiment had been stationed. Horse Island, attached to the mainland at low tide by a causeway, was a small 24-acre island located about a mile south of the harbor. At sunrise, as the British attempted their landing, they drew heavy fire from the American defenders, and they were forced to move to the northern side of the island to make their landing [12].

As the large British force came ashore, those from Peter's regiment who were on the island retreated across the causeway to the mainland where the balance of their regiment and a number of militia had been stationed behind a natural breastwork on the gravelly beach. At some point during this confrontation, Peter's regimental commander was killed, and Peter received a serious leg wound.

The battle continued on the mainland as the British proceeded toward the American fortifications. Fearing that that they would fall into enemy hands, a couple of vessels and a large quantity of stores were regrettably ordered to be set on fire by one of the American lieutenants. The engagement lasted about 3 hours before the British forces were finally repulsed. Total casualties were 265 for the British and 307 for the Americans. It was a narrow victory for the Americans but their losses in men and material were significant and it delayed a planned invasion of Upper Canada.

Peter suffered considerably from his leg wound. For a month after the battle, he was cared for by Jacob Shafer, a friend and neighbor of Peter's, who had enlisted with Peter and had served with him in the same regiment. Sadly, Peter's wound became gangrenous, and he died on July 1, 1813 [2].

Five days before his death, in the presence of three witnesses, Peter made his mark on a will that he had dictated and had been written for him. It was registered on February 9, 1814. He designated his wife Anna ("Nancy") as administrator and he left most of his estate to her, including three of the best cows, seven of the best sheep, and a Fox Mare with saddle and bridle. If the Fox Mare was dead or disabled, Anna was to get the next most valuable horse. She was also to get all of the household furniture and all monetary debts owed Peter, to be collected by their oldest son Joseph. The remainder of Peter's property was to be sold at public auction the following November. Anna was to keep half of the proceeds from the sale, minus $5.00, which she was to give to their second-oldest son Conrad. The other half of the proceeds were to be given to Joseph. Any pay or benefits due Peter for his military service were to go to Anna. He also anticipated receiving 160 acres of land from the government, which Anna was free to give to whomever she desired at the time of her death. Proceeds from the current year's crops were to be used to pay any debts incurred by Peter since his absence, with the remaining balance going to Anna [6].

While stationed at Sackets Harbor, prior to his injury, Peter frequently had letters written to his wife Anna (he could not write), assuring her that he was doing well. When word reached Anna that Peter had been seriously wounded, she immediately left home to go see him. Peter had died and had been buried for five days by the time she reached Sackets Harbor [2].

The exact place of Peter's burial is unknown. There was a War of 1812 mass burial plot on the grounds that became Madison Barracks, but there are no names associated with that site. In 1909, the Madison Barracks cemetery was relocated to its present location off Dodge Avenue in Sackets Harbor [10].

Anna applied for a widow's pension in 1841. She began receiving a yearly allowance of $80, beginning in 1845, which continued until her death in 1858. [7]

Endnotes:

[1] Penrose, Maryly P., Compendium of Early Mohawk Valley Families, Vol. 1. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1990.

[2] Affidavit by Anna House, wife of Peter C. House, Revolutionary War Pension file of Peter C. House, State of New York, Herkimer County, 4 Oct 1841.

[3] Watt, Gavin K., The Burning of the Valleys; Dundrum Press, Toronto; 1997.

[4] Watt, Gavin K., I am heartily ashamed: Volume II: The Revolutionary War's Final Campaign as Waged from Canada in 1782; Dundurn Publishing.

[5] Old map showing location of A. Rosencrantz home; Herkimer County Historical Society

[6] Will of Peter C. House, dated 26 Jun 1813. State of New York, Montgomery County Surrogate's Court, New Courthouse, Room 50, 58 Broadway, P. O. Box 1500, Fonda, NY 12068-1500. Copy of original transcribed by Lawrence E. House, II, July 2011.

[7] Pension records for Peter C. House

[8] 1800 U. S. Census, Town of Minden, New York

[9] Due to the scarcity of records, it is difficult to identify all members of large families during this time period. The petition for the administration of Anna's estate in 1858 identifies 5 sons (1 deceased) and 4 daughters. Genealogies prepared from other sources by researchers L. H. Shults, Kathleen Fenton and Ross Eckler identify 5 additional children, 3 of whom supposedly died young.

[10] Barone, Constance, Sackets Harbor Site Manager, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

[11] Horton, Gerald, Horton's Historical Articles, http://hortonsarticles.org/hh7thousand.htm ; 10 Jun 2009.

[12] Morris, John D., Sword of the Border: Major Jacob Jennings Brown, 1775-1828.

[13] One generation and first wife: Ken Johnson and Sylvia Novak. Two generations and first wife: L. H. Shults and David Stanley. Two generations and second wife: Roy Francis Howes and Marsha Strong. Howes, Strong and Stanley say Peter's father was killed at Oriskany but Anna's affidavit says Peter's two brothers were killed, not his father.

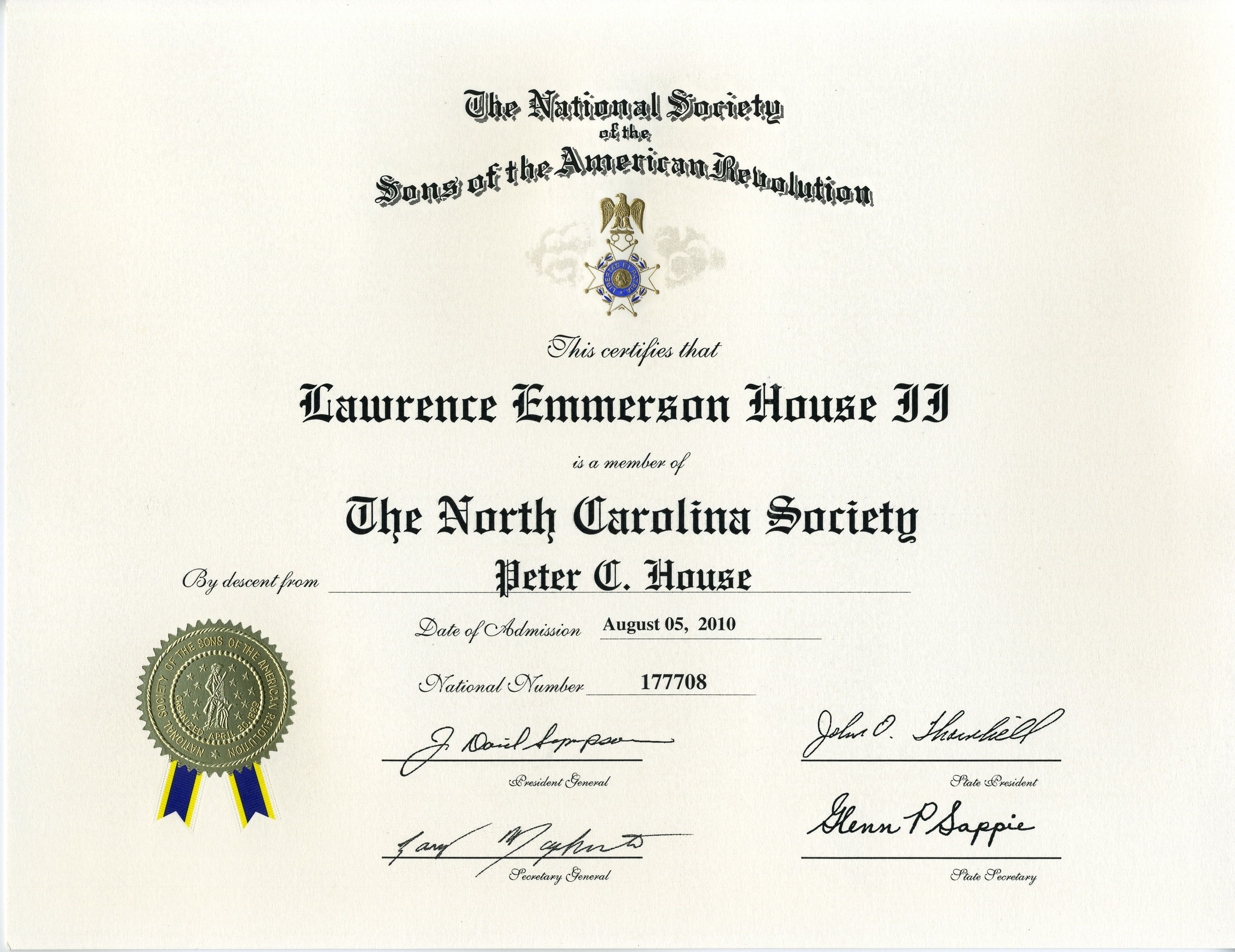

Compiled by Lawrence E. House, II - 4th great grandson of Peter C. House

Peter C. House, son of Conrad and Margaretha Haus, was baptized on May 11, 1755, at Stone Arabia, Montgomery County, New York [1p394]. Peter was a descendant of Johann Christian Haus, a Palatine German immigrant who arrived with his family in New York in 1710. There is general agreement that Peter's father's name was Conrad but there is some disagreement among researchers as to whether there are one or two generations separating Peter and Johann, and whether Peter is descended from Johann's first or second wife [13].

In 1777, Peter (22) was working on the Hudson River, transporting supplies by boat to George Washington's camp at Fishkill, New York. On August 6, while he was at Fishkill, two of his brothers were killed and one was wounded at the battle of Oriskany in western New York [2] which, based on the percentage of casualties suffered, was one of the bloodiest of the Revolutionary War.

During the war, the British were determined to lay waste to New York's Schoharie and Mohawk River valleys, known as the "grain bowl" that fed Washington's armies. There were five major raids on the New York frontier made by British, Loyalist and Indian forces, each numbering more than 500 men. There were also numerous raiding parties of 10 to 20 men, burning, scalping, and kidnapping, which created a terrible uncertainty that hovered over everything. All of this was occurring in the midst of a vicious civil war that pitted neighbor against neighbor. The terror and suffering experienced by the people of the valley during those years was far greater than that of any other area of the 13 colonies. Between the years 1777 and 1781, the population of the Mohawk Valley dropped from 10,000 to 3,000 [11].

Beginning in 1779, under various commanders, Peter served as a private and corporal in the Tryon County, New York Militia and Levies [1p397;2]. In 1780, the year of the worst raids, Peter served along the Mohawk River at Fort Plain, Stone Arabia, Johnstown, Fort Herkimer, and Fort Dayton [2]. By October, he was with Harper's Regiment of Levies at Fort Stanwix, located at present-day Rome. On October 21, word reached Fort Stanwix that a major battle had occurred at Stone Arabia two days earlier [3p234]. An expedition of over 900 British, Loyalist and Indian forces had been conducting large-scale raids throughout the Schoharie and Mohawk River Valleys, an operation that had begun in early October at Oswego, on the southeastern shore of Lake Ontario. From Oswego, the raiders had sent their artillery and provisions down the Oswego River on 18 boats, to the east end of Lake Onandoga [3p164-5] (near present day Syracuse) where they had retrieved the cargo before continuing the 250 miles, mostly along narrow Indian trails [3p168], to the Schoharie Valley. After fighting skirmishes and battles, taking prisoners, burning forts, farms, and mills, and destroying one of the finest grain harvests in living memory, they were returning to the location of their boats.

Peter, part of a 60-man detachment, was immediately dispatched from Fort Stanwix to destroy the enemy boats, located about 45 miles west of the fort, before the raiding expedition could reach them [3p234]. Two days into their mission, Peter and the rest of his detachment were captured, south of Lake Oneida, at a place called Ganaghsaraga [3p236-7]. Following their capture, with an eye to deserting as soon as the first opportunity arose, 40 of the men, including Peter and 11 others from Harper's Levies, agreed to enlist in the 2nd Battalion KRR (King's Royal Regiment) [3p346]. This was not an uncommon practice for those on both sides captured during the war [3p241].

By November 1, the prisoners and their captors had traveled the 40 miles north to Oswego [3p345]. From there, they proceeded up the St. Lawrence River to a small military post at Coteau-du-lac, on the north side of the St. Lawrence, about 35 miles south-southwest of Montreal. At Coteau-du-Lac, while undergoing training and indoctrination, the new recruits were kept under close scrutiny. Adjacent to their post, in the middle of the St. Lawrence, was a small island known as Prison Island, used to house the worst of the Patriot prisoners. It was a very secure location, surrounded by rapids and extremely difficult to access [3p241-2]. Prisoners, in irons and crawling with vermin, were given no clothes other than what they had on, and no blankets or straw to sleep on [4p256]. Whether Peter or others in his party spent time on the island as prisoners, or on guard or other duty, is not clear [3p242].

The following spring, a group of prisoners at Coteau-du-Lac formed a conspiracy to kill the commanding officer of the post, kill anyone who opposed them, burn the post to the ground, and rejoin the Patriot militia. Unfortunately, their plot was discovered before it could be carried out and nine of the conspirators were arraigned before a court martial at Montreal on June 6, 1781. Among them were Peter House and five other men from his captured detachment [3pp242,346]. The decisions of the court were given on June 25. Six of the men each received 1,000 lashes upon their bare backs at the head of their regiment. Two other men each received 500 lashes. One man died from his wounds and the others were most likely crippled for life. Peter was the only man found not guilty and acquitted of all charges. When the injured men were able to travel, they were returned to prison in irons [3p243]. Peter was apparently returned with them since he remained imprisoned, perhaps on Prison Island, until the end of the war, for a total of two years and six months. He was released on May 1, 1783, and returned home.

A year and a half later, on January 11, 1785, Peter (30) married Anna Shaut (20) [1pp394,397;2], daughter of Theodorus and Mary Shaut. Reverend Abraham Rosencrantz [1p397] performed the ceremony in his home at Fall Hill [2], about a mile-and-a half south of Little Falls [5]. After their marriage, Peter and Anna lived and raised a large family in the town of Minden, southeast of Little Falls [2,8]. In the 24 years between 1788 and 1812, Anna gave birth to at least 9 children, and perhaps as many as 14 [9].

Between 1793 and 1812, Britain and France were at war. The United States struggled to maintain its neutrality, but many Americans were outraged by the British practice of searching and seizing U. S. merchant ships and impressing American sailors into service aboard British warships. Eventually, on June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain.

Having suffered years of imprisonment, Peter was undoubtedly bitter toward the British when the War of 1812 began. The memory of his two brothers being slain at Oriskany also appeared to haunt him [2]. On February 8, 1813 [1p397], at the strong objection of his wife and children, Peter (57) enlisted in Colonel John Mills' Artillery and Infantry Regiment, New York Volunteers, under Battalion Commander Major John Herkimer, in the Company of Captain David Moyer [2]. The newly assembled regiment was sent to Sackets Harbor, New York, the U. S. military headquarters for the northern frontier. Control of the Great Lakes was of critical strategic importance to both the Americans and the British and Sackets Harbor was the only harbor on the American side of Lake Ontario that could easily accommodate warships.

By the spring of 1813, the American shipbuilding effort at Sackers Harbor had produced enough ships to adequately challenge the British warships on the lake and a squadron of ships was sent to attack British Fort George, at the other end of Lake Ontario. The British, taking advantage of the Americans' absence, decided to attack Sackets Harbor. Their goal was to destroy the American facilities and, most importantly, a large new warship under construction.

On May 28, 1813, British warships, loaded with soldiers, were seen approaching Sackets Harbor. Late that rainy night, a British assault force rowed from the British fleet toward the western side of Horse Island, where part of Peter's regiment had been stationed. Horse Island, attached to the mainland at low tide by a causeway, was a small 24-acre island located about a mile south of the harbor. At sunrise, as the British attempted their landing, they drew heavy fire from the American defenders, and they were forced to move to the northern side of the island to make their landing [12].

As the large British force came ashore, those from Peter's regiment who were on the island retreated across the causeway to the mainland where the balance of their regiment and a number of militia had been stationed behind a natural breastwork on the gravelly beach. At some point during this confrontation, Peter's regimental commander was killed, and Peter received a serious leg wound.

The battle continued on the mainland as the British proceeded toward the American fortifications. Fearing that that they would fall into enemy hands, a couple of vessels and a large quantity of stores were regrettably ordered to be set on fire by one of the American lieutenants. The engagement lasted about 3 hours before the British forces were finally repulsed. Total casualties were 265 for the British and 307 for the Americans. It was a narrow victory for the Americans but their losses in men and material were significant and it delayed a planned invasion of Upper Canada.

Peter suffered considerably from his leg wound. For a month after the battle, he was cared for by Jacob Shafer, a friend and neighbor of Peter's, who had enlisted with Peter and had served with him in the same regiment. Sadly, Peter's wound became gangrenous, and he died on July 1, 1813 [2].

Five days before his death, in the presence of three witnesses, Peter made his mark on a will that he had dictated and had been written for him. It was registered on February 9, 1814. He designated his wife Anna ("Nancy") as administrator and he left most of his estate to her, including three of the best cows, seven of the best sheep, and a Fox Mare with saddle and bridle. If the Fox Mare was dead or disabled, Anna was to get the next most valuable horse. She was also to get all of the household furniture and all monetary debts owed Peter, to be collected by their oldest son Joseph. The remainder of Peter's property was to be sold at public auction the following November. Anna was to keep half of the proceeds from the sale, minus $5.00, which she was to give to their second-oldest son Conrad. The other half of the proceeds were to be given to Joseph. Any pay or benefits due Peter for his military service were to go to Anna. He also anticipated receiving 160 acres of land from the government, which Anna was free to give to whomever she desired at the time of her death. Proceeds from the current year's crops were to be used to pay any debts incurred by Peter since his absence, with the remaining balance going to Anna [6].

While stationed at Sackets Harbor, prior to his injury, Peter frequently had letters written to his wife Anna (he could not write), assuring her that he was doing well. When word reached Anna that Peter had been seriously wounded, she immediately left home to go see him. Peter had died and had been buried for five days by the time she reached Sackets Harbor [2].

The exact place of Peter's burial is unknown. There was a War of 1812 mass burial plot on the grounds that became Madison Barracks, but there are no names associated with that site. In 1909, the Madison Barracks cemetery was relocated to its present location off Dodge Avenue in Sackets Harbor [10].

Anna applied for a widow's pension in 1841. She began receiving a yearly allowance of $80, beginning in 1845, which continued until her death in 1858. [7]

Endnotes:

[1] Penrose, Maryly P., Compendium of Early Mohawk Valley Families, Vol. 1. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1990.

[2] Affidavit by Anna House, wife of Peter C. House, Revolutionary War Pension file of Peter C. House, State of New York, Herkimer County, 4 Oct 1841.

[3] Watt, Gavin K., The Burning of the Valleys; Dundrum Press, Toronto; 1997.

[4] Watt, Gavin K., I am heartily ashamed: Volume II: The Revolutionary War's Final Campaign as Waged from Canada in 1782; Dundurn Publishing.

[5] Old map showing location of A. Rosencrantz home; Herkimer County Historical Society

[6] Will of Peter C. House, dated 26 Jun 1813. State of New York, Montgomery County Surrogate's Court, New Courthouse, Room 50, 58 Broadway, P. O. Box 1500, Fonda, NY 12068-1500. Copy of original transcribed by Lawrence E. House, II, July 2011.

[7] Pension records for Peter C. House

[8] 1800 U. S. Census, Town of Minden, New York

[9] Due to the scarcity of records, it is difficult to identify all members of large families during this time period. The petition for the administration of Anna's estate in 1858 identifies 5 sons (1 deceased) and 4 daughters. Genealogies prepared from other sources by researchers L. H. Shults, Kathleen Fenton and Ross Eckler identify 5 additional children, 3 of whom supposedly died young.

[10] Barone, Constance, Sackets Harbor Site Manager, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

[11] Horton, Gerald, Horton's Historical Articles, http://hortonsarticles.org/hh7thousand.htm ; 10 Jun 2009.

[12] Morris, John D., Sword of the Border: Major Jacob Jennings Brown, 1775-1828.

[13] One generation and first wife: Ken Johnson and Sylvia Novak. Two generations and first wife: L. H. Shults and David Stanley. Two generations and second wife: Roy Francis Howes and Marsha Strong. Howes, Strong and Stanley say Peter's father was killed at Oriskany but Anna's affidavit says Peter's two brothers were killed, not his father.

Compiled by Lawrence E. House, II - 4th great grandson of Peter C. House

Inscription

Erected to the memory of unknown United States soldiers and sailors killed in action or died of wounds in this vicinity during the War of 1812

Gravesite Details

Unidentified Gravesite