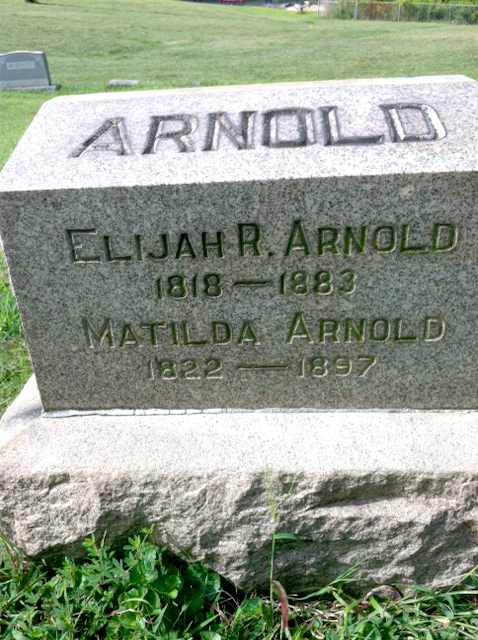

[Correspondence of the Baltimore Sun] ANNAPOLIS, Feb. 20. — Mr. Elijah R. Arnold, a well-known farmer of North Severn, Anne Arundel county, died there at an early hour this morning:, of general debility, aged 62 years. Deceased had held several public positions, having been a justice of the peace, county commissioner, supervisor, assessor, etc. He was also an enrolling officer during the war. One of his sons, John W. Arnold, is a commission merchant of Baltimore, and another, Solon Arnold, is cadet engineer in the navy, on duty in California.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Baltimore Sun

September 13, 1996 | By DAN RODRICKS

Stone marked slaveowner's grave

With the help of the Anne Arundel Genealogical Society, we've learned more about that 165-year-old gravestone discovered last week in some brush along Ritchie Highway in Arnold. Seems the man whose name is inscribed on the stone, Elijah Redmond, was an Arundel landowner (probably a farmer) who had slaves and willed their freedom from his grave, though with conditions.

It's all in court records in Annapolis. Redmond's extensive will was probated in December 1831, the same month he died at age 70, with many prominent early Arundel landowners listed among witnesses. According to Audrey Bagby, president of the genealogical society, Redmond owned land known as "Little Bushey Neck Resurveyed." He left the land to his only surviving child, Rebecca Redmond Arnold, and stipulated that the land later be transferred to her son, Elijah Redmond Arnold. He also left his namesake and grandson $2,000.

But the most interesting part of Redmond's will is his granting of freedom to a slave woman, her three children and two male slaves named Henry and Ben. The female slave, Flora, was granted a portion of the Redmond land and $50. Also freed were her three children -- John, Eliza and Ann. In addition, Redmond stipulated that John be granted $400 at his 21st birthday and Eliza $350 when she turned 16. He made no monetary bequest to Ann. (The ages of the children at the time of Redmond's death are not known.)

While Flora's freedom was granted outright, Henry's and Ben's were granted with conditions. Henry was to be freed after serving 10 more years on the Redmond estate. Ben was to be freed when he turned 30. (It is not known how old the slave Ben was at the time of his master's death.)

The conditions of Elijah Redmond's will follow the trend of the time. Slavery in Maryland was in decline, albeit gradual, in the 1820s and 1830s. Historian Robert J. Brugger notes in his excellent book, "Maryland, A Middle Temperament 1634-1980," that the number of freed blacks in the state grew from 30,000 in 1810 to nearly 50,000 in 1830, the year before Redmond died. Around that time, antislavery meetings were being held in Baltimore and a city newspaper, the Federal Gazette, announced that it would no longer carry the advertisements of slave dealers. In 1826, citizens in Baltimore County petitioned for a state law that would "eventually but gradually and totally extinguish slavery in Maryland."

While antislavery grew in Baltimore and the central part of the state, some slave owners took their property to the south and west. Others, who stayed put, freed their slaves by will or deed, though often with conditions. In that group was Elijah Redmond.

How his gravestone ended up today in some brush near the Big Vanilla Racquet Club -- where it was discovered and reported to This Just In by Jack Milstead of the State Highway Administration -- remains a mystery.

Audrey Bagby says Redmond was probably buried in a family graveyard that disappeared with the passage of time and the development of old farm land in the Arnold area. Such disturbances have been common, she says, and that's why she's active in a group called the Coalition to Protect Maryland Burial Sites.

[Correspondence of the Baltimore Sun] ANNAPOLIS, Feb. 20. — Mr. Elijah R. Arnold, a well-known farmer of North Severn, Anne Arundel county, died there at an early hour this morning:, of general debility, aged 62 years. Deceased had held several public positions, having been a justice of the peace, county commissioner, supervisor, assessor, etc. He was also an enrolling officer during the war. One of his sons, John W. Arnold, is a commission merchant of Baltimore, and another, Solon Arnold, is cadet engineer in the navy, on duty in California.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Baltimore Sun

September 13, 1996 | By DAN RODRICKS

Stone marked slaveowner's grave

With the help of the Anne Arundel Genealogical Society, we've learned more about that 165-year-old gravestone discovered last week in some brush along Ritchie Highway in Arnold. Seems the man whose name is inscribed on the stone, Elijah Redmond, was an Arundel landowner (probably a farmer) who had slaves and willed their freedom from his grave, though with conditions.

It's all in court records in Annapolis. Redmond's extensive will was probated in December 1831, the same month he died at age 70, with many prominent early Arundel landowners listed among witnesses. According to Audrey Bagby, president of the genealogical society, Redmond owned land known as "Little Bushey Neck Resurveyed." He left the land to his only surviving child, Rebecca Redmond Arnold, and stipulated that the land later be transferred to her son, Elijah Redmond Arnold. He also left his namesake and grandson $2,000.

But the most interesting part of Redmond's will is his granting of freedom to a slave woman, her three children and two male slaves named Henry and Ben. The female slave, Flora, was granted a portion of the Redmond land and $50. Also freed were her three children -- John, Eliza and Ann. In addition, Redmond stipulated that John be granted $400 at his 21st birthday and Eliza $350 when she turned 16. He made no monetary bequest to Ann. (The ages of the children at the time of Redmond's death are not known.)

While Flora's freedom was granted outright, Henry's and Ben's were granted with conditions. Henry was to be freed after serving 10 more years on the Redmond estate. Ben was to be freed when he turned 30. (It is not known how old the slave Ben was at the time of his master's death.)

The conditions of Elijah Redmond's will follow the trend of the time. Slavery in Maryland was in decline, albeit gradual, in the 1820s and 1830s. Historian Robert J. Brugger notes in his excellent book, "Maryland, A Middle Temperament 1634-1980," that the number of freed blacks in the state grew from 30,000 in 1810 to nearly 50,000 in 1830, the year before Redmond died. Around that time, antislavery meetings were being held in Baltimore and a city newspaper, the Federal Gazette, announced that it would no longer carry the advertisements of slave dealers. In 1826, citizens in Baltimore County petitioned for a state law that would "eventually but gradually and totally extinguish slavery in Maryland."

While antislavery grew in Baltimore and the central part of the state, some slave owners took their property to the south and west. Others, who stayed put, freed their slaves by will or deed, though often with conditions. In that group was Elijah Redmond.

How his gravestone ended up today in some brush near the Big Vanilla Racquet Club -- where it was discovered and reported to This Just In by Jack Milstead of the State Highway Administration -- remains a mystery.

Audrey Bagby says Redmond was probably buried in a family graveyard that disappeared with the passage of time and the development of old farm land in the Arnold area. Such disturbances have been common, she says, and that's why she's active in a group called the Coalition to Protect Maryland Burial Sites.

Gravesite Details

This is likely a replacement stone or a recent marker added as it appears newer than others of its age. Probably replaced around 1996 per article above?

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement