While their names were known, their bodies for the most part were unrecognizable. And with the exception of one man who was identified and claimed by his family, they were buried together in a single, unmarked grave.

Other graves were dug to the right and left of them, and tombstones lovingly planted to record for posterity who was buried there. Yet, the 39 unclaimed bodies remained with no marker, no message to posterity that they once had lived — and violently died — at the state hospital for the mentally ill. Soon, the very site where they were laid to rest was forgotten.

Now, almost a century later, the grave of "the unfortunates" has been located, and hospital officials say they want to rectify what was a grievous oversight.

"The patients deserve to be named, to have their gravesite noted," said Larry Gross, executive director of what is now known as Griffin Memorial Hospital.

Early-morning fire sweeps through men's wards

The worst fire in the state's history, measured by the number of lives lost, erupted about 3:45 a.m. in or near a linen closet in a residential ward. A steam whistle at the hospital's power plant was used to sound a general alarm, summoning all employees to help with evacuation of two men's wards where the fire had quickly spread.

Early accounts say hand-held chemical extinguishers were used until the city fire department arrived. Norman Deputy Fire Chief Jim Bailey says the department may only have had one pumper truck at the time.

"If a fire like that broke out now, there'd be smoke alarms and a sprinkler system, and the building would be constructed out of fire-resistant material," he said.

Back then, the wooden structures ignited like matchsticks and firefighters had to rely on bucket brigades to augment what was probably a single hose stream from a pumper truck.

Two wards and a cafeteria burned before the fire was extinguished. Some 80 patients on the wards' upper floors were safely evacuated, but 40 died, most of them housed on the first floor, and many of them still in their beds, dead of smoke inhalation, Bailey said.

"It was a terrible tragedy that could have been even worse if the fire had not been contained to those two buildings," Bailey said, noting that the hospital housed up to 1,000 patients at that time.

Curiosity in 1980s spurs search for unmarked grave

As a rookie fireman in the 1980s, Bailey was intrigued by accounts of the fire and the fact that a mass grave existed in the International Order of Odd Fellows Cemetery in east Norman, although no one seemed to know exactly where.

"It seemed to me that a grave for that many people should be marked. It seemed a sad testament to how the mentally ill were treated back then that it was not," he said.

In the early 1900s, mental illness was loosely defined to include mental retardation and epilepsy, as well as psychiatric disorders. Little treatment was available, and the unfortunate victims of these types of illnesses often were confined for life to hospitals that served mainly as human warehouses.

"Peoples' rights weren't protected back then like they are today, and it was relatively easy to get someone hospitalized," Gross said.

Once having heard of the fire, Bailey never lost his curiosity about the mass grave, prompting him in the early 2000s to contact both hospital officials and the Oklahoma Archeological Survey at the University of Oklahoma to see if there was a way to search for the burial site.

"When he first called us, we didn't have the equipment to do anything about it," said Scott Hammerstedt, a member of the survey's research faculty. "But when he contacted us again earlier this year, we believed we could help."

OU had acquired a ground penetrating radar, a geophysical method that uses radar pulses to image the subsurface. Hperbolic reflections can indicate the presence of reflectors buried beneath the surface, showing up on radar as anamolies that could be associated with human burials, Hammerstedt said.

In early January, Hammerstedt and two assistants spent the better part of two days at the IOOF Cemetery, marking off grids and using the radar to search open spaces where it appeared likely bodies could be buried.

On the second day, their search paid off.

Grave located with aid of radar

"Lo and behold, there it was," Gross said, in the northwest corner of the cemetery near the intersection of Porter Avenue and Rock Creek Road.

Without digging below the surface, Hammerstedt said, "you can never be 100 percent sure, but I'm as confident as anyone can be without excavating that we've found where the bodies are buried," Hammerstedt said.

In a 1918 newspaper account of the burial, the bodies were placed in individual coffins and put into one large, 13- by 16-foot grave.

"Every kindly consideration" was given to them, according to an April 15, 1918, story in the Norman Transcript. Although, one consideration was noticeably lacking: a notation in cemetery records of where the grave is located.

Cemetery manager Tim Bowling said records indicate numerous people were buried on the same day on April 14, 1918, but no block and lot number are listed beside the names, something that is standard information for other burials.

"Unfortunately, I think that's how the mentally ill were treated back then," Bowling said.

Memorial planned

Having located the grave, Gross and his staff have undertaken the task of verifying names of the dead and attempting to track down their descendants.

"I feel like we owe them this," Gross said. "These people were in our care at the time they died. It seemed to me not right that we didn't know where they were buried or that their burial site should go unmarked."

One patient whose remains were identifiable was not buried in the mass grave. Ona Havill was claimed by relatives and buried in Independence Cemetery in rural Cleveland County.

Another patient's remains were identified by relatives but his body was included in the mass burial.

"The names of those who died were known, but most were burnt beyond recognition. Each was placed in a separate coffin for the burial that took place within a day of the fire," Gross said.

Because of hospital privacy laws, Gross says he is not free to release the names of the dead, although he is working with legal staff to see if at some point they can be made public.

What he and Bailey envision is a headstone or memorial at the gravesite with the names carved on it.

"If we're successful in tracking down descendants, we would like at some point to have a service, to have a dedication of a memorial," Gross said.

by Jane Glenn Cannon Modified: May 12, 2014 at 2:00 pm • Published: May 11, 2014

While their names were known, their bodies for the most part were unrecognizable. And with the exception of one man who was identified and claimed by his family, they were buried together in a single, unmarked grave.

Other graves were dug to the right and left of them, and tombstones lovingly planted to record for posterity who was buried there. Yet, the 39 unclaimed bodies remained with no marker, no message to posterity that they once had lived — and violently died — at the state hospital for the mentally ill. Soon, the very site where they were laid to rest was forgotten.

Now, almost a century later, the grave of "the unfortunates" has been located, and hospital officials say they want to rectify what was a grievous oversight.

"The patients deserve to be named, to have their gravesite noted," said Larry Gross, executive director of what is now known as Griffin Memorial Hospital.

Early-morning fire sweeps through men's wards

The worst fire in the state's history, measured by the number of lives lost, erupted about 3:45 a.m. in or near a linen closet in a residential ward. A steam whistle at the hospital's power plant was used to sound a general alarm, summoning all employees to help with evacuation of two men's wards where the fire had quickly spread.

Early accounts say hand-held chemical extinguishers were used until the city fire department arrived. Norman Deputy Fire Chief Jim Bailey says the department may only have had one pumper truck at the time.

"If a fire like that broke out now, there'd be smoke alarms and a sprinkler system, and the building would be constructed out of fire-resistant material," he said.

Back then, the wooden structures ignited like matchsticks and firefighters had to rely on bucket brigades to augment what was probably a single hose stream from a pumper truck.

Two wards and a cafeteria burned before the fire was extinguished. Some 80 patients on the wards' upper floors were safely evacuated, but 40 died, most of them housed on the first floor, and many of them still in their beds, dead of smoke inhalation, Bailey said.

"It was a terrible tragedy that could have been even worse if the fire had not been contained to those two buildings," Bailey said, noting that the hospital housed up to 1,000 patients at that time.

Curiosity in 1980s spurs search for unmarked grave

As a rookie fireman in the 1980s, Bailey was intrigued by accounts of the fire and the fact that a mass grave existed in the International Order of Odd Fellows Cemetery in east Norman, although no one seemed to know exactly where.

"It seemed to me that a grave for that many people should be marked. It seemed a sad testament to how the mentally ill were treated back then that it was not," he said.

In the early 1900s, mental illness was loosely defined to include mental retardation and epilepsy, as well as psychiatric disorders. Little treatment was available, and the unfortunate victims of these types of illnesses often were confined for life to hospitals that served mainly as human warehouses.

"Peoples' rights weren't protected back then like they are today, and it was relatively easy to get someone hospitalized," Gross said.

Once having heard of the fire, Bailey never lost his curiosity about the mass grave, prompting him in the early 2000s to contact both hospital officials and the Oklahoma Archeological Survey at the University of Oklahoma to see if there was a way to search for the burial site.

"When he first called us, we didn't have the equipment to do anything about it," said Scott Hammerstedt, a member of the survey's research faculty. "But when he contacted us again earlier this year, we believed we could help."

OU had acquired a ground penetrating radar, a geophysical method that uses radar pulses to image the subsurface. Hperbolic reflections can indicate the presence of reflectors buried beneath the surface, showing up on radar as anamolies that could be associated with human burials, Hammerstedt said.

In early January, Hammerstedt and two assistants spent the better part of two days at the IOOF Cemetery, marking off grids and using the radar to search open spaces where it appeared likely bodies could be buried.

On the second day, their search paid off.

Grave located with aid of radar

"Lo and behold, there it was," Gross said, in the northwest corner of the cemetery near the intersection of Porter Avenue and Rock Creek Road.

Without digging below the surface, Hammerstedt said, "you can never be 100 percent sure, but I'm as confident as anyone can be without excavating that we've found where the bodies are buried," Hammerstedt said.

In a 1918 newspaper account of the burial, the bodies were placed in individual coffins and put into one large, 13- by 16-foot grave.

"Every kindly consideration" was given to them, according to an April 15, 1918, story in the Norman Transcript. Although, one consideration was noticeably lacking: a notation in cemetery records of where the grave is located.

Cemetery manager Tim Bowling said records indicate numerous people were buried on the same day on April 14, 1918, but no block and lot number are listed beside the names, something that is standard information for other burials.

"Unfortunately, I think that's how the mentally ill were treated back then," Bowling said.

Memorial planned

Having located the grave, Gross and his staff have undertaken the task of verifying names of the dead and attempting to track down their descendants.

"I feel like we owe them this," Gross said. "These people were in our care at the time they died. It seemed to me not right that we didn't know where they were buried or that their burial site should go unmarked."

One patient whose remains were identifiable was not buried in the mass grave. Ona Havill was claimed by relatives and buried in Independence Cemetery in rural Cleveland County.

Another patient's remains were identified by relatives but his body was included in the mass burial.

"The names of those who died were known, but most were burnt beyond recognition. Each was placed in a separate coffin for the burial that took place within a day of the fire," Gross said.

Because of hospital privacy laws, Gross says he is not free to release the names of the dead, although he is working with legal staff to see if at some point they can be made public.

What he and Bailey envision is a headstone or memorial at the gravesite with the names carved on it.

"If we're successful in tracking down descendants, we would like at some point to have a service, to have a dedication of a memorial," Gross said.

by Jane Glenn Cannon Modified: May 12, 2014 at 2:00 pm • Published: May 11, 2014

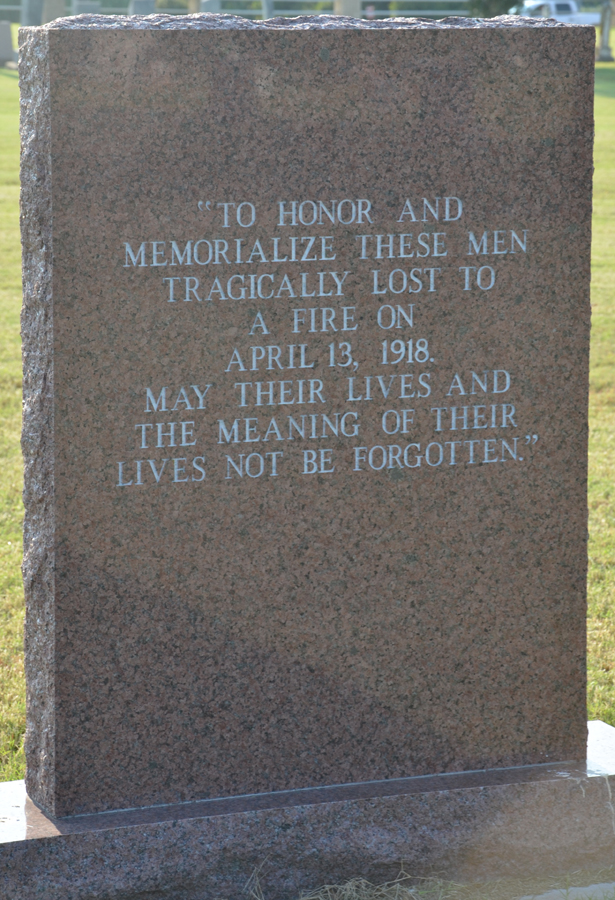

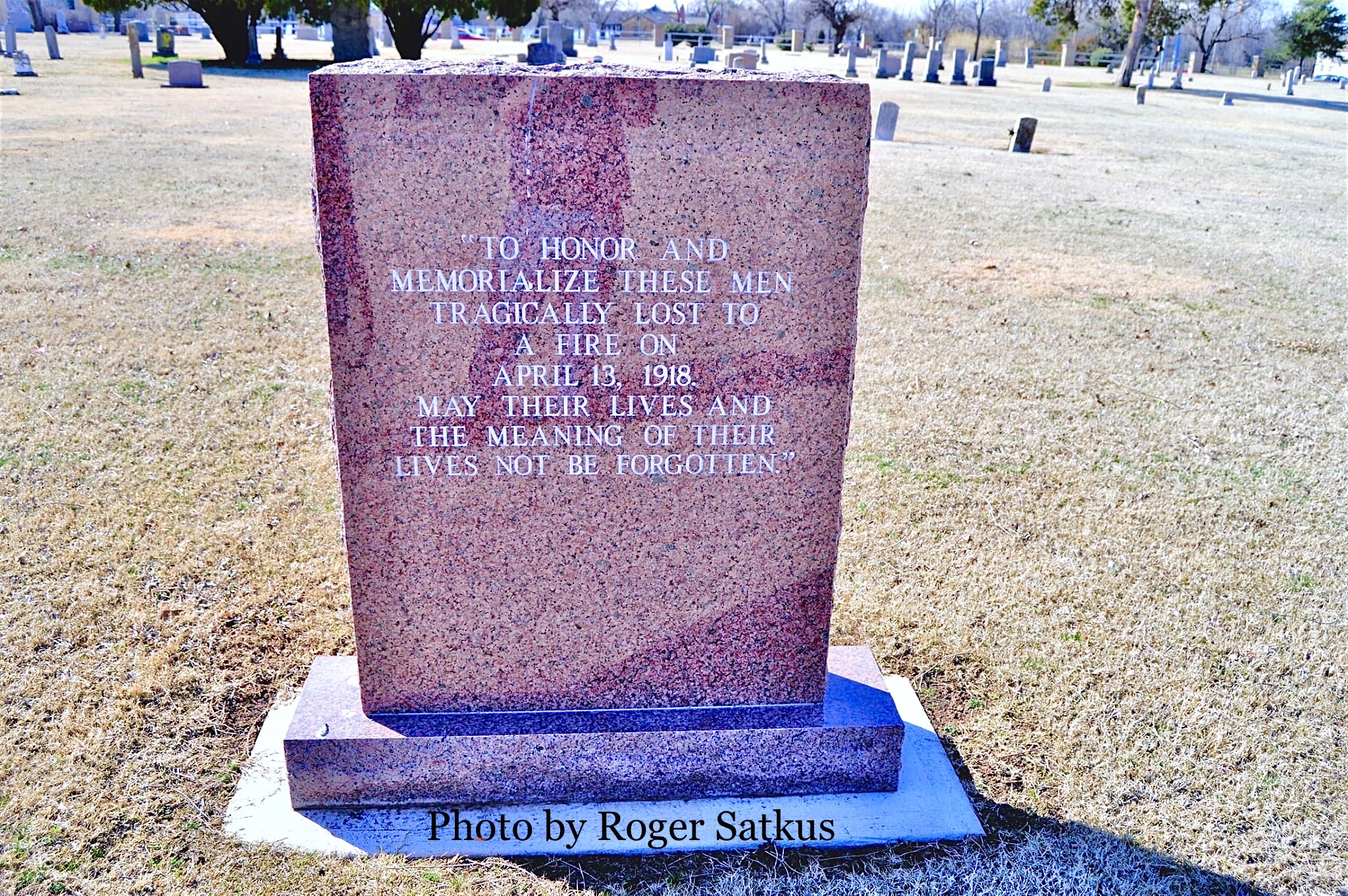

Inscription

To honor and memorialize these men tragically lost to a fire on April 13, 1918. May their lives and the meaning of their lives not be forgotten.

Gravesite Details

no stone

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement