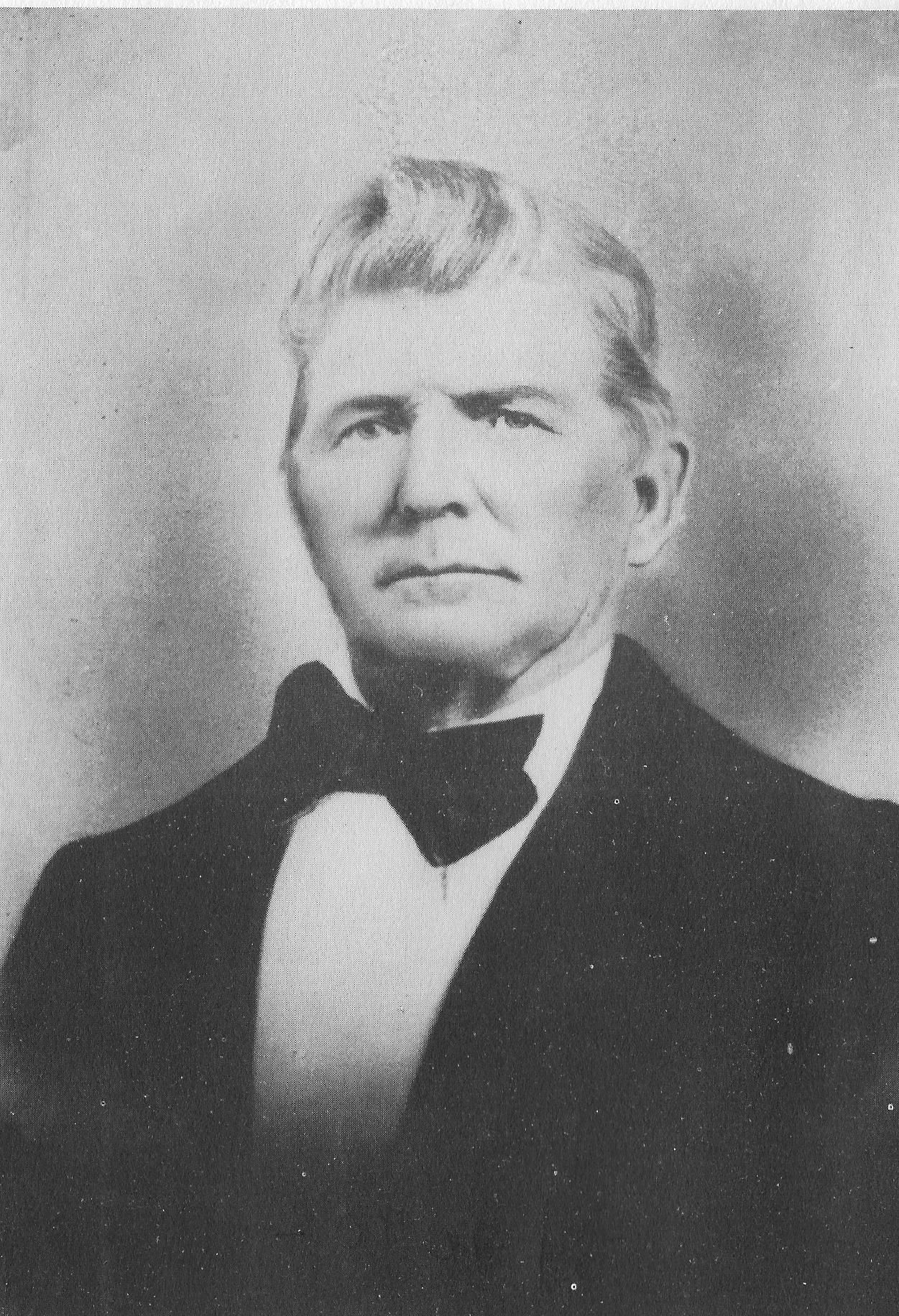

Born in 1812 in Kaskaskia, Illinois Territory, Lee had a tumultuous childhood. At age three, his mother died after years of lingering illnesses, leaving Lee to his alcoholic father. From age seven to sixteen Lee was raised in an uncle's family. He worked for a time as a mail carrier before assuming managerial responsibility for his uncle's farm, then worked several years as a store clerk in Galena, Illinois. Finally, Lee moved to Vandalia, Illinois, where he met and married Agatha Ann Woolsey in 1833.

It was in Vandalia that Lee and his wife encountered Mormonism. In 1837 a Mormon missionary converted the couple to the young religion, which had been formally organized only seven years before. Lee's religious passion quickly became the driving force in his life, prompting him to move in 1838 to a homestead near the Mormon town of Far West, Missouri.

The large influx of Mormons into Northwest Missouri caused enormous tensions with the non-Mormon ("gentile") population. Individual confrontations soon exploded into near warfare involving murder, destruction of property, and cycles of raids and counter-raids between the Mormons and gentiles. Lee played an active role in many of the military conflicts, and soon became a member of the Danite Band, the formally organized Mormon militia. Finally Missouri's governor ordered the Mormons expelled or exterminated.

As the Mormons began preparing for their trek eastward to Nauvoo, Illinois, Lee's religious devotion continued to strengthen. In 1838 he was promoted within the priesthood and made a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy. From 1839 to 1844 he spent much of his time winning converts in Illinois, Tennessee and Kentucky. In 1843 he was chosen to guard the home of the church's founder and prophet, Joseph Smith.

John Lee's religious fervor only grew in intensity as the young religion entered its darkest hour. In June 1844 a mob dragged Joseph Smith and his brother from their jail cell in Carthage, Illinois, and murdered them, causing a crisis of leadership within the church. In addition, there was internal dissension over the doctrine of plural marriage, which had been formally announced within the church in 1843. Lee accepted the new doctrine, soon taking five more wives, and he remained devotedly loyal to the church leadership, especially the new leader, Brigham Young, whom Lee assisted during the Mormon flight to the "Winter Quarters."

By 1846 the Mormons, decided to seek their own Zion in the American West. By 1847 the first wagons began arriving in Utah's Salt Lake valley. Lee joined the gathering masses of Zion in Utah.

For the next decade, Lee played an important role in expanding the Mormon refuge in the West. He became a prosperous farmer and businessman in Southwestern Utah, helping to establish communal mining, milling and manufacturing complexes. He became the local bishop and the Indian agent to the nearby Paiute Indians. And he continued to be a frequent visitor and trusted confidant of the church leadership in Salt Lake City.

Even in the far West, however, neither Lee nor his co-religionists were beyond the reach of the country whose persecution they had fled. In 1857, prompted by complaints about church power in the territory and a public outcry against polygamy, the United States sent an army to Utah, raising Mormon fears that the final annihilation was at hand. This invasion was the backdrop for the still-controversial Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which a wagon train of about 120 gentile immigrants, suspected of hostility toward the church, was destroyed by Mormon and Paiute forces in southwestern Utah.

Lee's involvement in the massacre -- the extent of which is still vigorously disputed and will probably never be known -- was to haunt him for the next two decades, and would ultimately lead to his execution. In 1858 a federal judge came to southwestern Utah to investigate the massacre and Lee's part in it, but Lee went into hiding and local Mormons refused to cooperate with the investigation. Folk songs dating back to this year blamed Lee for the massacre.

Although the church sought to lower Lee's profile, by removing him as a probate judge, the Mormon leadership continued to return his immense loyalty. In 1860, Brigham Young visited one of Lee's mansions and publicly praised his personal industriousness and communal economic contributions. In 1861 the residents of Harmony, Utah, elected him as their presiding elder.

But Lee could not escape the legacy of Mountain Meadows. In 1870 a Utah paper openly condemned Brigham Young for covering up the massacre. That same year Young exiled Lee to a remote part of northern Arizona and excommunicated him from the church.

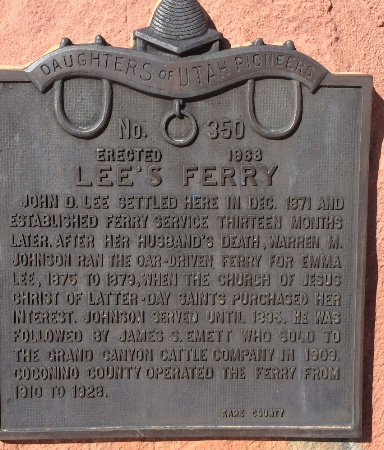

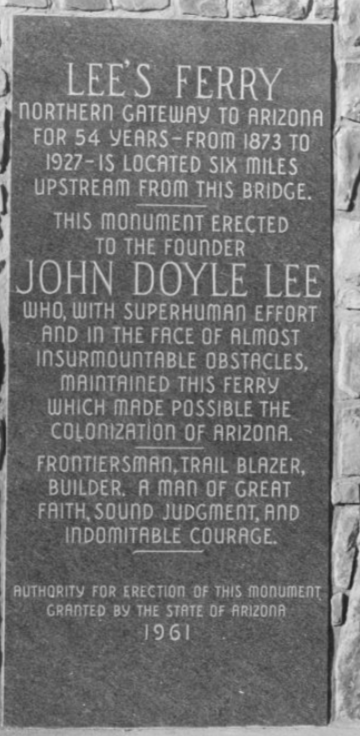

The next several years brought a continued decline in Lee's fortunes. He had several episodes of severe illness; drought followed by torrential rains destroyed many of his buildings and crops; former neighbors preyed upon his livestock and otherwise took advantage of his absence; several of his wives deserted him. Nevertheless, he was managing to eke out a living in a homesteader's cabin near the Colorado River in Northern Arizona (at one point hosting John Wesley Powell's 1869 expedition before their trip through the Grand Canyon) when a sheriff captured him in November 1874.

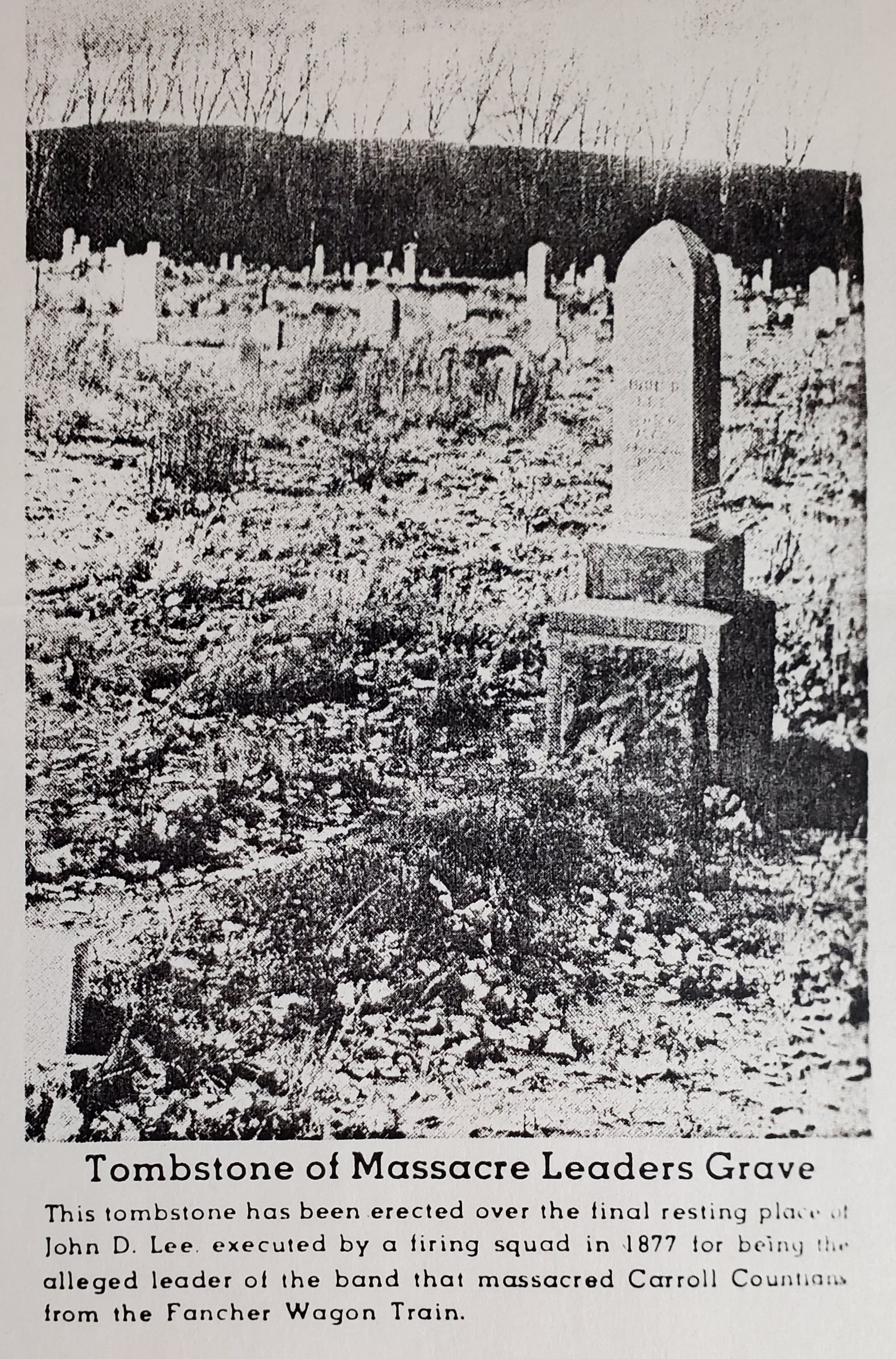

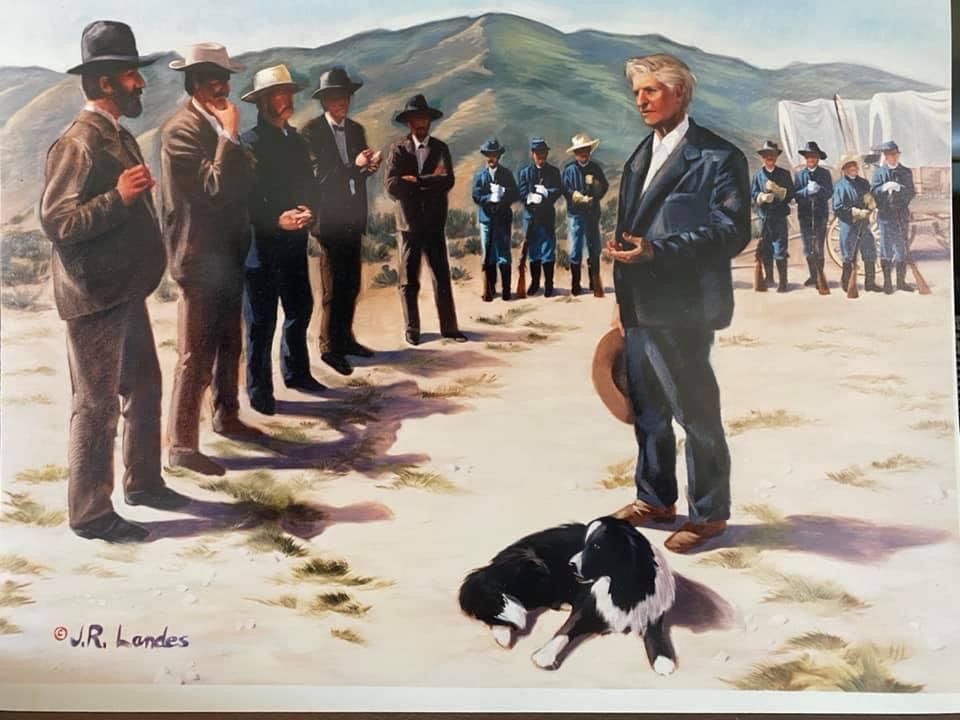

Lee's first trial ended inconclusively with a hung jury. A second trial, in which the prosecution placed the blame squarely on Lee's shoulders, ended with his conviction. The trials were the subject of enormous public attention and gave rise to many accounts of the massacre and of Lee's life. Lee himself continued to profess his innocence. Nearly twenty years after the massacre, Lee was executed at Mountain Meadows.

(PBS-The West Film Project, 2001)

Born in 1812 in Kaskaskia, Illinois Territory, Lee had a tumultuous childhood. At age three, his mother died after years of lingering illnesses, leaving Lee to his alcoholic father. From age seven to sixteen Lee was raised in an uncle's family. He worked for a time as a mail carrier before assuming managerial responsibility for his uncle's farm, then worked several years as a store clerk in Galena, Illinois. Finally, Lee moved to Vandalia, Illinois, where he met and married Agatha Ann Woolsey in 1833.

It was in Vandalia that Lee and his wife encountered Mormonism. In 1837 a Mormon missionary converted the couple to the young religion, which had been formally organized only seven years before. Lee's religious passion quickly became the driving force in his life, prompting him to move in 1838 to a homestead near the Mormon town of Far West, Missouri.

The large influx of Mormons into Northwest Missouri caused enormous tensions with the non-Mormon ("gentile") population. Individual confrontations soon exploded into near warfare involving murder, destruction of property, and cycles of raids and counter-raids between the Mormons and gentiles. Lee played an active role in many of the military conflicts, and soon became a member of the Danite Band, the formally organized Mormon militia. Finally Missouri's governor ordered the Mormons expelled or exterminated.

As the Mormons began preparing for their trek eastward to Nauvoo, Illinois, Lee's religious devotion continued to strengthen. In 1838 he was promoted within the priesthood and made a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy. From 1839 to 1844 he spent much of his time winning converts in Illinois, Tennessee and Kentucky. In 1843 he was chosen to guard the home of the church's founder and prophet, Joseph Smith.

John Lee's religious fervor only grew in intensity as the young religion entered its darkest hour. In June 1844 a mob dragged Joseph Smith and his brother from their jail cell in Carthage, Illinois, and murdered them, causing a crisis of leadership within the church. In addition, there was internal dissension over the doctrine of plural marriage, which had been formally announced within the church in 1843. Lee accepted the new doctrine, soon taking five more wives, and he remained devotedly loyal to the church leadership, especially the new leader, Brigham Young, whom Lee assisted during the Mormon flight to the "Winter Quarters."

By 1846 the Mormons, decided to seek their own Zion in the American West. By 1847 the first wagons began arriving in Utah's Salt Lake valley. Lee joined the gathering masses of Zion in Utah.

For the next decade, Lee played an important role in expanding the Mormon refuge in the West. He became a prosperous farmer and businessman in Southwestern Utah, helping to establish communal mining, milling and manufacturing complexes. He became the local bishop and the Indian agent to the nearby Paiute Indians. And he continued to be a frequent visitor and trusted confidant of the church leadership in Salt Lake City.

Even in the far West, however, neither Lee nor his co-religionists were beyond the reach of the country whose persecution they had fled. In 1857, prompted by complaints about church power in the territory and a public outcry against polygamy, the United States sent an army to Utah, raising Mormon fears that the final annihilation was at hand. This invasion was the backdrop for the still-controversial Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which a wagon train of about 120 gentile immigrants, suspected of hostility toward the church, was destroyed by Mormon and Paiute forces in southwestern Utah.

Lee's involvement in the massacre -- the extent of which is still vigorously disputed and will probably never be known -- was to haunt him for the next two decades, and would ultimately lead to his execution. In 1858 a federal judge came to southwestern Utah to investigate the massacre and Lee's part in it, but Lee went into hiding and local Mormons refused to cooperate with the investigation. Folk songs dating back to this year blamed Lee for the massacre.

Although the church sought to lower Lee's profile, by removing him as a probate judge, the Mormon leadership continued to return his immense loyalty. In 1860, Brigham Young visited one of Lee's mansions and publicly praised his personal industriousness and communal economic contributions. In 1861 the residents of Harmony, Utah, elected him as their presiding elder.

But Lee could not escape the legacy of Mountain Meadows. In 1870 a Utah paper openly condemned Brigham Young for covering up the massacre. That same year Young exiled Lee to a remote part of northern Arizona and excommunicated him from the church.

The next several years brought a continued decline in Lee's fortunes. He had several episodes of severe illness; drought followed by torrential rains destroyed many of his buildings and crops; former neighbors preyed upon his livestock and otherwise took advantage of his absence; several of his wives deserted him. Nevertheless, he was managing to eke out a living in a homesteader's cabin near the Colorado River in Northern Arizona (at one point hosting John Wesley Powell's 1869 expedition before their trip through the Grand Canyon) when a sheriff captured him in November 1874.

Lee's first trial ended inconclusively with a hung jury. A second trial, in which the prosecution placed the blame squarely on Lee's shoulders, ended with his conviction. The trials were the subject of enormous public attention and gave rise to many accounts of the massacre and of Lee's life. Lee himself continued to profess his innocence. Nearly twenty years after the massacre, Lee was executed at Mountain Meadows.

(PBS-The West Film Project, 2001)

Family Members

-

![]()

Agatha Ann Woolsey Lee

1814–1866 (m. 1833)

-

![]()

Nancy Bean Decker

1826–1903 (m. 1844)

-

![]()

Louisa Free Wells

1824–1886 (m. 1845)

-

![]()

Sarah Caroline Williams Young

1830–1907 (m. 1845)

-

![]()

Martha Elizabeth Berry Dorrity

1827–1885 (m. 1846)

-

![]()

Mary Ann Workman Bennett

1829–1904 (m. 1846)

-

![]()

Nancy Gibbons Armstrong

1799–1847 (m. 1847)

-

![]()

Lovina Young Lee

1820–1884 (m. 1847)

-

![]()

Mary Vance "Polly" Young Lee

1817–1890 (m. 1847)

-

![]()

Rachel Andora Woolsey Lee

1825–1912 (m. 1851)

-

![]()

Mary Leah Groves Matthews

1836–1912 (m. 1852)

-

![]()

Mary Ann Williams Lee

1844–1882 (m. 1857)

-

![]()

Emma Batchelor French

1836–1897 (m. 1858)

-

![]()

Terressa Morse Phelps

1813–1882 (m. 1859)

-

![]()

Ann "Annie" Gordge Kenney

1849–1923 (m. 1864)

-

![]()

Sarah Jane Lee Underwood

1838–1915

-

![]()

John Alma Lee

1840–1881

-

![]()

Mary Adeline Lee Darrow

1841–1924

-

![]()

Joseph Hyrum Lee

1844–1932

-

John Heber Lee

1846–1847

-

John Brigham Lee

1846–1856

-

![]()

Cornelia Lee Decker Mortensen

1846–1937

-

![]()

John Willard Lee

1849–1923

-

![]()

Harriet Josephine Lee Bliss

1850–1922

-

![]()

Nancy Emily Lee Dalton

1850–1930

-

![]()

Louisa Evelyn Lee Prince

1850–1932

-

![]()

Elizabeth Lee Pace

1851–1912

-

![]()

John David Lee

1851–1922

-

William Orson Lee

1852–1908

-

![]()

Ellen S Lee Clark

1852–1924

-

![]()

Harvey Parley Lee

1852–1927

-

![]()

James Young Lee

1852–1939

-

![]()

Helen Rachel "Nellie" Lee Stocks

1852–1943

-

![]()

Samuel Gully Lee

1853–1896

-

![]()

Armelia Lee

1854–1860

-

![]()

Erastus Franklin Lee

1854–1914

-

![]()

George Albert Lee

1855–1862

-

![]()

George Albert Lee

1855–1862

-

![]()

Thirza Jane Lee Anderson

1855–1894

-

![]()

Melvina Young Lee Clark

1856–1920

-

![]()

Mariam Leah Lee Cornelius

1856–1942

-

![]()

Rachael Amorah Lee Smithson

1856–1945

-

![]()

Margaret A Ann Lee

1857–1862

-

![]()

Margaret Ann Lee

1857–1862

-

![]()

Ezra Taft Lee

1857–1925

-

Henrietta Lee

1858–1860

-

![]()

Lucy Olive Lee Maloney

1858–1922

-

![]()

Rachel Olive Lee Norton

1858–1924

-

![]()

John Henry Lee

1859–1859

-

![]()

William James Lee

1860–1920

-

![]()

Sarah Ann Lee Young

1860–1920

-

![]()

John Hurd Lee

1860–1938

-

![]()

John Amasa Lee

1860–1939

-

![]()

Elisha Squire Lee

1862–1937

-

![]()

Charles William Lee

1862–1941

-

![]()

William Franklin Lee

1862–1946

-

Isaac L. "Ike" Lee

1863–1892

-

![]()

Mary Elizabeth Lee Lamb

1864–1941

-

![]()

Mary Serepta Lee Bliss

1865–1897

-

Samuel James Lee

1865–1937

-

![]()

Josephine Helen Lee Jorgensen

1865–1947

-

![]()

Robert Edmond Lee Sr

1866–1928

-

Rachel Emma Lee

1866 – unknown

-

![]()

Jacob Lee

1867–1947

-

Joseph Willard Brigham ""Brig"" Lee

1868–1916

-

![]()

Merab Emma ""Belle"" Lee Morris

1868–1945

-

![]()

Walter Brigham Lee

1869–1939

-

Frances Dell Lee

1872–1888

-

![]()

Albert Doyle Lee

1872–1921

-

![]()

Ammon Doyle Lee

1872–1940

-

![]()

Victoria Elizabeth Lee

1873–1888