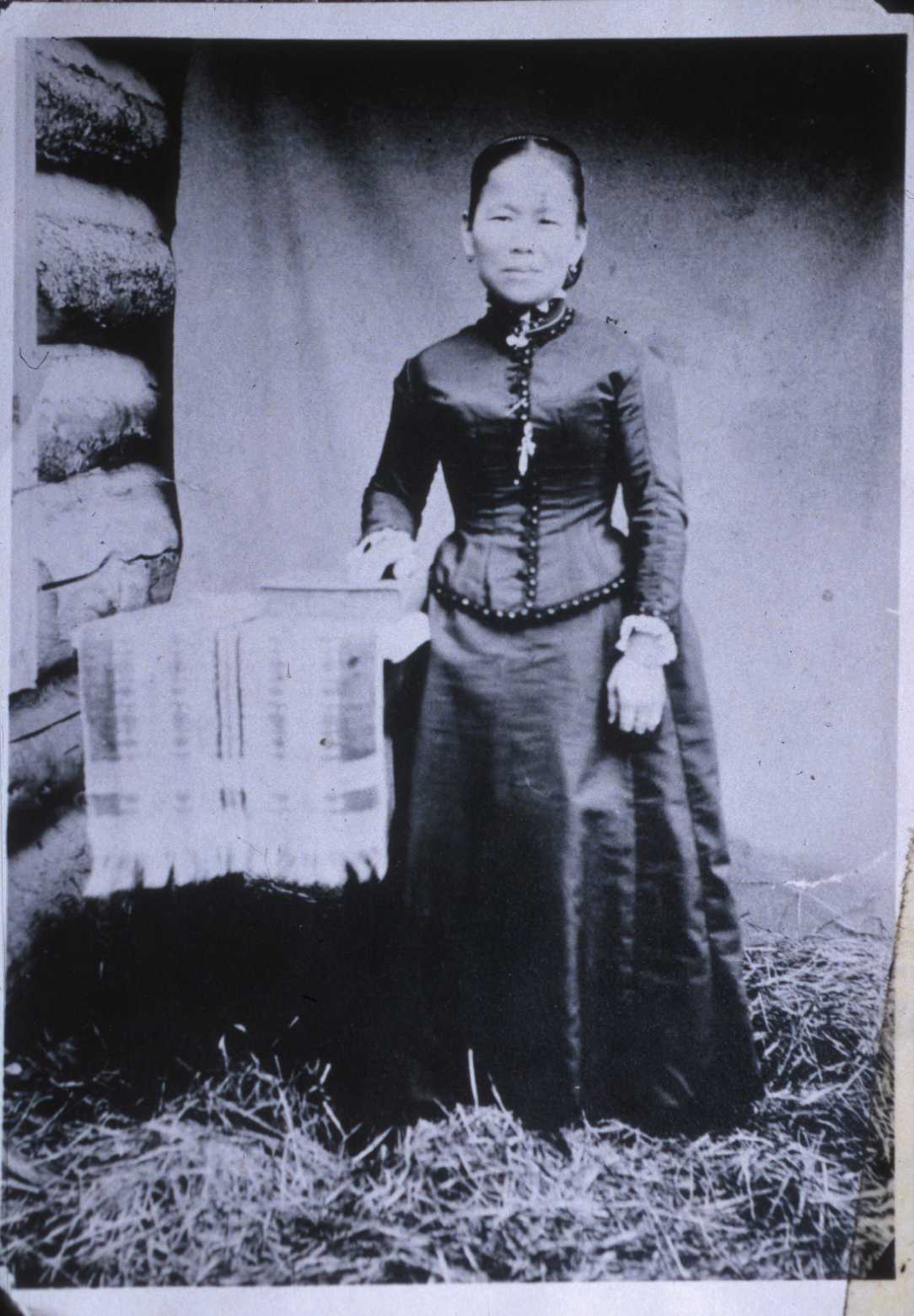

Lula "Polly" was the daughter of impoverished Northern Chinese farmers. Her feet had been bound, then unbound. At 18, she was sold for crop seed and sent to Shanghai, before being exported to America.

She was brought to San Francisco, then to Warrens, Idaho by her "owner" after hearing about a gold rush there.

She met Charles Bemis, a saloon owner, in Warrens. She was introduced to him as "Polly". He was able to defend her from the unwanted advances in the saloon. They married on 13 August 1894 in Warrens.

They relocated 17 miles away to Bemis Point, a farming and hospitality ranch on the Salmon River. After Charles's death in 1923, she remained there in solitude until her death in 1933.

Her body was exhumed and returned to her home, where she is in her final resting place.

=====

A beacon of hope

Though only four-foot-five, nobody held Polly Bemis down.

Polly Bemis was only 4-foot-5 tall, from China, had her feet bound as a child, was sold by her father for two bags of seed, and then smuggled to Portland, Ore., and sold as a slave for $2,500.

She ran a mining town saloon and boarding house in Warren, Idaho, had a pet cougar and made a legend of herself in her own time.

She died in 1933, but even today historians debate whether she was ever a concubine or prostitute, while she denied to the end the story that she was won in a poker game.

China has never been an easy place to live for the masses, and so it was in 1853 when Polly was born in Taishan, Guangdong, in northern China.

Her Chinese name was Lalu Nathoy, and she was selected by her parents to be the daughter whose feet would be bound from childhood so that she could be betrothed to a wealthy man and never have to work - unlike her sisters.

It was a hideous practice, first introduced in Imperial China in the 10th or 11th century, supposedly to make the women more erotic. Binding kept the feet small and curved and tucked under like "golden lotuses," but it was torturous for the children. Only wealthy families could do this; poor families needed every family member to work.

As it turned out, Polly was luckier than most. Her family apparently needed her labor in the fields before they sold her, so she was released from having her feet bound, but it left her walking with "a peculiar rolling gait" the rest of her life.

Much of the American West was developed with laborers from China who planned to make enough money in the U.S. to lift their families in China out of poverty. Mainly they did backbreaking work helping to build the transcontinental railway. Sadly, they were treated harshly and paid low wages.

Customarily, a married Chinese man coming to America would leave his wife behind to care for his parents. Having multiple wives or acquiring concubines was an acceptable practice, thus opening the market for trafficking of Chinese women to America.

After the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, most of the Chinese switched to mining and other endeavors.

In Idaho, many Chinese moved into abandoned gold mining areas after the mining played out, to glean for whatever gold remained. That was the condition of Warren (then called Warrens) when Polly arrived from Portland by boat and pack train on July 8, 1872, at age 18.

Polly's new master in Warren was a wealthy Chinese saloon keeper, whose exact relationship with his young ward remains unclear - even years later after having articles, books and a 1981 movie (Thousand Pieces of Gold) made about her life. He called her Polly, but his name remains unknown (maybe Hong King).

Idaho would be Polly's home for the next 60 years.

Her first challenge would be to learn English. Being from Mandarin-speaking northern China, she could not even speak to the other Chinese, who mostly from the south spoke Cantonese or other dialects. All Chinese writing was mostly the same, but Polly couldn't write.

Later, she somehow managed to get away from her owner and ended up with local saloon keeper Charlie Bemis who had befriended her since she arrived. Polly ran his popular boarding house for him and was his housekeeper. Legend says Charlie won her in a poker game with her Chinese owner, but she always denied it.

In 1890, a sore loser in a poker game shot Charlie in the cheek. The doctor predicted he would die, but he survived after Polly cleaned his wound with a crochet hook and treated it with herbs, cutting the bullet out of his neck with a razor.

Four years later, Polly and Charlie married.

Because she was brought to America illegally, deportation remained a constant threat hanging over Polly's head - until she married Charlie.

Interracial marriages were against the law in those days in many states, but in Idaho, it only applied between Caucasians and African-Americans. In 1921, "Mongolians" was added to the prohibited list, but by then, Polly and Charlie had been married 27 years.

Polly had a happy personality, was petite, pretty, and witty - which made her popular with everyone. She learned western cooking, adopted Western ways, and loved children and animals.

She could also be tough. When one diner complained about the coffee, she pulled out a butcher's knife and challenged him to repeat his complaint. The coffee was just fine.

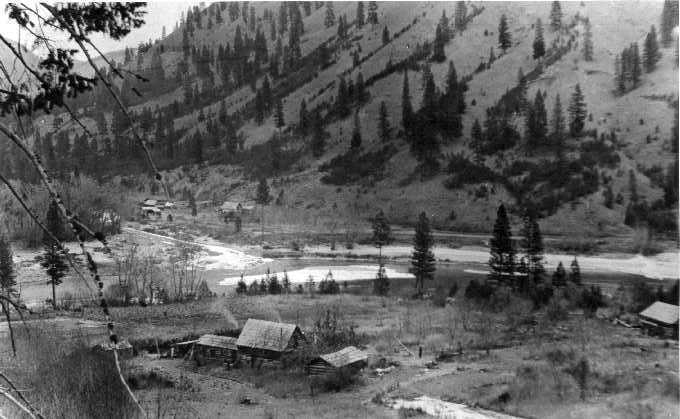

Polly and Charlie built a two-story homestead for themselves 17 miles from town in a deep canyon on the Salmon River - also called the River of No Return because it was only navigable in one direction.

Their neighbors were two German miners - Peter Klinkhammer and Charlie Shepp - who mined gold claims in the hills.

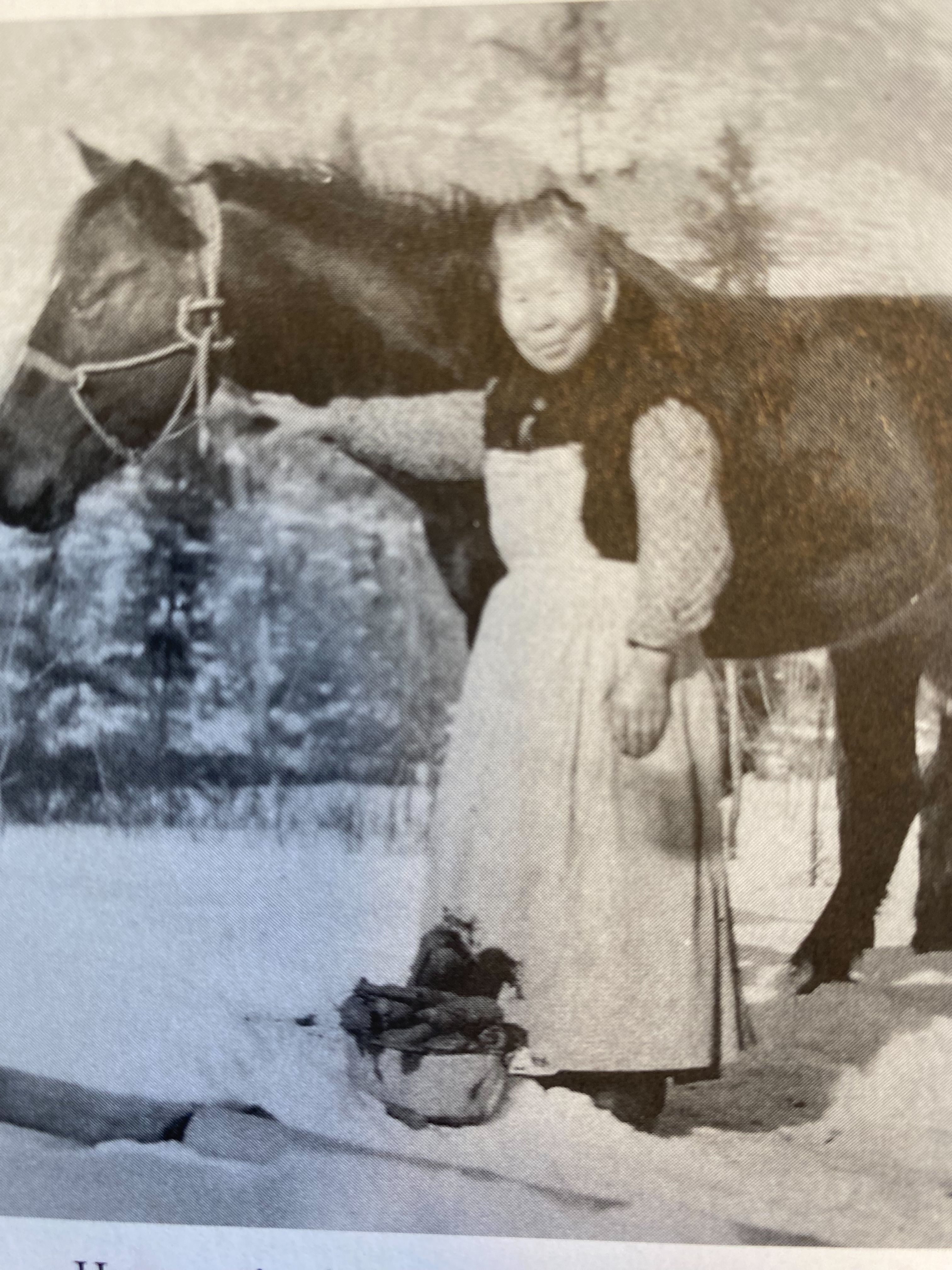

Polly and Charlie Bemis were quite different. Charlie was lazy, liked to play his fiddle and gamble, while the industrious Polly would tend the garden and orchard, take care of the cows, horses, cat, dog, chickens and pet cougar, crochet and sew, and preserve vegetables and fruit to sell. She also became an excellent fisherman, once catching 27 fish in one day.

For years she stayed home running the ranch, while Charlie would ride to town to sell their products and check on his saloon.

By 1919, Charlie was bedridden and Polly had to care for him. If she needed help, she'd hang a towel upon a bush and one of the Germans would rush over. Eventually, a battery-powered phone line replaced the towel.

When phonographs and radios were invented, Polly was enthralled. No longer were they living out in the wilderness in isolation. She loved listening to Cal Stewart's funny monologues. Her favorite was "Uncle Josh in a Chinese Laundry."

Because Polly was an interesting character with an interesting story, magazine articles began to appear about the unusual couple. Soon tourists would drop in to meet them and enjoy their hospitality. She would also take in miners who were ill or injured and nurse them back to health. She was becoming a legend.

An article in Field and Stream magazine by famed publisher Eleanor "Cissy" Patterson - written under her former married name Countess Eleanor Gizycka - described Polly as "neat as a pin, wrinkled as a walnut, and at 67 she is full of dash and charm."

By the 1920s, life was closing in on the aging couple: The house burned down and they moved across the river to stay with their German neighbors.

On Oct. 29, 1922, Charlie died of a lung ailment. Polly moved back to Warren, where childless herself, she took in six-year-old Gay Carrey so the girl could attend school in town.

Neighbor Pete Klinkhammer said the Bemises had "a marriage of convenience." Charlie needed Polly to take care of him, and Polly needed the marriage to prevent her from being deported back to China.

In the ensuing years after Charlie died, Polly's life opened up a bit. She took her first automobile ride, saw her first train, and watched her first movie in Grangeville. She also visited Boise, seeing her first streetcar, tall building, and rode in her first elevator.

In 1924, Polly Bemis returned to the canyon to live in a cabin Klinkhammer and Shepp built for her. In the summer of 1933, she fell ill and was taken to Grangeville, strapped to the back of a horse. She died of a stroke in a nursing home on Nov. 6.

She was buried in the Grangeville Cemetery.

In 1980, Polly was reburied on her beloved ranch; the cabin now restored and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At a time when the Chinese were being vilified in America, Polly Bemis stood out as a beacon of hope for future generations.

The diminutive peasant woman who was sold as a slave but eventually lived in freedom and became a giant personality in her remote little Idaho community made the "melting pot" work for her.

The Salmon was Polly's "river of no return." She never saw China again, but instead became a glittering chapter in the history of a growing multicultural America.

Syd Albright is a writer/journalist/biographer living in Post Falls. He is chairman of the Kootenai County Historic Preservation Commission.

===

Miscegenation laws in America ...

Laws prohibiting marriages between races were not repealed in the U.S. until 1959. Military authorities, in particular, labored under those laws during the World War II and Korean War conflicts when American military personnel sought to marry Asian women. Asian immigrants were not even allowed to become naturalized American citizens until 1943 - 10 years after Polly Bemis died.

===

'Uncle Josh in a Chinese Laundry ...'

Polly Bemis didn't have a problem with political correctness. She loved to listen to a recording of comedian Cal Stewart's character Uncle Josh brawling with a Chinese laundry owner who wouldn't give him his clothes without the claim ticket:

"In less 'n a minnit we wuz a rollin' round on the floor; fust I wuz on top, and then Mr. Hop Soon wuz on top, and you couldn't hav told which one of us the pig tail belonged to. We upset the stove and kicked out the winder, and I sot Mr. Hop Soon in the washtub, and when I got out of thar I had somebody's washin' in one hand and about five yards of that pig tail in tother, and Mr. Hop Soon, he wuz standin' thar yellin' - ung wa moo ye song ki le yung noy song oowe polecee, polecee, polecee.

I had quite a time with that heathen critter."

republished with permission from Syd Albright 8/14/2015

===============================================

Changes to her name are attributed to the latest biography about her by Dr. Priscilla Wegars, entitled "Polly Bemis: The Life and Times of a Chinese American Pioneer".

In 1987, Polly was exhumed in Grangeville and her remains were brought back to her Salmon River home.

Contributor: Lee Loo (50331449)

=====

Also, Dr. Wegars also mentions that Polly was not from Guangdong. She suspects she is from northern China, around the Inner Mongolia area.

The book references interviews where Polly says that she was from the north and brought out of China via Shanghai. She did not speak Cantonese when she arrived in the US, further proving her origin as outside of southern China.

Contributor: Lee Loo (50331449)

Lula "Polly" was the daughter of impoverished Northern Chinese farmers. Her feet had been bound, then unbound. At 18, she was sold for crop seed and sent to Shanghai, before being exported to America.

She was brought to San Francisco, then to Warrens, Idaho by her "owner" after hearing about a gold rush there.

She met Charles Bemis, a saloon owner, in Warrens. She was introduced to him as "Polly". He was able to defend her from the unwanted advances in the saloon. They married on 13 August 1894 in Warrens.

They relocated 17 miles away to Bemis Point, a farming and hospitality ranch on the Salmon River. After Charles's death in 1923, she remained there in solitude until her death in 1933.

Her body was exhumed and returned to her home, where she is in her final resting place.

=====

A beacon of hope

Though only four-foot-five, nobody held Polly Bemis down.

Polly Bemis was only 4-foot-5 tall, from China, had her feet bound as a child, was sold by her father for two bags of seed, and then smuggled to Portland, Ore., and sold as a slave for $2,500.

She ran a mining town saloon and boarding house in Warren, Idaho, had a pet cougar and made a legend of herself in her own time.

She died in 1933, but even today historians debate whether she was ever a concubine or prostitute, while she denied to the end the story that she was won in a poker game.

China has never been an easy place to live for the masses, and so it was in 1853 when Polly was born in Taishan, Guangdong, in northern China.

Her Chinese name was Lalu Nathoy, and she was selected by her parents to be the daughter whose feet would be bound from childhood so that she could be betrothed to a wealthy man and never have to work - unlike her sisters.

It was a hideous practice, first introduced in Imperial China in the 10th or 11th century, supposedly to make the women more erotic. Binding kept the feet small and curved and tucked under like "golden lotuses," but it was torturous for the children. Only wealthy families could do this; poor families needed every family member to work.

As it turned out, Polly was luckier than most. Her family apparently needed her labor in the fields before they sold her, so she was released from having her feet bound, but it left her walking with "a peculiar rolling gait" the rest of her life.

Much of the American West was developed with laborers from China who planned to make enough money in the U.S. to lift their families in China out of poverty. Mainly they did backbreaking work helping to build the transcontinental railway. Sadly, they were treated harshly and paid low wages.

Customarily, a married Chinese man coming to America would leave his wife behind to care for his parents. Having multiple wives or acquiring concubines was an acceptable practice, thus opening the market for trafficking of Chinese women to America.

After the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, most of the Chinese switched to mining and other endeavors.

In Idaho, many Chinese moved into abandoned gold mining areas after the mining played out, to glean for whatever gold remained. That was the condition of Warren (then called Warrens) when Polly arrived from Portland by boat and pack train on July 8, 1872, at age 18.

Polly's new master in Warren was a wealthy Chinese saloon keeper, whose exact relationship with his young ward remains unclear - even years later after having articles, books and a 1981 movie (Thousand Pieces of Gold) made about her life. He called her Polly, but his name remains unknown (maybe Hong King).

Idaho would be Polly's home for the next 60 years.

Her first challenge would be to learn English. Being from Mandarin-speaking northern China, she could not even speak to the other Chinese, who mostly from the south spoke Cantonese or other dialects. All Chinese writing was mostly the same, but Polly couldn't write.

Later, she somehow managed to get away from her owner and ended up with local saloon keeper Charlie Bemis who had befriended her since she arrived. Polly ran his popular boarding house for him and was his housekeeper. Legend says Charlie won her in a poker game with her Chinese owner, but she always denied it.

In 1890, a sore loser in a poker game shot Charlie in the cheek. The doctor predicted he would die, but he survived after Polly cleaned his wound with a crochet hook and treated it with herbs, cutting the bullet out of his neck with a razor.

Four years later, Polly and Charlie married.

Because she was brought to America illegally, deportation remained a constant threat hanging over Polly's head - until she married Charlie.

Interracial marriages were against the law in those days in many states, but in Idaho, it only applied between Caucasians and African-Americans. In 1921, "Mongolians" was added to the prohibited list, but by then, Polly and Charlie had been married 27 years.

Polly had a happy personality, was petite, pretty, and witty - which made her popular with everyone. She learned western cooking, adopted Western ways, and loved children and animals.

She could also be tough. When one diner complained about the coffee, she pulled out a butcher's knife and challenged him to repeat his complaint. The coffee was just fine.

Polly and Charlie built a two-story homestead for themselves 17 miles from town in a deep canyon on the Salmon River - also called the River of No Return because it was only navigable in one direction.

Their neighbors were two German miners - Peter Klinkhammer and Charlie Shepp - who mined gold claims in the hills.

Polly and Charlie Bemis were quite different. Charlie was lazy, liked to play his fiddle and gamble, while the industrious Polly would tend the garden and orchard, take care of the cows, horses, cat, dog, chickens and pet cougar, crochet and sew, and preserve vegetables and fruit to sell. She also became an excellent fisherman, once catching 27 fish in one day.

For years she stayed home running the ranch, while Charlie would ride to town to sell their products and check on his saloon.

By 1919, Charlie was bedridden and Polly had to care for him. If she needed help, she'd hang a towel upon a bush and one of the Germans would rush over. Eventually, a battery-powered phone line replaced the towel.

When phonographs and radios were invented, Polly was enthralled. No longer were they living out in the wilderness in isolation. She loved listening to Cal Stewart's funny monologues. Her favorite was "Uncle Josh in a Chinese Laundry."

Because Polly was an interesting character with an interesting story, magazine articles began to appear about the unusual couple. Soon tourists would drop in to meet them and enjoy their hospitality. She would also take in miners who were ill or injured and nurse them back to health. She was becoming a legend.

An article in Field and Stream magazine by famed publisher Eleanor "Cissy" Patterson - written under her former married name Countess Eleanor Gizycka - described Polly as "neat as a pin, wrinkled as a walnut, and at 67 she is full of dash and charm."

By the 1920s, life was closing in on the aging couple: The house burned down and they moved across the river to stay with their German neighbors.

On Oct. 29, 1922, Charlie died of a lung ailment. Polly moved back to Warren, where childless herself, she took in six-year-old Gay Carrey so the girl could attend school in town.

Neighbor Pete Klinkhammer said the Bemises had "a marriage of convenience." Charlie needed Polly to take care of him, and Polly needed the marriage to prevent her from being deported back to China.

In the ensuing years after Charlie died, Polly's life opened up a bit. She took her first automobile ride, saw her first train, and watched her first movie in Grangeville. She also visited Boise, seeing her first streetcar, tall building, and rode in her first elevator.

In 1924, Polly Bemis returned to the canyon to live in a cabin Klinkhammer and Shepp built for her. In the summer of 1933, she fell ill and was taken to Grangeville, strapped to the back of a horse. She died of a stroke in a nursing home on Nov. 6.

She was buried in the Grangeville Cemetery.

In 1980, Polly was reburied on her beloved ranch; the cabin now restored and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At a time when the Chinese were being vilified in America, Polly Bemis stood out as a beacon of hope for future generations.

The diminutive peasant woman who was sold as a slave but eventually lived in freedom and became a giant personality in her remote little Idaho community made the "melting pot" work for her.

The Salmon was Polly's "river of no return." She never saw China again, but instead became a glittering chapter in the history of a growing multicultural America.

Syd Albright is a writer/journalist/biographer living in Post Falls. He is chairman of the Kootenai County Historic Preservation Commission.

===

Miscegenation laws in America ...

Laws prohibiting marriages between races were not repealed in the U.S. until 1959. Military authorities, in particular, labored under those laws during the World War II and Korean War conflicts when American military personnel sought to marry Asian women. Asian immigrants were not even allowed to become naturalized American citizens until 1943 - 10 years after Polly Bemis died.

===

'Uncle Josh in a Chinese Laundry ...'

Polly Bemis didn't have a problem with political correctness. She loved to listen to a recording of comedian Cal Stewart's character Uncle Josh brawling with a Chinese laundry owner who wouldn't give him his clothes without the claim ticket:

"In less 'n a minnit we wuz a rollin' round on the floor; fust I wuz on top, and then Mr. Hop Soon wuz on top, and you couldn't hav told which one of us the pig tail belonged to. We upset the stove and kicked out the winder, and I sot Mr. Hop Soon in the washtub, and when I got out of thar I had somebody's washin' in one hand and about five yards of that pig tail in tother, and Mr. Hop Soon, he wuz standin' thar yellin' - ung wa moo ye song ki le yung noy song oowe polecee, polecee, polecee.

I had quite a time with that heathen critter."

republished with permission from Syd Albright 8/14/2015

===============================================

Changes to her name are attributed to the latest biography about her by Dr. Priscilla Wegars, entitled "Polly Bemis: The Life and Times of a Chinese American Pioneer".

In 1987, Polly was exhumed in Grangeville and her remains were brought back to her Salmon River home.

Contributor: Lee Loo (50331449)

=====

Also, Dr. Wegars also mentions that Polly was not from Guangdong. She suspects she is from northern China, around the Inner Mongolia area.

The book references interviews where Polly says that she was from the north and brought out of China via Shanghai. She did not speak Cantonese when she arrived in the US, further proving her origin as outside of southern China.

Contributor: Lee Loo (50331449)