--------------------------

San Diego Reader

I Wasn't There to Hold the Candle, So I Don't Know

Why did Frank Bompensiero come west?

By Judith Moore, Feb. 18, 1999

Frank Bompensiero jumped off a freight train in San Diego in the early 1920s. He was 16 or 17 or perhaps even 18 years old. He was five feet, six inches tall. He had hazel eyes and light brown hair. He was in trouble. Big trouble.

Bompensiero’s parents, Giuseppe and Anna Maria Tagliavia, in 1904 had come to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from Porticello, a fishing village near Palermo in Sicily. (A quite elderly Sicilian-American told me, about Palermo, “You hear lots of bad things about people from Palermo, but good people also came from there.”) Frank, their first child, was born in 1905. Giuseppe, a laborer, never adjusted to Wisconsin’s cold. He frequently was ill. The Bompensieros sailed home to Porticello in 1915, taking Frank, his brother Sam, and two sisters.

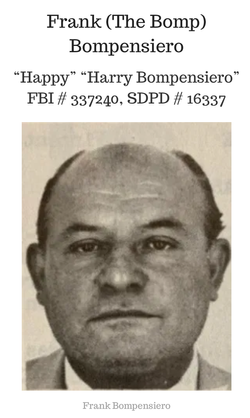

Mary Ann, Bompensiero’s only child (who was born in San Diego in 1931 and has lived here for most of her life), loaned me a photograph of Bompensiero that had been taken in a photographer’s studio in Sicily. She guesses the photograph must have been made in Palermo. She hypothesizes that the photograph was made as a keepsake for his mother. Mary Ann does not know how old her father was when this photograph was taken. He may have not yet been 16. He may have been 15. He wears a suit that appears to be gray, a white shirt whose collar seems to set right beneath his chin. He wears a dark tie. He sits with his legs crossed. He has slicked back his hair. He has not begun to take on the weight that he will take on in later years. His dress and his posture lend him the look of the ardent, hopeful emigrant, the boy who will come to America, who will make good. I stare into the eyes that stare out of the photograph. I can read nothing from his gaze. His gaze seems entirely neutral.

Frank returned to Milwaukee in 1921 or 1922 or even as late as 1923, without his family. No one can or will tell me why Bompensiero did not stay in Sicily. Perhaps the family needed the cash that Bompensiero could earn in the United States. Whole villages in southern Italy were being supported by Sicilians who’d come to the U.S. to work. Immigrants from Italy to the United States, during this era, were sending back as much as one million lire a year to Italian relatives. Or, perhaps Bompensiero wanted to get away from the village where, after ten years in Milwaukee, conditions must have seemed incredibly primitive. Donkeys and mules pulled wooden carts. The evil eye — occhio malo — was cast. Women regularly died in childbirth, and children, in infancy.

Mussolini was on his way to transforming all Italy, little Sicily included, into a single-party, totalitarian regime. A certain hopelessness might have infected Bompensiero in Porticello. If he stayed, all he could hope for, at best, was, eventually, to own his own fishing boat and to spend a lifetime hauling tuna out of the sea. Giuseppe and Anna Maria, when they left Milwaukee, had intended to return to America. Maybe the parents proposed that their eldest son return to ready a place for them, or to earn the money for the boat fare. Or, perhaps Bompensiero got himself into difficulty in Porticello or nearby Palermo, Sicily’s ancient capital, where Byzantine-influenced mosaics glittered in harsh sunlight and dour men dressed in dark suits hurried to appointments in shadowy rooms. Who knows?

The Milwaukee city directory between 1918 and 1922 lists a Salvatore Bompensiero, barber, as resident in Milwaukee’s Little Italy. Salvatore was Giuseppe’s brother. So it is possible to imagine that after the two-week passage from Porticello to Naples and from Naples to New York and the two-day train trip from New York to Milwaukee, that Bompensiero unloaded his cardboard suitcase at his uncle Salvatore’s house. The Milwaukee city directories for those years list names of many Porticello families. Any of the Guardalebenes, Busallachis, Catallanos, Tagliavias, Sanfilippos, San Filippis, Cravellos, Carinis, Aliotos, Balistrieris, might have unrolled a pallet for their young compare.

Mary Ann told me, “From what I understand, when Daddy was in Milwaukee, he was working with coal. I don’t know how true that is, but that’s what I understand.”

Bompensiero may have been “working with coal.” Certainly, many Sicilian immigrants—illiterate even in their own language and with only muscle to sell — went to work as manual laborers.

Bompensiero, in November, 1950, testified in Los Angeles before a closed session of the Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, popularly known as the Kefauver Committee.

Mr. Halley. Where were you born?

Mr. Bompensiero. Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Mr. Halley. In what business were you in Wisconsin?

Mr. Bompensiero. I was just working in a factory. A.O. Smith.

Mr. Halley. What kind of a plant is it?

Mr. Bompensiero. They make automobile parts.

Mr. Halley. And that was your only occupation until you came here?

Mr. Bompensiero. Yes, sir.

Bompensiero may well have been “just working in a factory.” But, clearly, he had ambitions beyond grinding out engine blocks for A.O. Smith. At some point after Bompensiero arrived in Milwaukee, he became involved with a gang who made themselves useful to liquor smugglers and bootleggers. According to an old friend of Bompensiero’s, Bompensiero, in Milwaukee, “was always out stealing, out bootlegging, out hijacking.” Bompensiero’s friend explained that Bompensiero and his gang hijacked trucks that carried illegal booze. The trucks drove down from Canada. The gang stopped the trucks and either emptied the contents of the trucks into its own vehicle or drove off with the truck and its contents. My informant did not know which. During one of these events, something went wrong and Bompensiero ended by shooting and killing one of the smugglers.

I tried to imagine Bompensiero, at this age. I hope that you will try to imagine this too. You’ve lived for five or six or seven years in a house with outdoor plumbing and no electricity. Your skills are a fisherman’s skills. You read and write English at a rudimentary level. You may not even understand English all that well when you hear it spoken by native Milwaukeeans. Your accent is regularly mimicked. And the “native” Milwaukeeans, people not more than one or two generations away from Germany and Ireland and Scandinavia and Russian and Eastern European shtetls, look down on you. They guffaw about how your people aren’t that far removed from the monkeys. In their newspapers and magazines cartoonists portray Italian men as sinister and evil, or, they draw them as comic — fat-bellied, hair slicked down with olive oil, an ornate mustache waxed upward at its ends. They sketch them as organ grinders, playing a barrel organ on corners and begging for passersby’s coins. They taunt you with “wop” and “spaghetti bender” and “guinea” and “goombah” and “greaseball.” They claim that you and your women are oversexed. They round up your men as suspects in sex crimes and murders. They accuse your men of Bolshevik leanings. They say they are bomb-tossers. They say they are “Black Hand” members who extort protection money from fellow immigrants. These natives warn their children against Italian and Sicilian children, claiming that they are carriers of lice, tuberculosis, typhoid, and physical and moral filth. In Massachusetts, in what all your people know is a put-up case, Sacco and Vanzetti have been sentenced to die in the electric chair. This, easily, you think, could happen to you. The hot seat.

--------------------------

San Diego Reader

I Wasn't There to Hold the Candle, So I Don't Know

Why did Frank Bompensiero come west?

By Judith Moore, Feb. 18, 1999

Frank Bompensiero jumped off a freight train in San Diego in the early 1920s. He was 16 or 17 or perhaps even 18 years old. He was five feet, six inches tall. He had hazel eyes and light brown hair. He was in trouble. Big trouble.

Bompensiero’s parents, Giuseppe and Anna Maria Tagliavia, in 1904 had come to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from Porticello, a fishing village near Palermo in Sicily. (A quite elderly Sicilian-American told me, about Palermo, “You hear lots of bad things about people from Palermo, but good people also came from there.”) Frank, their first child, was born in 1905. Giuseppe, a laborer, never adjusted to Wisconsin’s cold. He frequently was ill. The Bompensieros sailed home to Porticello in 1915, taking Frank, his brother Sam, and two sisters.

Mary Ann, Bompensiero’s only child (who was born in San Diego in 1931 and has lived here for most of her life), loaned me a photograph of Bompensiero that had been taken in a photographer’s studio in Sicily. She guesses the photograph must have been made in Palermo. She hypothesizes that the photograph was made as a keepsake for his mother. Mary Ann does not know how old her father was when this photograph was taken. He may have not yet been 16. He may have been 15. He wears a suit that appears to be gray, a white shirt whose collar seems to set right beneath his chin. He wears a dark tie. He sits with his legs crossed. He has slicked back his hair. He has not begun to take on the weight that he will take on in later years. His dress and his posture lend him the look of the ardent, hopeful emigrant, the boy who will come to America, who will make good. I stare into the eyes that stare out of the photograph. I can read nothing from his gaze. His gaze seems entirely neutral.

Frank returned to Milwaukee in 1921 or 1922 or even as late as 1923, without his family. No one can or will tell me why Bompensiero did not stay in Sicily. Perhaps the family needed the cash that Bompensiero could earn in the United States. Whole villages in southern Italy were being supported by Sicilians who’d come to the U.S. to work. Immigrants from Italy to the United States, during this era, were sending back as much as one million lire a year to Italian relatives. Or, perhaps Bompensiero wanted to get away from the village where, after ten years in Milwaukee, conditions must have seemed incredibly primitive. Donkeys and mules pulled wooden carts. The evil eye — occhio malo — was cast. Women regularly died in childbirth, and children, in infancy.

Mussolini was on his way to transforming all Italy, little Sicily included, into a single-party, totalitarian regime. A certain hopelessness might have infected Bompensiero in Porticello. If he stayed, all he could hope for, at best, was, eventually, to own his own fishing boat and to spend a lifetime hauling tuna out of the sea. Giuseppe and Anna Maria, when they left Milwaukee, had intended to return to America. Maybe the parents proposed that their eldest son return to ready a place for them, or to earn the money for the boat fare. Or, perhaps Bompensiero got himself into difficulty in Porticello or nearby Palermo, Sicily’s ancient capital, where Byzantine-influenced mosaics glittered in harsh sunlight and dour men dressed in dark suits hurried to appointments in shadowy rooms. Who knows?

The Milwaukee city directory between 1918 and 1922 lists a Salvatore Bompensiero, barber, as resident in Milwaukee’s Little Italy. Salvatore was Giuseppe’s brother. So it is possible to imagine that after the two-week passage from Porticello to Naples and from Naples to New York and the two-day train trip from New York to Milwaukee, that Bompensiero unloaded his cardboard suitcase at his uncle Salvatore’s house. The Milwaukee city directories for those years list names of many Porticello families. Any of the Guardalebenes, Busallachis, Catallanos, Tagliavias, Sanfilippos, San Filippis, Cravellos, Carinis, Aliotos, Balistrieris, might have unrolled a pallet for their young compare.

Mary Ann told me, “From what I understand, when Daddy was in Milwaukee, he was working with coal. I don’t know how true that is, but that’s what I understand.”

Bompensiero may have been “working with coal.” Certainly, many Sicilian immigrants—illiterate even in their own language and with only muscle to sell — went to work as manual laborers.

Bompensiero, in November, 1950, testified in Los Angeles before a closed session of the Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, popularly known as the Kefauver Committee.

Mr. Halley. Where were you born?

Mr. Bompensiero. Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Mr. Halley. In what business were you in Wisconsin?

Mr. Bompensiero. I was just working in a factory. A.O. Smith.

Mr. Halley. What kind of a plant is it?

Mr. Bompensiero. They make automobile parts.

Mr. Halley. And that was your only occupation until you came here?

Mr. Bompensiero. Yes, sir.

Bompensiero may well have been “just working in a factory.” But, clearly, he had ambitions beyond grinding out engine blocks for A.O. Smith. At some point after Bompensiero arrived in Milwaukee, he became involved with a gang who made themselves useful to liquor smugglers and bootleggers. According to an old friend of Bompensiero’s, Bompensiero, in Milwaukee, “was always out stealing, out bootlegging, out hijacking.” Bompensiero’s friend explained that Bompensiero and his gang hijacked trucks that carried illegal booze. The trucks drove down from Canada. The gang stopped the trucks and either emptied the contents of the trucks into its own vehicle or drove off with the truck and its contents. My informant did not know which. During one of these events, something went wrong and Bompensiero ended by shooting and killing one of the smugglers.

I tried to imagine Bompensiero, at this age. I hope that you will try to imagine this too. You’ve lived for five or six or seven years in a house with outdoor plumbing and no electricity. Your skills are a fisherman’s skills. You read and write English at a rudimentary level. You may not even understand English all that well when you hear it spoken by native Milwaukeeans. Your accent is regularly mimicked. And the “native” Milwaukeeans, people not more than one or two generations away from Germany and Ireland and Scandinavia and Russian and Eastern European shtetls, look down on you. They guffaw about how your people aren’t that far removed from the monkeys. In their newspapers and magazines cartoonists portray Italian men as sinister and evil, or, they draw them as comic — fat-bellied, hair slicked down with olive oil, an ornate mustache waxed upward at its ends. They sketch them as organ grinders, playing a barrel organ on corners and begging for passersby’s coins. They taunt you with “wop” and “spaghetti bender” and “guinea” and “goombah” and “greaseball.” They claim that you and your women are oversexed. They round up your men as suspects in sex crimes and murders. They accuse your men of Bolshevik leanings. They say they are bomb-tossers. They say they are “Black Hand” members who extort protection money from fellow immigrants. These natives warn their children against Italian and Sicilian children, claiming that they are carriers of lice, tuberculosis, typhoid, and physical and moral filth. In Massachusetts, in what all your people know is a put-up case, Sacco and Vanzetti have been sentenced to die in the electric chair. This, easily, you think, could happen to you. The hot seat.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement