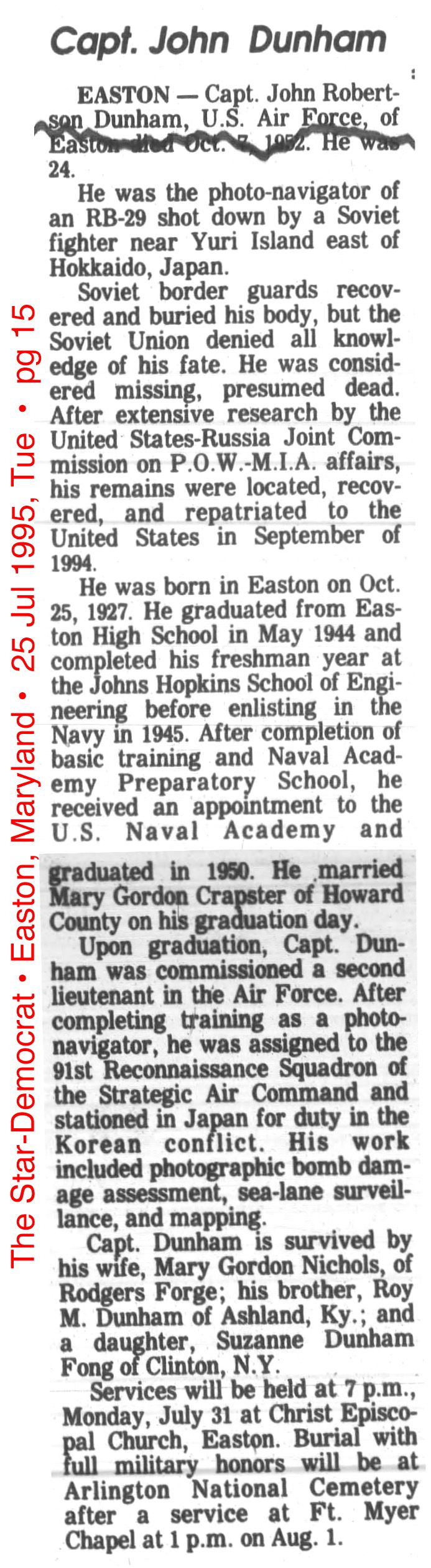

Killed on 7 October 1952, after a Soviet fighter plane shot down his RB-29 photo-reconnaissance plane in the Kuril Islands near Hokkaido Island.

28 May 1949 - 6 October 1952

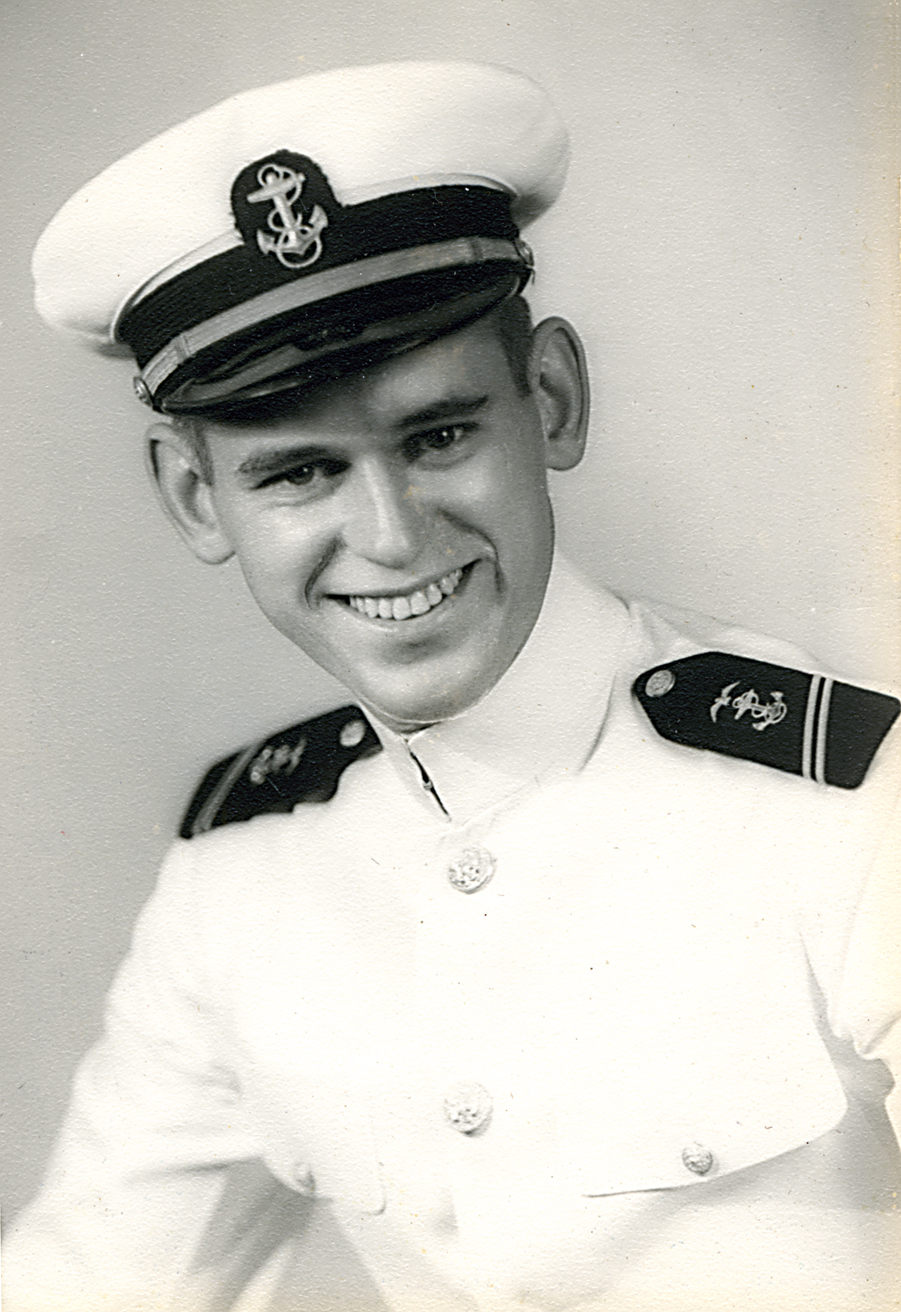

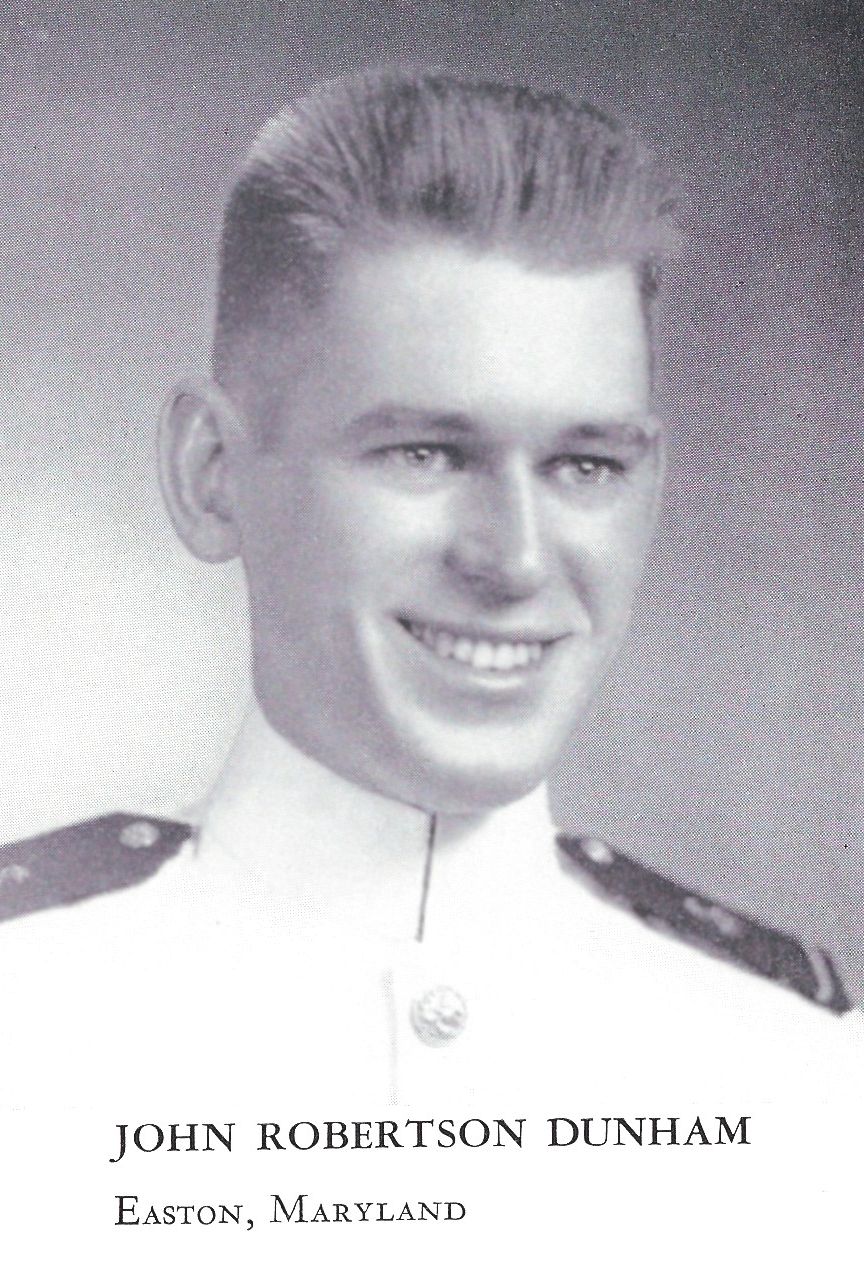

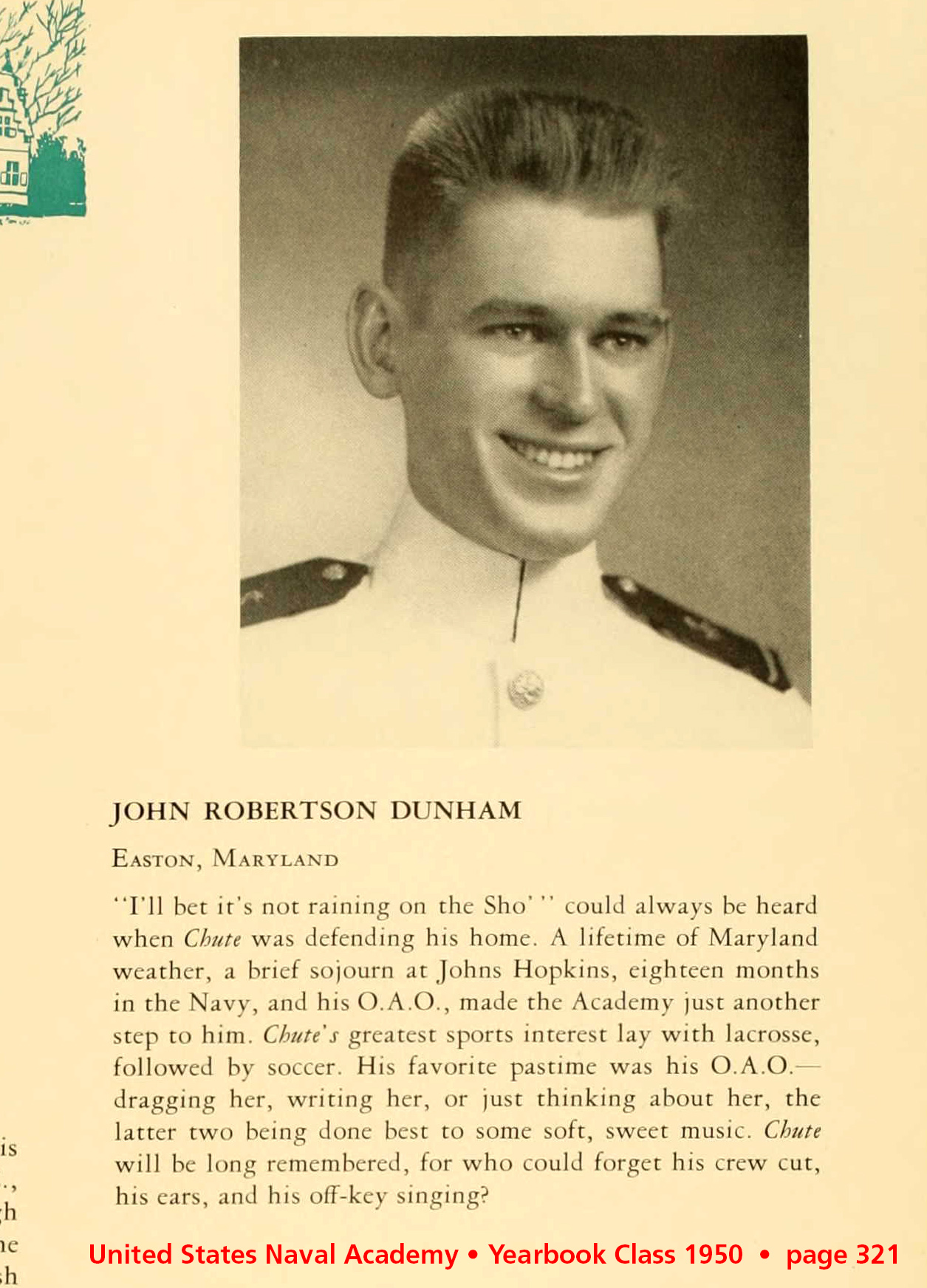

Dressed in an organdy-white gown, her blond hair gleaming, Mary Gordon Crapster watched as her fiancé, John Robertson Dunham, removed his class ring from a small box. The date was 28 May 1949, and the occasion was the Midshipman's Ring Dance at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD. With a big grin, John placed a blue ribbon through the ring and hung it around Mary's neck. She would wear the ring until a special ceremony during the dance. Then Mary would slip it onto John's right hand - where it was to remain for the rest of his life. This was one of the Naval Academy's proudest traditions.

Mary and John had known each other since they were 17. She was charmed by this tall man with friendly brown eyes who was known to everyone as "Chute." He had earned the nickname because of the way he pronounced "choo-choo" as a child.

In June 1950, on the day Chute graduated, he and Mary were married at the Naval Academy chapel. In those days, before the Air Force Academy was established, one-quarter of Annapolis graduates each year were given the option of joining the Air Force. Chute volunteered and began training as a navigator for aerial reconnaissance.

Mary and Chute said good-bye to each other in May 1952, when he was about to be shipped out to Japan with his air-reconnaissance unit. Their first child was due in three months. Smiling and patting Mary's stomach, Chute promised he would see them both at Thanksgiving.

Then, during a Red Cross telephone call in August 1952 when their baby was a week old, Mary and Chute were giddy in their joy over Suzanne's birth. She was the affirmation of their love and dreams of a long and happy life together. Even though they wrote almost every day, that one rare phone call was the only time they talked after their daughter's birth. They never spoke again.

7 October 1952

On 7 October 1952, the world was focused on the Korean War and Captain John Dunham was serving as Navigator on the ‘Sunbonnet King,' a U.S. RB-29 Superfortress photo-reconnaissance plane assigned to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing. The eight American airmen aboard the reconnaissance plane had been photo-mapping several miles from one of the War's most hotly disputed zones - the Kuril Islands between Japan and the Soviet Union.

Suddenly, bright tracer bullets spat across the cold blue sky and slammed into the left wing of the Sunbonnet King. Moments later a second Soviet fighter sent a volley into the plane's tail, blasting it away. Emitting flames and black smoke, the crippled aircraft nosed hard left and began a downward spiral. Four miles below, Vasily Saiko, a 24-year-old sergeant in the Soviet Maritime Border Guards, stood on the deck of his patrol vessel, watching the grim ballet above. Seconds later the Sunbonnet King crashed and exploded in Soviet waters near the tiny Japanese island of Yuri.

Saiko and the two other Soviet sailors were ordered to take a small boat and begin collecting what debris they could find. The waves were choppy, and from their vantage point little was visible except gas and oil floating on the surface and a rubber tire bobbing aimlessly amid the flotsam. Suddenly the men spotted a partially submerged parachute. Attached to its cords was a man floating face down in the oily, dark waters. 'He might be alive!' Saiko shouted. The three sailors managed to pull the American into the boat only to make a gruesome discovery: the front and top of the airman's head had been sheared off, leaving no vestige of a face. The men grimaced and looked away. Solemnly they returned to the patrol vessel, where the American's body was wrapped in a tarpaulin and stowed.

The next day Saiko was instructed to escort the body to Yuri Island and wait until it was picked up for examination and burial. At the docking point, alone with the body, Saiko wondered about the American. He was someone's son - perhaps a husband, even a father. This man has people who love him, Saiko thought.

On impulse Saiko pulled the tarp away. On the man's right hand was the most extraordinary ring he had ever seen. Large and heavy, it seemed to be made of the purest gold. Slipping the ring from the man's finger, Saiko furtively studied the engraving inside. A name, he supposed, but the Roman letters were strange to his eye. Saiko then dropped the ring into his pocket. I could go to prison for this, he thought. Some Soviet naval officer or KGB agent would surely think such a treasure should be his own. Saiko assured himself that, if necessary, he could flip the ring into the sea.

Soon a burial detail arrived to take the body. Saiko watched as the men placed the American's body on a litter. Then, as Saiko's boat shoved off from the dock, they were lost in the fog. Saiko slipped a hand deep into his pocket and rolled the heavy ring between his fingers.

Of course, Mary Dunham knew none of that. The Soviet Union denied any knowledge of the plane's fate. Mary says she struggled for her sanity. "I didn't know if I was a wife or a widow," she said. "I didn't know what to do or where to go. I thought he could be a Soviet prisoner, being tortured. It was agony." In 1955, the U.S. government said her husband was presumed dead. But it was another decade before she married again.

Back at Home

Suzanne, the daughter who resembles the father she never saw, graduated from Wellesley College and from law school.

Meanwhile, the Russian sailor, Vasily Saiko, held on to the ring for decades. Late in 1993, Vasily saw a TV commercial that startled him. This was after the Soviet Union had disintegrated and Russian President Boris Yeltsin promised to help find out about missing Americans. The Joint Commission on POW-MIA Affairs was asking Russians with information to come forward. Vasily's wife, Lyuba, told her husband the time had come. He took a 24-hour train journey to Moscow, and presented the ring to the Commission. Engraved inside was "John Robertson Dunham."

On 7 December 1993, Mary received a phone call with the news. A few weeks later at a Pentagon ceremony, she received John's ring. But what of his remains? Of the eight crew members on the U.S. spy plane, Dunham's body was the only one recovered. Saiko said he was buried on the islet of Yuri, and searchers found the grave on 2 September 1994. DNA tests confirmed the identity.

1 August 1995 – Arlington National Cemetery

The funeral had the full panoply of a procession from the Fort Myer Chapel to the gravesite behind an Air Force band and honor guard and six black horses pulling the flag-draped coffin on a caisson.

A giant B-52 bomber swept overhead in salute. Three rifle volleys crackled across the silence of the sun-drenched cemetery of warriors. A bugler sounded Taps. Captain John Robertson Dunham was buried at last in his native soil and with full military honors.

The funeral in Arlington National Cemetery before more than 200 relatives, Naval Academy classmates, friends and well-wishers contrasted sharply with the Air Force officer's first funeral, a lonely affair in October 1952 on remote Yuri, a wind-swept islet in the Russian-occupied Kurils, north of Japan. He was buried then -- with respect, according to reports -- by Russian border guards who had pulled his body from the icy Pacific near Hokkaido Island.

"This brings us to closure," said John's older brother, Roy Dunham, 70, of Ashland, KY. He was the last relative to see John Dunham alive, in Japan just weeks before the fateful flight. "The days we spent together hold memories," said Mr. Dunham, who had been hospitalized in Japan and who learned on the day his hospital ship reached San Francisco that John's plane was missing.

Roy Dunham sat near his brother's widow, Mary Dunham Nichols, 69, of Rodgers Forge. He was best man at John and Mary's wedding at the Academy Chapel in June 1950, just hours after John Dunham's graduation from the Naval Academy. The Korean War began exactly three weeks later.

"It's closure. It's a great sigh of relief to know that he's buried, to have it completed," Mary Nichols said after the ceremony. She wore her dead husband's Academy class ring on a double gold chain around her neck.

"It's hard to say how I feel," said Suzanne Dunham Fong, who was 6 weeks old when her father's plane was shot down. At the memorial service at the Dunham family church in Easton, and again the following day, Mrs. Fong said she touched her father's coffin, as did her sons, Jonathan, 13, and Colin, 5, Captain Dunham's grandsons. "I told them that he had died for his country and they should be proud of him," she said. "My older son has cried a lot about this; the younger one is more interested in the airplanes. It was important for them to touch the coffin." The smooth wood was her first physical contact with the father she never knew, Suzanne said. "I just had to. I feel whole for the first time. It feels good to know where he is."

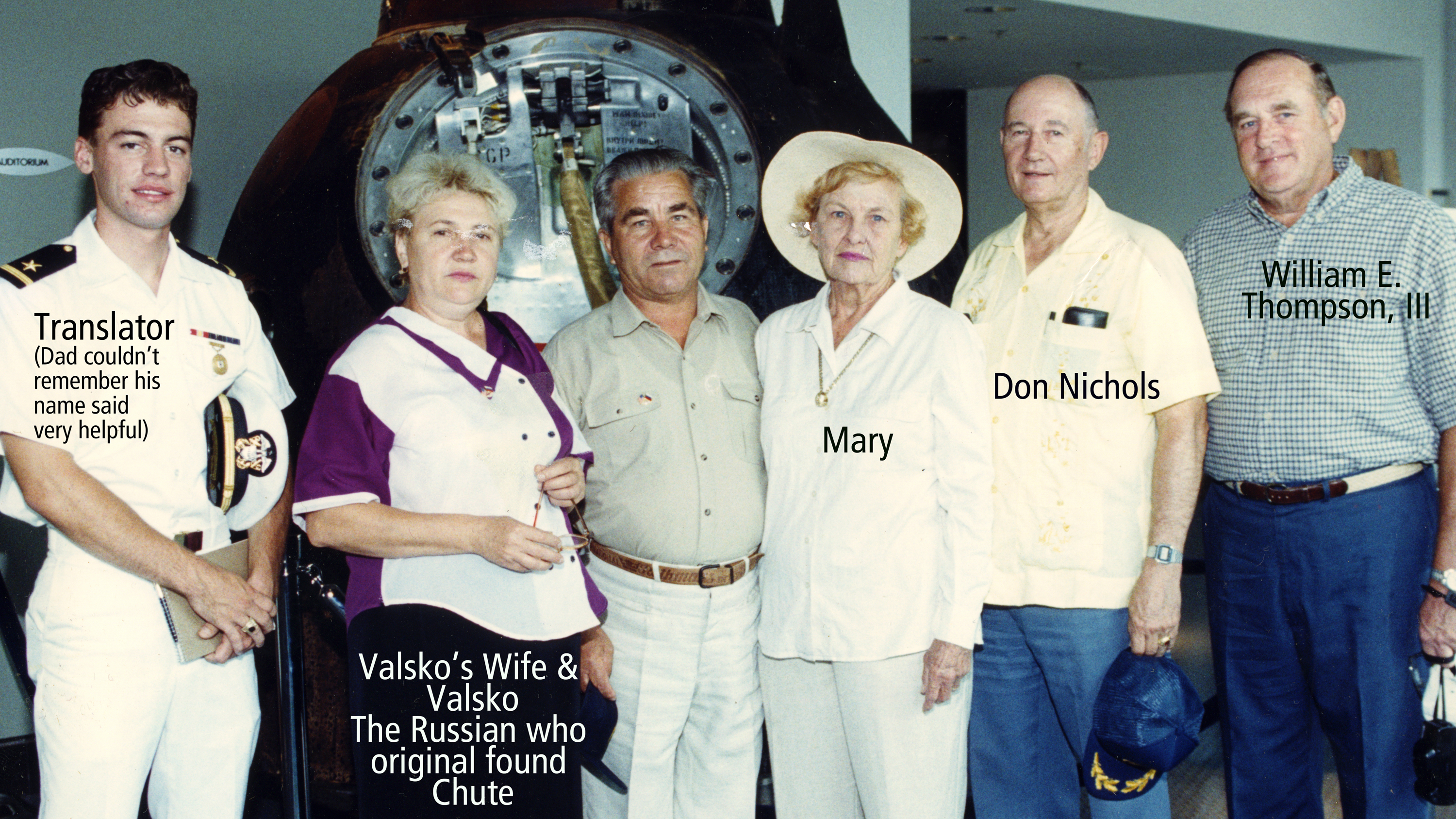

Vasily Saiko, 66, the former Russian border guard sailor who kept the ring after pulling Captain Dunham from the water, was at the funeral with his wife, Luba, as a guest of the family. "I kept it as a memory of the event and I thought I would give it back one day," he said through an interpreter.

"Mr. Saiko was the linchpin that allowed my dad to come home. We never thought we'd ever see this and without him we wouldn't have," Suzanne Fong said.

"It was a sad ceremony, but I'm happy that he finally rests in his native land," said Mr. Saiko, a short, stocky man with iron-gray hair who said he was a riverboat captain after leaving the border guards. "The main difference is that the political situation was real bad between our two countries then and is not now."

Another hero is finally at rest, at home.

A personal note about John Dunham from Jack Davison, USNA Class of 1953:

"During the fall of 1949, at the start of my plebe year and Chute Dunham's last at the Academy, I made the mistake of showing how clever I was, in a way that reflected unfavorably on a classmate who did not know the answer to a question, that I did. Mr Dunham "invited" me to "come around" to his room, where he apprised me forcefully of my error in "bilging" a classmate. (A ship is "bilged" when it is damaged below the waterline by gunfire in battle, or by collision with a submerged object like a rock, so that it is in sinking condition; the meaning in this context should be obvious.) He directed me into his closet to perform 53 pushups, my class number, to make the lesson stick in my memory. I have never "bilged" a classmate or other friend since that day. Chute Dunham was an important figure in my formation."

Honors

Capt John R. Dunham has Honoree Record 10518 at MilitaryHallofHonor.com.

Bio compiled by Charles A. Lewis

Killed on 7 October 1952, after a Soviet fighter plane shot down his RB-29 photo-reconnaissance plane in the Kuril Islands near Hokkaido Island.

28 May 1949 - 6 October 1952

Dressed in an organdy-white gown, her blond hair gleaming, Mary Gordon Crapster watched as her fiancé, John Robertson Dunham, removed his class ring from a small box. The date was 28 May 1949, and the occasion was the Midshipman's Ring Dance at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD. With a big grin, John placed a blue ribbon through the ring and hung it around Mary's neck. She would wear the ring until a special ceremony during the dance. Then Mary would slip it onto John's right hand - where it was to remain for the rest of his life. This was one of the Naval Academy's proudest traditions.

Mary and John had known each other since they were 17. She was charmed by this tall man with friendly brown eyes who was known to everyone as "Chute." He had earned the nickname because of the way he pronounced "choo-choo" as a child.

In June 1950, on the day Chute graduated, he and Mary were married at the Naval Academy chapel. In those days, before the Air Force Academy was established, one-quarter of Annapolis graduates each year were given the option of joining the Air Force. Chute volunteered and began training as a navigator for aerial reconnaissance.

Mary and Chute said good-bye to each other in May 1952, when he was about to be shipped out to Japan with his air-reconnaissance unit. Their first child was due in three months. Smiling and patting Mary's stomach, Chute promised he would see them both at Thanksgiving.

Then, during a Red Cross telephone call in August 1952 when their baby was a week old, Mary and Chute were giddy in their joy over Suzanne's birth. She was the affirmation of their love and dreams of a long and happy life together. Even though they wrote almost every day, that one rare phone call was the only time they talked after their daughter's birth. They never spoke again.

7 October 1952

On 7 October 1952, the world was focused on the Korean War and Captain John Dunham was serving as Navigator on the ‘Sunbonnet King,' a U.S. RB-29 Superfortress photo-reconnaissance plane assigned to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing. The eight American airmen aboard the reconnaissance plane had been photo-mapping several miles from one of the War's most hotly disputed zones - the Kuril Islands between Japan and the Soviet Union.

Suddenly, bright tracer bullets spat across the cold blue sky and slammed into the left wing of the Sunbonnet King. Moments later a second Soviet fighter sent a volley into the plane's tail, blasting it away. Emitting flames and black smoke, the crippled aircraft nosed hard left and began a downward spiral. Four miles below, Vasily Saiko, a 24-year-old sergeant in the Soviet Maritime Border Guards, stood on the deck of his patrol vessel, watching the grim ballet above. Seconds later the Sunbonnet King crashed and exploded in Soviet waters near the tiny Japanese island of Yuri.

Saiko and the two other Soviet sailors were ordered to take a small boat and begin collecting what debris they could find. The waves were choppy, and from their vantage point little was visible except gas and oil floating on the surface and a rubber tire bobbing aimlessly amid the flotsam. Suddenly the men spotted a partially submerged parachute. Attached to its cords was a man floating face down in the oily, dark waters. 'He might be alive!' Saiko shouted. The three sailors managed to pull the American into the boat only to make a gruesome discovery: the front and top of the airman's head had been sheared off, leaving no vestige of a face. The men grimaced and looked away. Solemnly they returned to the patrol vessel, where the American's body was wrapped in a tarpaulin and stowed.

The next day Saiko was instructed to escort the body to Yuri Island and wait until it was picked up for examination and burial. At the docking point, alone with the body, Saiko wondered about the American. He was someone's son - perhaps a husband, even a father. This man has people who love him, Saiko thought.

On impulse Saiko pulled the tarp away. On the man's right hand was the most extraordinary ring he had ever seen. Large and heavy, it seemed to be made of the purest gold. Slipping the ring from the man's finger, Saiko furtively studied the engraving inside. A name, he supposed, but the Roman letters were strange to his eye. Saiko then dropped the ring into his pocket. I could go to prison for this, he thought. Some Soviet naval officer or KGB agent would surely think such a treasure should be his own. Saiko assured himself that, if necessary, he could flip the ring into the sea.

Soon a burial detail arrived to take the body. Saiko watched as the men placed the American's body on a litter. Then, as Saiko's boat shoved off from the dock, they were lost in the fog. Saiko slipped a hand deep into his pocket and rolled the heavy ring between his fingers.

Of course, Mary Dunham knew none of that. The Soviet Union denied any knowledge of the plane's fate. Mary says she struggled for her sanity. "I didn't know if I was a wife or a widow," she said. "I didn't know what to do or where to go. I thought he could be a Soviet prisoner, being tortured. It was agony." In 1955, the U.S. government said her husband was presumed dead. But it was another decade before she married again.

Back at Home

Suzanne, the daughter who resembles the father she never saw, graduated from Wellesley College and from law school.

Meanwhile, the Russian sailor, Vasily Saiko, held on to the ring for decades. Late in 1993, Vasily saw a TV commercial that startled him. This was after the Soviet Union had disintegrated and Russian President Boris Yeltsin promised to help find out about missing Americans. The Joint Commission on POW-MIA Affairs was asking Russians with information to come forward. Vasily's wife, Lyuba, told her husband the time had come. He took a 24-hour train journey to Moscow, and presented the ring to the Commission. Engraved inside was "John Robertson Dunham."

On 7 December 1993, Mary received a phone call with the news. A few weeks later at a Pentagon ceremony, she received John's ring. But what of his remains? Of the eight crew members on the U.S. spy plane, Dunham's body was the only one recovered. Saiko said he was buried on the islet of Yuri, and searchers found the grave on 2 September 1994. DNA tests confirmed the identity.

1 August 1995 – Arlington National Cemetery

The funeral had the full panoply of a procession from the Fort Myer Chapel to the gravesite behind an Air Force band and honor guard and six black horses pulling the flag-draped coffin on a caisson.

A giant B-52 bomber swept overhead in salute. Three rifle volleys crackled across the silence of the sun-drenched cemetery of warriors. A bugler sounded Taps. Captain John Robertson Dunham was buried at last in his native soil and with full military honors.

The funeral in Arlington National Cemetery before more than 200 relatives, Naval Academy classmates, friends and well-wishers contrasted sharply with the Air Force officer's first funeral, a lonely affair in October 1952 on remote Yuri, a wind-swept islet in the Russian-occupied Kurils, north of Japan. He was buried then -- with respect, according to reports -- by Russian border guards who had pulled his body from the icy Pacific near Hokkaido Island.

"This brings us to closure," said John's older brother, Roy Dunham, 70, of Ashland, KY. He was the last relative to see John Dunham alive, in Japan just weeks before the fateful flight. "The days we spent together hold memories," said Mr. Dunham, who had been hospitalized in Japan and who learned on the day his hospital ship reached San Francisco that John's plane was missing.

Roy Dunham sat near his brother's widow, Mary Dunham Nichols, 69, of Rodgers Forge. He was best man at John and Mary's wedding at the Academy Chapel in June 1950, just hours after John Dunham's graduation from the Naval Academy. The Korean War began exactly three weeks later.

"It's closure. It's a great sigh of relief to know that he's buried, to have it completed," Mary Nichols said after the ceremony. She wore her dead husband's Academy class ring on a double gold chain around her neck.

"It's hard to say how I feel," said Suzanne Dunham Fong, who was 6 weeks old when her father's plane was shot down. At the memorial service at the Dunham family church in Easton, and again the following day, Mrs. Fong said she touched her father's coffin, as did her sons, Jonathan, 13, and Colin, 5, Captain Dunham's grandsons. "I told them that he had died for his country and they should be proud of him," she said. "My older son has cried a lot about this; the younger one is more interested in the airplanes. It was important for them to touch the coffin." The smooth wood was her first physical contact with the father she never knew, Suzanne said. "I just had to. I feel whole for the first time. It feels good to know where he is."

Vasily Saiko, 66, the former Russian border guard sailor who kept the ring after pulling Captain Dunham from the water, was at the funeral with his wife, Luba, as a guest of the family. "I kept it as a memory of the event and I thought I would give it back one day," he said through an interpreter.

"Mr. Saiko was the linchpin that allowed my dad to come home. We never thought we'd ever see this and without him we wouldn't have," Suzanne Fong said.

"It was a sad ceremony, but I'm happy that he finally rests in his native land," said Mr. Saiko, a short, stocky man with iron-gray hair who said he was a riverboat captain after leaving the border guards. "The main difference is that the political situation was real bad between our two countries then and is not now."

Another hero is finally at rest, at home.

A personal note about John Dunham from Jack Davison, USNA Class of 1953:

"During the fall of 1949, at the start of my plebe year and Chute Dunham's last at the Academy, I made the mistake of showing how clever I was, in a way that reflected unfavorably on a classmate who did not know the answer to a question, that I did. Mr Dunham "invited" me to "come around" to his room, where he apprised me forcefully of my error in "bilging" a classmate. (A ship is "bilged" when it is damaged below the waterline by gunfire in battle, or by collision with a submerged object like a rock, so that it is in sinking condition; the meaning in this context should be obvious.) He directed me into his closet to perform 53 pushups, my class number, to make the lesson stick in my memory. I have never "bilged" a classmate or other friend since that day. Chute Dunham was an important figure in my formation."

Honors

Capt John R. Dunham has Honoree Record 10518 at MilitaryHallofHonor.com.

Bio compiled by Charles A. Lewis